The Life of a Young Geologist in the 1960s – MALCOLM CASTLE

The mining industry was going through a boom cycle worldwide with companies like US-based Kennecott Corporation investing in exploration in Australia and New Guinea in a big way, and the idea of the adventure of a career in geology in New Guinea was fascinating to me—tramping about in strange jungles where normal men rarely ventured, tales of head hunters and cannibals behind every tree and reliving the lifestyle of the early explorers.

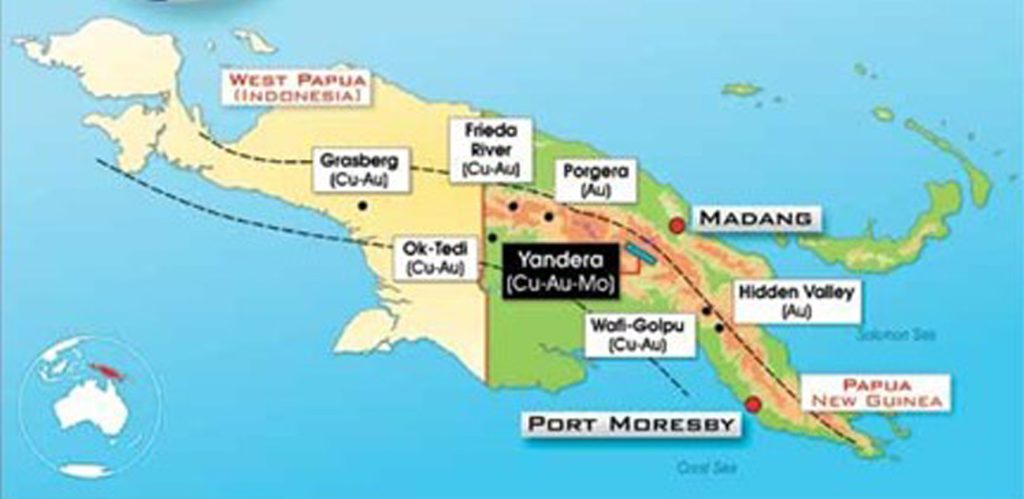

Exploration in Yandera

In the 1960s the focus was on the hard-rock potential at Porgera in the Western Highlands Province (after independence in 1975 now in Enga Province), 600 kilometres north-west of Port Moresby. With the help of the Administration, companies such as Bulolo Gold Dredging and later Mount Isa Mines (MIM) took an interest and began to drill test the Waruwari hardrock resources.

But in 1965 Kennecott began exploring the known copper mineralisation in the Yandera-Bundi area (examined and rejected by other geologists in July 1964), in Madang Province, before establishing an exploration centre—helipad, accommodation and geochemical laboratory—just outside Goroka in mid-1966. This was overseen by American Joe Swinderman.

The exploration work was commenced by Mark Foy based in Sydney, and I joined him in that halfway through 1966—also out of Sydney.

The work was centred on the Yandera porphyry copper project and lasted for a few years. The field trips to the area, where we lived in a bush camp for about six weeks, were followed by a couple of weeks back in Sydney to charge the batteries. The office was on site at the Yandera field camp.

The Goroka camp was set up after that when several other projects were being worked on. Geologists from Kennecott were exploring in the Mt Hagen area and the Star Mountains—

where Ok Tedi was discovered.

Getting to the Yandera camp was a bit of an ordeal! First leg was a plane ride from Sydney to Port Moresby by Lockheed Electra turboprop airliner (Qantas) and then making a connection, first to a local DC3 left over from the Second World War, and later to a Fokker Friendship aircraft for a flight across the Owen Stanley Ranges to Madang. That usually meant an overnight at a seaside hotel (not resort quality) and an early morning flight in a light aircraft, Cessna 206, to Bundi airstrip.

Bundi was a local administrative centre manned by a couple of patrol officers (kiaps). The kiap was district administrator, commissioned policeman, magistrate, gaoler. If he was in a remote area he may well also have

been engineer, surveyor, medical officer, dentist, lawyer, and agricultural adviser. The kiap system grew out of necessity and the demands made by poor communications in impossible country—the man on the spot had to have power to make the decision.

Just as important as the Patrol Post at Bundi for us was the Catholic Mission Station. They had a pretty laid-back attitude to life and focused mainly on educating the local children. Kids came from far and wide and were put up at the mission school. They were well fed and it was a good start to their lives. The Brothers were very hospitable and offered us a bed and meals before our trek further into the mountains.

Yandera was a good many hours walk from Bundi (depending on level of fitness). The tracks were well maintained so walking was easy enough. We had a string of porters to bring in our baggage and all the food and equipment required. Kennecott had built a small camp out of local timber and bamboo.

The Yandera Project area was the subject of intensive, drill-based exploration programs by several companies, including Kennecott Copper and BHP, during the late 1960s and 1970s.

The historic exploration work, which included 102 diamond drill holes totalling over 33,000 metres, culminated in the preparation of a mining study by BHP, identifying the Yandera system as containing one of the largest undeveloped porphyry copper systems (with ancillary molybdenum and gold) in the southwest Pacific.

Recognising that their field staff had little better than a rudimentary knowledge of the porphyry copper targets they were seeking, Kennecott arranged in early 1968 for five junior geologists—John Clema, John Eckersley, Doug Fishburn, Mark Foy and me, to attend a company-sponsored two-to three-month Porphyry Copper Workshop, which included visits to mines and prospects in the Southwest USA so as to familiarise participants with characteristics of the deposits.

Canadian geologist, Gerry Rayner, took charge of the Goroka operation in 1968. In May, geologists Doug Fishburn and John Felderhof, European field assistants, Tom Harvey and Chris Larkham, together with Papua New Guinea Nationals, Mangu, Peter and Fuse from Bundi, proceeded to Oksapmin, the nearest airstrip to the eastern boundary of Kennecott’s project area, to begin exploration of the section of the mainland spine westwards to the (then) West Irian border (the Star Mountains).

The initial assessment of the resources available at Yandera were not seen to be that attractive to a large American copper giant, and it was time to move on to more widespread exploration. Kennecott formed a Joint Venture with BHP to continue the work at Yandera. My assignments in New Guinea included work at the Owen Stanleys and throughout the Highlands.

From the mid-1960s to the early seventies, vast areas of Papua New Guinea were subjected to first pass prospecting for porphyry copper-style mineralisation. This work was carried out at a time of relatively low gold prices. Thus, the exploration programs gave little or no consideration to gold as a possible exploration target.

Living in Goroka

In 1968 Kennecott had increased its exploration

staff and moved some married couples to Goroka. We had a compound on the outskirts of town for the office work and with accommodation for single staff and people passing through. Joe Swinderman was the first regional manager and lived there with his wife, Florence. Bob Jones was later in charge of the operation, and he lived in a large house beside the Goroka Airstrip with his wife, Tina and three sons. There were two other couples living there with the company—it was a close-knit company ‘mafia’ that often develops in isolated postings.

During field trips and exploration jobs for a few weeks at a time in the jungle, my new wife, Sue, was left to amuse herself as best she could. Internet and

e

mail was a thing of the future and air letters written on very thin paper were the only means of communication. Phone calls were out of the question because of the exorbitant cost and availability of a connection.

It must have been fairly lonely, as she relates:

After we were married in September 1967, Malcolm and I lived in Goroka until 1970 in a flat above the IOOF Hall—a local drinking hole, which Malcolm felt obliged to check out from time to time. To get his attention to come home for dinner I used to bang on the floor with the broom handle, but it made little difference. For the first year there were some single staff in town, including John Clema from Malcolm’s first days with Kennecott.

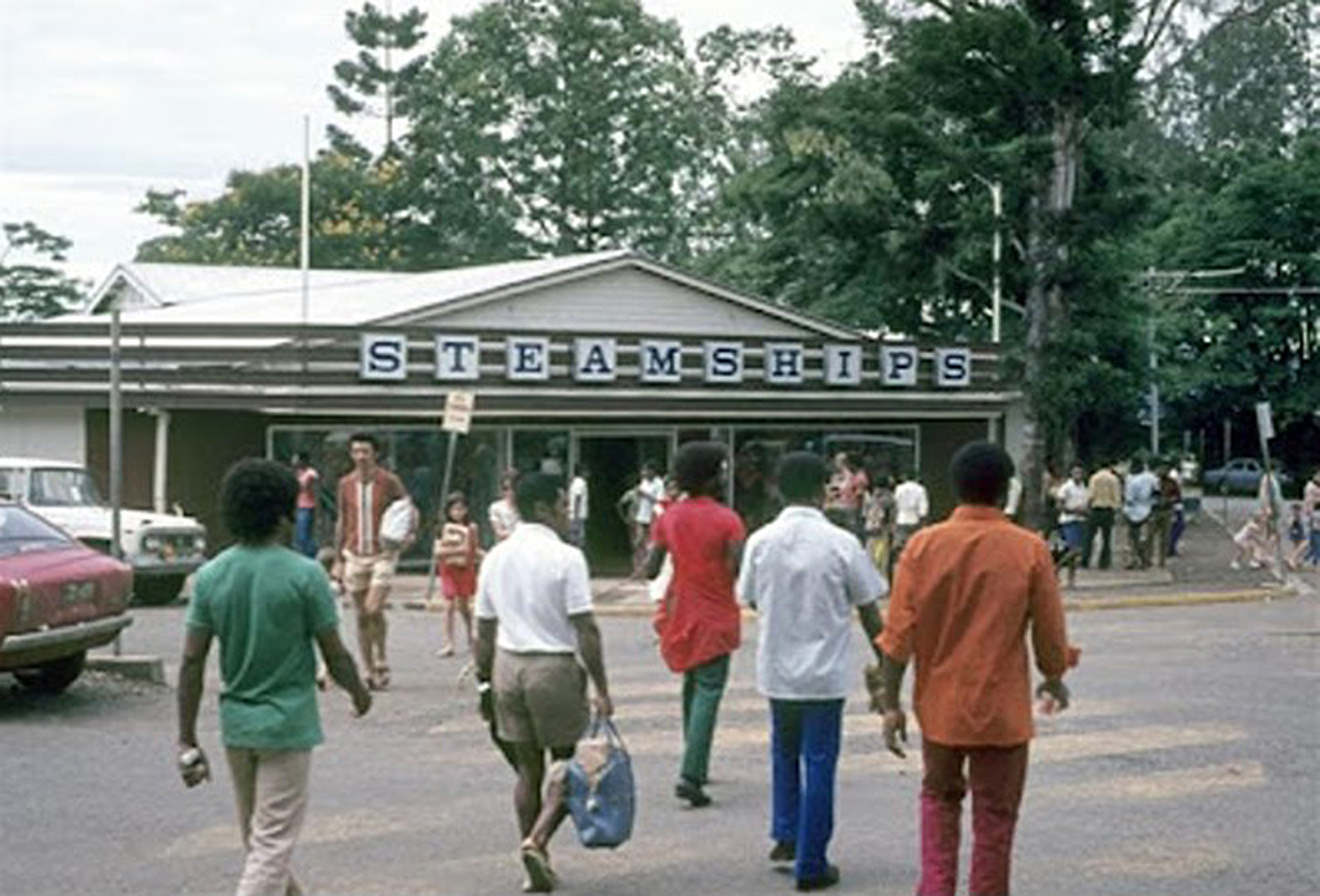

The highlight of my day during this period was a daily trip to the supermarket to buy some stuff. The maxim was never to buy too much so there was an excuse to go back the following day and buy something else. The attraction, of course, was to have a bit of human contact and a chat with the checkout lady.

I was happier with some female company and gave up ideas of ‘going home to Mum’. Instead, we decided to have a baby as there was no TV in Goroka and little else to do at night. I thought we were well prepared for the momentous event. Malcolm had bought a copy of Dr Spock’s famous book on raising children—so what could go wrong?

I was not convinced and went home to Mum for a bit of moral support. Our son was born at Auburn Hospital in March 1968 just a bit overdue. He was duly admired by all the family, being the first born of his generation.

Malcolm flew down for the event and spent some time getting used to being a proud father. He wasn’t there for the actual birth—this sort of thing wasn’t allowed in the 1960s. When he returned to the hospital, he brought a bunch of flowers. To save embarrassment he hid the flowers up the front of his jumper in the lift and hallway. He was oblivious to the sniggers of the various nurses he passed by—ever the romantic!

The Helicopter Crash at Ok Tedi, 1968

My main job was in the Eastern Highlands but on one occasion I went to Ok Tedi to fill in for a few weeks while one of the geologists went on a field break.

Weather at Ok Tedi was particularly treacherous with clouds rolling in on most afternoons and severe downdrafts developing. One afternoon in November 1968 the clouds came in early, and we had some people stuck on a helipad waiting to be picked up—they included Doug Fishburn and Robbie Robinson, the logistics chief for the project and several New Guinean field assistants.

Dave Binnie was a very experienced helicopter pilot with a lot of airtime in New Guinea and he probably had some misgivings about flying conditions. Nevertheless, we had people stuck in the bush who needed a cold beer at the end of a hard day.

At that time, we were using Bell 47 G3B1 helicopters made famous in the Vietnam War and the TV show MASH. They had served us well but were pushed to their limit in the Mt Fubilan area. Dave took off from the base camp at about 4 o’clock, before the clouds descended completely and with plenty of time for the pick-up. He landed on the creek-side pad and loaded his first two passengers, Doug and Robbie, and their gear. He was going to make a quick trip down to the base camp where I was waiting and go back for the rest of the crew.

As the helicopter lifted off from the pad it was hit by a strong downdraft and the pilot fought for control.

Unfortunately, the helicopter was underpowered in those conditions and the machine became unstable, rolled on its side and crashed into a small creek just beside the pad. It was only a fall of a few metres, and we believe the pilot sacrificed his own safety by rolling to the right so that his passengers might fare better.

Both the pilot and Robbie were killed on impact. Doug survived with a broken jaw. He crawled up to the pad and took shelter in a small bush lean-to.

The native field assistants, who were to be on the next helicopter load, stayed with Doug and sent one of their number down the hill by foot to the main camp where I was waiting for any news as the flight was some hours overdue.

A rescue party was organised to take whatever aid we could back to Doug while we waited for evacuation. The pilot had managed to send a mayday signal out on the radio as the helicopter plunged down. Other aircraft had picked this up and another helicopter was on the way.

Despite repeated and frantic efforts, radio communication was very poor in the area and I couldn’t transmit or receive from the base radio, and so it wasn’t possible to let my wife, Sue, know I was safe and well at Base Camp and trying all methods to get help and provide comfort for Doug. It was a sleepless night for all of us—as Sue relates:

The commercial radio stations had picked up on the mayday call and a short item was broadcast on the local radio saying that a helicopter had crashed in the Star Mountains, but it was not known if there were any survivors.

I was at home in our flat in Goroka listening to the radio when I heard this news item, and I was convinced it was the Kennecott helicopter. I knew Malcolm was working in that area and thought he might be on it! Others in the company also picked it up and quickly went round to our flat to be with me until the situation was known. This was a very gruelling experience and extremely upsetting.

I was five months pregnant with our first child and all the worst scenarios raced through my mind. What was I to do so far from home if Malcolm was injured or perhaps dead? I didn’t sleep a wink all night and it wasn’t until the following morning when the weather cleared, and the rescue helicopter arrived that the true picture was known. Malcolm was safe and Doug had survived with a broken jaw. The pilot and Robbie Robinson had been killed instantly in the crash.

This was a terrible blow as we had become close friends with Robbie. He had been with Kennecott since the beginning at Yandera and had been in New Guinea for many years. He was an open friendly man and loved to go off to Thailand or the Philippines for his holidays, and then recount lurid tales of his adventures. His passing left a big hole in our lives and was a serious blow to the company and his many friends.

The following morning the rescue helicopter arrived and airlifted Doug out, and he was flown to Port Moresby Hospital, where he spent a few weeks with his jaw wired up and a pair of wire cutters handy. He made a full recovery and returned to work with the Ok Tedi operation for some years.

Farewell to Papua New Guinea

After the helicopter crash Kennecott upgraded its safety regime and insisted on more powerful helicopters, and all passengers had to wear crash helmets. Doug returned to the project and drove it to a major development operation. Kennecott entered into a joint venture with BHP to develop the giant mine.

My period in New Guinea—peripheral to Ok Tedi and focused on Yandera and the Owen Stanleys— was among the most exciting and memorable of my career. Not many people get the opportunity to go to such remote places and meet people living in the stone age; to stumble across remnants of downed aircraft from the Second World War; to fly by helicopter into completely uncharted forests; to be involved in the discovery of one of the world’s greatest copper-gold mines; to survive a dose of malaria and to raise a young family. That is a fantastic experience!

Kennecott was a marvellous employer. I joined them in January 1966 straight from university and left four years later in 1970, to return to Sydney. As a geologist I had come of age. I was well trained by one of the best copper companies of the time and visited some of the most iconic copper deposits known in the USA at Bingham Canyon, Santa Rita, Morenci and the new Pacific Rim orebodies at Bougainville, Ok Tedi and Yandera.