Fireworks at Wau – Ross Lockyer

Jim Riley and I wandered about the New Guinea countryside and into the jungle at any opportunity, visiting villages, mission stations, gold sluicing operations, the old gold dredges and anything else that looked interesting. We would often drive up the

Bulolo Valley to Wau. It was only 30 kilometres, but it took us an hour to get there as the road was gravelled, pot-holed, windy, and narrow. The world-renowned Bernice P Bishop Natural History Museum headquartered in Honolulu, Hawaii, had a collection and research station based in Wau. Our mate, Ross Wylie, often accompanied us on these trips – before he was married that is.

The python at the Bishop Museum compound at Wau—(l-r) Peter Shanahan, Museum scientist, Ross Lockyer, Phil Colman, Ross Wylie, 1968

Jim, Ross, and I became mates with two of the resident scientists and we often threw a few cold SPs into the Land Rover and went up to spend a Sunday with them; Phil Colman and Peter Shanahan were both Aussies, and they were good blokes. Phil was a malacologist (snails and shells specialist) from Sydney and Peter was a small animal expert. They had a team of local New Guineans working for them on the collection side, and other scientists from Honolulu would visit on short-term projects. Their work was remarkably interesting, and Jim and I enjoyed catching up on their latest finds, observations and discoveries when we went up to Wau.

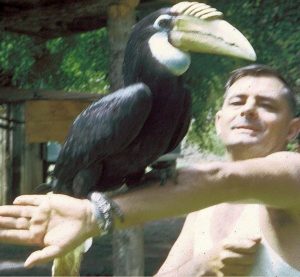

Phil and Peter had a collection of live animals and birds that they were studying. This changed or was added to on a regular basis. They had this huge pet python, which we used to carry about and wrap around ourselves. It was sixteen feet long, weighed 60 pounds, and was as thick as a man’s leg. They also had a pygmy possum, sugar gliders, a cuscus (which looks like a large golden possum), and a big Papuan hornbill known locally as a ‘woosh-woosh bird’ or kokomo. The woosh-woosh bird’s name denotes the sound made by its wings as it flies through the jungle among the treetops. The one at Phil and Peter’s house was a pet they had raised from a chick. It was about 130 centimetres long, with a 150-centimetre wingspan, and it had an enormous, hooked beak. It was the most comical looking bird I had ever seen.

We would often sit on the steps of the old house in the museum compound where they lived, drinking SP, and catching up on the local gossip. The kokomo would hear us from somewhere in the depths of the house and come hopping out in its most peculiar way, which was a bit like a wallaby leaping along. It would park itself on the top step and stare at us with one beady red eye and its head cocked to one side and wait. Peter usually had a big jar of ripe red coffee beans at hand, and he would throw one up to the bird, which would catch it neatly with the tip of its long beak, flick it back, and swallow it. Then we would start the count-down, and before we could count to a hundred—plop—the coffee bean, minus its outer red coating, would drop out of the bird’s rear-end onto the floor.

This trick would be repeated ad nauseam until either the bird got bored and hopped off somewhere else or we ran out of beer or coffee beans. This, of course, was all done in the cause of science. We concluded that the kokomo had a straight pipe with no baffles.

Wau was an interesting place. It had an airfield that was built on a hillside on a steep slope with a bend near the top. This was an important airfield during the Second World War, and there were many battles between the Japs and the Aussies trying to keep, or wrest, control of it. It was located roughly midway between Port Moresby on the south coast and Salamaua on the north coast, so it was a critical supply point for the defending troops. The old, corrugated iron shed on the western side of the airstrip was the original terminal building, and it was still full of bullet and shrapnel holes when I was there.

The surrounding area, particularly on the eastern side of the airstrip, was all scrub and low bush, and the Department of Forests decided, in its wisdom, to clear it and plant it with hoop pine. It consisted of a few hundred acres of rough land, and they brought up a gang of Chimbus from Bulolo to hand-cut the taller scrub and create a source of dry fuel to carry a fire through the entire area to prepare it for tree planting.

The day came when the cut scrub had dried sufficiently, and conditions were considered exactly right for a good burn-off. The Forestry guys positioned about fifty Chimbus around the perimeter of the cut area. At the signal, they struck their matches and lit their fires. The breeze was good and soon more than a hundred fires took hold then joined up. The burn started to move toward the centre. Then … bang, bang, BOOM! It sounded like a war had started up. There were bullets and shrapnel flying everywhere! The Chimbus and the Forestry guys hit the turf, trying to find something behind which to hide and dived for cover, but the battle just kept raging.

The Forestry Department had not done its homework—that area was vacant, scrub-covered, and with no native gardens for a good reason. The locals all knew that it was covered in abandoned ammunition when the war ended! Much of it had been buried under only a few centimetres of soil and some of it was practically on the surface, covered by years of scrub and weeds. A lot of it was scattered individual rounds, but there were also cases of cartridges, as well as hand grenades, a few anti-aircraft shells and various other explosives. The fire was out of control by this time and there were more explosions and metal and lead flying everywhere each time the fire front found more ammo.

The terrified Chimbus crawled away on their bellies into the surrounding jungle, and it was days before some of them were found and taken back to their compound at Bulolo. It was two days before many of the residents of Wau and the villages located near the airstrip ventured back to their homes. Miraculously, no one was killed, although bullets and shrapnel were found buried in walls around Wau for quite a while.

Editor’s Note: The preceding yarn is a chapter abstracted from the author’s book, Cannibals, Crocodiles and Cassowaries – A New Zealand Forest Ranger in the Jungles of Papua New Guinea.

The book is about his years as a forester in pre-independence PNG (1967–73). Website: rosslockyer.co.nz