Hidden Hazards – Donald Grant

My introduction to life as a lay-missionary teacher at Wirui Mission station, Wewak, on the North Coast of PNG, could not have been more unique. Dutifully, on the morning of 28 January 1959, I fronted up before the desk of Fr Peter O’Reilly, the Director of Catholic Education for the Diocese. Fr Pete didn’t muck around. ‘There are no classes this week, Don. But I’d like you to go down to the workshop area and supervise some workers digging out an unexploded bomb.’

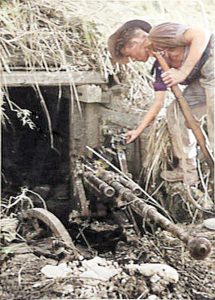

Remains of both Japanese and American planes in the form of broken sections of fuselages, wings and cockpits

My God, I thought, what have I gotten myself into? Well, I guess that’s part of the life around here, so I suppose I have to go. No one in the office had batted an eyelid at Fr Pete’s request; so off I went to the workshop area.

Sure enough, there it was, a 500-pound bomb, wrapped in rope, being hoisted out of a large hole by five or six men who carefully laid it by the side of the road to await collection by the mission truck. On completion of that task, I breathed a sigh of relief then gratefully retired from the scene. I had been told some bombs had a detonator located at the rear section so, when I observed one of the rear tailfins ‘swaying in the breeze’, I wasn’t at all happy.

Later that week I wrote home and gave Mum and Dad an account of my introduction to life in PNG. Dad, a WWI veteran, hastily wrote back: Don’t go near unexploded bombs. Rope off the area and call in the army’s bomb disposal unit. If poor Dad had seen the mission truck duly arrive to load the bomb on board to take it to be dumped into the ocean, he would have had a heart attack.

Wewak was subjected to heavy land and sea warfare during the Second World War. In fact, the final surrender of Japanese troops engaged in PNG conflict took place at Moem beach, only eight kilometres from the town centre. The rusting remains of Jap trucks, ammo boxes and other items were still to be found scattered throughout the lush vegetation.

My mission station of Dagua, on the west coast of Wewak, still sported the remains of both Japanese and American planes in the form of broken sections of fuselages, wings and cockpits (pictured above). The station was actually built on a former Japanese airstrip, which explained why it was so difficult to grow garden vegetables successfully. The sandy soil had been saturated with oil to give it some strength and cohesion, making it safer, of course, for the coming and going of aircraft.

While I was at Dagua the army bomb-disposal team arrived unannounced to ‘remove’ several unexploded bombs, which they did by blowing two of them up. The explosions were literally house shaking, a couple of the teachers’ houses suffering broken windows. I suffered from shock myself, in as much as I had no idea that bombs could make such a deafening noise. I could only feel much sympathy for the poor people of European cities who had been subjected to the cruelty of saturation bombing, such as took place in London and Dresden.

Unfortunately, many locals lost their fear of unexploded bombs, etc. Along the coastal villages, it was not uncommon for enterprising fishermen to set to with hacksaws to retrieve the TNT, so as to fashion hand-bombs of some kind with which to blow up shoals of fish. As a consequence, I’ve met a couple of one-handed fishermen—the result of this practice.

It was also not that uncommon to come across old army ordinance on the mission station grounds; cleaning areas for gardening was hazardous. I remember one Saturday afternoon the Sisters setting fire to an area they wished to use as a garden. They got a marvellous fireworks display as unexploded bullets and smaller ordinance provided us all with an exciting afternoon’s entertainment.

One experience still comes vividly to mind. I was at Sunday dinner in our communal dining room when, from somewhere to the east of our station, came a huge explosion; almost immediately most of the mission personnel sprang to their feet and took off, scrambling into the various mission vehicles parked nearby. Only two of us remained sitting opposite each other at the long table adorned with the remnants of half-eaten meals. I, for one, had no desire to see the remains of blown-up bodies. Neither did the other guy.

But curiosity, not valour, won out. I had use of an old wartime Jeep, so Rod and I set off. By some unfortunate timing I happened to be the first to pull up at the mouth of the bush track leading to the site of the blast. With foreboding the two of us began walking into the unknown, my imagination running riot with images of mutilated bodies.

Then staggering towards us came an obviously dazed fellow, one hand holding his bloodied forehead. A quick examination revealed a gash to the bone; serious, but by no means life-threatening. ‘Anybody else in there?’ I demanded. ‘Yes,’ he replied.

Rod and I took off. A three-minute walk brought us to a clearing where two other bewildered men were sitting on the ground completely shocked and dazed but, thank God, physically uninjured. They had been extremely lucky. Unwittingly, they had set their fire on top of a hidden anti-personnel mine. Fortunately, they had been squatting around the fire when the mine exploded so the main force of the blast went up over their heads. That they were lucky was testified to by a nearby tree about the diameter of a man’s leg being snapped like a twig; anyone standing would have been decapitated.

A somewhat humorous sideline to this saga occurred after I had bundled the injured fellow into my Jeep to take him to hospital. Two old-time missionary priests appeared each with Holy Oils poised for use to administer the Last Rites. However, one was a canon lawyer, so the two debated with each other as to whether this poor suffering victim was seriously injured enough to receive Extreme Unction. Finally, the decision was reached, the Sacrament was administered and I was able to get the guy to the doctor. The Church has moved on since those days.

My fear of unexploded bombs was not alleviated when I boarded a government trawler that happened to be travelling to Kairiru Island, a journey which should have taken one and a half hours. To give sufficient space for carrying cargo, the passenger seating ran the length of the boat on each side leaving the centre free. I settled down on one side, but it was not long before I spotted an unexploded bomb under the passenger seat on the opposite side; it was being taken out to sea to be heaved overboard. To add to my concern, the vessel’s engine broke down when we were half an hour out of port, so we began drifting with the current, getting nowhere. Thank goodness the crew decided it was time to dispense with the bomb. Three of them duly lifted it up and allowed it to drop into the ocean, obviously counting that the damned thing would not blow us all up when it hit the water.

Kairiru Island, off the coast of Wewak, boasted a minor seminary. The boss, Fr Kalisz, saw the need for a sports field for the active young men who resided and studied at that establishment. Having obtained a small bulldozer he set about levelling an area of ground that bordered the seashore. As he drove back and forth on the job one afternoon, he suddenly found himself bouncing up and down as he proceeded to level a strip of ground about thirty metres in length. Much to his horror, on investigation, he began uncovering a row of drums packed with some type of explosive material, remnants of the Japanese effort to blow up any invading troops as they stormed the island.

The bomb-disposal squad missed one bomb when they came to Dagua Station. Having wandered down to the seashore at very low tide on a balmy afternoon, there before me, a bomb, the water gently lapping around it as it lay peacefully ten metres offshore; another reminder of hidden hazards.

I suppose many such hazards still lie hidden in remote locations in PNG. What with warfare taking place at present between various countries in our wounded world, it seems that hidden hazards will be with us for some time to come.