Matapui Part 1: EKKE BEINSSEN

It is late July 1929. A leaden heat, saturated with moisture, broods over Salamaua, the harbour town of the goldfields of New Guinea. I am waiting on the verandah of the only guesthouse. Like all the houses and storage sheds of the little white settlement, it stands on a coral reef perhaps a hundred metres in width, which connects the mainland to a steep island. I am waiting for my two future comrades.

Lump, my large, but not quite pure Irish Wolfhound, is lying at my feet with his tongue hanging out, pumping air. He is squinting obliquely at me with the whites of his eyes showing, as though he holds me responsible for the heat.

‘It was more pleasant up in the mountains, wasn’t it Lump?’ His squint turns into a broad grin, and he wags his stumpy tail, though his good manners don’t go as far as pulling his tongue in.

‘Cheer up, Lump, in a few days we will be going into the interior again. There you can hunt wild pigs, cassowaries, and kangaroos, guard the camp and take a bath in a cold mountain creek.’ In response he blinks his eyes and once again wags his stumpy tail as though he were saying: ‘I don’t quite understand what you are saying but I can see that you are happy, so I’ll consider it my duty to show a bit of pleasure too.’

‘Yes, this time I won’t have to depend solely on your company and that of a few natives,’ I say, and I get out the telegram and read it once again: Arriving with geologist by schooner Namanula. Will employ you and your twenty-five boys for a gold prospecting expedition on behalf of a German Rabaul-based syndicate. Regards Soltwedel.

Their boat is due today, and while I wait, I reminisce about my last two years in New Guinea. First, there were months of sailing various routes along the coast in a small trading schooner, carting copra from plantations to the depot in Rabaul. White breakers foaming over the coral reefs and playing along the shores of the islands; dark, green jungle, often reaching right down to the ocean; the fight for life and boat in the storms of the south-east and north-west monsoons; then again, nights floating along on a calm sea in chaste moon-lit silence.

Times when one developed an intimacy with the ocean; times of forgetting everything and dreaming without a care in the world.

We earn money, buy land, recruit workers, and start our own plantation. I work on the land with a few local men. They call me Master. I am their master, must fill this role and force myself to rule. They are like children, full of pranks, with a natural playfulness and usually also a good deal of naivety that wins me over. I spend months alone with them in the ocean-lapped jungle, while my Australian partner works the schooner, trading and carrying cargo. All our income goes into setting up this new plantation.

Then one dark night our sailing boat runs aground on a reef and breaks up.

Other disappointments follow in short succession. We have to abandon our plantation, and our partnership ends. But there are new challenges ahead. I take on work loading copra onto ocean-going ships in Rabaul. It’s not what I would choose to do but there is no choice.

Other casual jobs follow, often exhausting; work that whites are not accustomed to in the steamy tropical heat. Kanakas dripping with sweat; monotonous chants; French, Australian, British, and American sailors and engineers; hard-drinking captains with their rowdy humour; gold diggers, planters, traders and recruiters; wild nights of drinking. All the frenzy of the South Seas.

But this state of unthinking surrender to the moment could only be temporary. To reach my goals I must stay alert. Thus, it happens that one day I met Helmuth Baum, known by white and black alike simply as Boom. He is the embodiment of a New Guinea bushman—like a cassowary here one day and there the next, always walking barefoot and with little baggage, often for weeks on end, eating only sweet potatoes and bananas, but always with his toothbrush, soap, and razor in his haversack for use twice a day.

Boom had just returned from one of his long expeditions into the interior of the main island of New Guinea. His experiences fascinated me and his reports of discovering gold prompted me to make new plans. As he talked, night after night about the possibilities and probabilities of finding treasures just waiting to be discovered, the prospect of freedom and independence drives me into the grip of gold fever, a malady against which Boom himself has remained immune.

I can now understand the old Australian prospector who had fossicked for the better part of his life and had still found nothing much. In response to my question why he had, at his age, not given up when he had experienced so little success, he answered: ‘To tell all those who would boss me around to go to hell!’

Boom simply smiles; he knows and fears no master. And so, my fever also cools and in its place comes the old desire to wander into strange unexplored regions and experience adventures that test both courage and strength; to give in to that eternal primal curiosity about what might lie beyond the mountains. Nevertheless, the thought lingers in the back of my mind: ‘Just think what I could do with all that wealth!’

It was then that Boom, in his unassuming way, offered to take me into the Herzog Mountains for three months, to learn the trade of prospecting and panning for gold.

Salamaua in the 1930sThese three months would render me penniless but give me experiences that were worth ten times more than what it would cost. Three months of glimpsing the majesty of the untouched mountain world with its endless vistas and of listening to the sounds and the silence of the jungle. A magnificent landscape with a small white speck moving through it, where that speck is a human being with an internal emotional world of a similar scale.

New Guinea now holds me completely in its thrall. I have become obsessed with the idea of coming closer to the heart of this land, of penetrating into it and understanding it, no matter whether this would make me rich or send me home a pauper, or perhaps even destroy me.

But to turn this idea into reality I must first acquire the means to accomplish it. Fate is on my side. I am soon able to recruit twenty-five local workers and take up a contract offered by a gold company in Salamaua to build a road to transport goods through the swamps to a new airport, which is to become a link to the goldfields at Edie Creek.

Fever swamps – but what did it matter? Behind them on the slopes of the high mountains there are the forests, and the unknown. Many weeks of hard, unhealthy work go by. Then eight days ago, Soltwedel’s telegram reaches me, and I grasp his offer with both hands. Here at last is the opportunity to fulfil my dreams.

Biek, my boss-boy, is just coming along the veranda. ‘Master, sail he come now.’ He points out to sea where a small two-masted schooner can be seen entering the bay. It is the Namanula, and I walk over to the jetty to meet my new companions.

The first to approach me is my countryman, Soltwedel, a tall man dressed in khaki. He has a typically German face with a high forehead, brown eyes, and a strong straight nose. We greet each other cordially, for we had known each other in Rabaul. He introduces me to the geologist of our expedition, Mr Zakharov. A Russian by birth and extraction, Zakharov, with his thickset, sturdy figure, broad face, deep-set eyes, high cheekbones, and strong jawbone, is the epitome of the Slavic type. He shakes my hand firmly and, with his square forehead in broad furrows, says: ‘We are destined to share a great many experiences. I hope we will become good friends out there.’

‘I am sure we will,’ I reply with sincere conviction, returning his handshake. ‘Have you seen anything of New Guinea yet?’ I ask.

‘I only arrived from Australia a month ago, but Mr Soltwedel has told me a great deal about it on the trip over.’

‘That surprises me,’ I joke, ‘because, in spite of the twenty years he has spent here, I always have to squeeze him like a lemon to get him to talk about his experiences. People who have been in the bush for a while become taciturn.’

Soltwedel laughs and says: ‘Eating and drinking are sometimes more important than talking. Let’s go before hunger and thirst get the better of us.’ And he is right, because in this hot climate thirst always seems unquenchable.

Another episode of this story will be published in a future issue of PNG Kundu.

Editor’s Note:

This story, written in the 1920s, uses contemporary language. Some words, no longer acceptable, have been retained to maintain the authenticity of the author’s account.

About the Author, Ekke Beinssen

Peter Beinssen, a member of PNGAA and son of the author, provided us with a copy of Matapui for publication in PNG Kundu. It tells the story in some detail of an expedition that searched for gold in the area inland from Salamaua in 1929-1930. It describes the physical and mental challenges they faced and adds another perspective to the history of European involvement in Papua New Guinea.

Peter Beinssen, a member of PNGAA and son of the author, provided us with a copy of Matapui for publication in PNG Kundu. It tells the story in some detail of an expedition that searched for gold in the area inland from Salamaua in 1929-1930. It describes the physical and mental challenges they faced and adds another perspective to the history of European involvement in Papua New Guinea.

A later version of Matapui was published in Germany in 1933. However, this unpublished version is the earliest and most historically accurate. It was translated into English by the author’s daughter, Dr Silke Beinssen-Hesse.

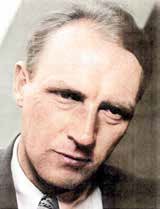

The author of Matapui, Ekkehard (Ekke) Beinssen, was born in Sydney in 1899. His father was a German wool broker who lived in Hunters Hill, Sydney at that time. Ekke began his education in Australia but when he was 11 his father decided to move the family to Germany so the children could learn the language and finish their schooling there. The family was in Germany when the First World War began. Born in Australia, the three children were Australian citizens under Australian law but in Germany they were German citizens. Thus, when Ekke turned 18 he was conscripted into the German Army (pictured right). He served on the Western Front where his unit opposed allied forces, including Australians, in the Battle of Passchendale. Ekke survived the war and in 1922 he completed a degree in macro-economics in Germany. In 1927 he returned to Australia and towards the end of that year he went to New Guinea where he had various jobs leading up to managing the expedition described in his book. At its conclusion he returned to Australia for life-saving surgery. In 1931 he returned to Germany. After Hitler came to power in January 1933 Ekke became involved with a movement that opposed the regime. Many members of the group were incarcerated by the Nazis, but thanks to his Australian nationality, Ekke was able to escape to America. His fiancée followed him, and they were married and lived in California for some time. In 1935 Ekke returned to Australia where he took over the management of his father’s wool business.

Like many other German families in Australia Ekke, his wife Irmhild and three children (Silke, Wally and Peter) were interned during World War II. Their fourth child, Konrad, was born during their internment. In September 1944, the family was released and moved to an orchard property near Orange in NSW. They remained there until the end of the war after which Ekke returned to the wool-broking business. Ekkehard Beinssen died in Sydney in 1980, and his daughter, Silke Beinssen-Hesse, has written a detailed, currently unpublished, biography of her father.

Like many other German families in Australia Ekke, his wife Irmhild and three children (Silke, Wally and Peter) were interned during World War II. Their fourth child, Konrad, was born during their internment. In September 1944, the family was released and moved to an orchard property near Orange in NSW. They remained there until the end of the war after which Ekke returned to the wool-broking business. Ekkehard Beinssen died in Sydney in 1980, and his daughter, Silke Beinssen-Hesse, has written a detailed, currently unpublished, biography of her father.

Editor’s Note:

We are indebted to Peter Beinssen and Silke Beinssen-Hesse for information about the life story of their father.

Part 2 can be found HERE