Crossing the Saruwageds, Easter 1976 Part 1: IAN HOWIE-WILLIS

I left Papua New Guinea (PNG) in August 1973 after three years at Brandi High School near Wewak, and then almost six years at the University of Technology (Unitech) in Lae.

Following some time in England, I moved to Canberra in early 1975 to undertake a PhD degree in PNG History at the Australian National University (ANU). I went back to PNG for a fortnight for the Independence Celebrations in September 1975.

In February 1976 I returned to PNG for seven months’ archival research and interviews at the University of Papua New Guinea in Port Moresby and at Unitech. This was because my PhD topic was a history of the planning, development and politics of the PNG university system.

During those months, I lived through, and survived, the most exciting and most hazardous of my many adventures in PNG. This one happened during Easter 1976 while I was living back on the Unitech campus.

My next-door neighbour and bushwalking companion, Hector Clark, invited me to join him and two of his campus colleagues on a crossing of the Saruwaged Range. I accepted enthusiastically. Crossing the range had been an ambition of mine ever since I had moved to Lae in early 1968. Although I had taken part in various expeditions into the Saruwageds, I had never walked from one side to the other.

Our companions on this trip would be Robin King, a lecturer in Electrical Engineering and Matthew (Matt) Linton, who taught Mathematics. I knew neither Robin nor Matt, but we soon chummed up and enjoyed each other’s company.

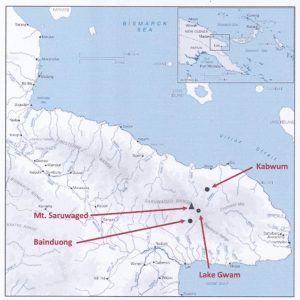

The plan for the trip was to fly by light plane from Lae to Bainduong, a village with an airstrip high on the southern or Lae side of the range. We would then engage village people there and in other villages along the way to help carry our backpacks up the steep tracks through the rainforest to the edge of the alpine grassland at about the 10,000-foot level (3048 m). We would camp there the first night then clamber up to the broad plateau forming the top of the ridgeline. If we had enough time and energy, we would climb Mount Saruwaged then cross the plateau and follow the trail down the northern side of the range. After that, we would pass through various villages on the northern side, making our way to the airstrip at Kabwum, a large village which was the headquarters of one of the Morobe Province’s administrative sub-districts.

The expedition went according to plan during the first day and a half. We arrived at Bainduong aboard the plane Hector had chartered. We had no difficulty recruiting carriers to help us carry our gear to the next villages, which might have been Tukwambet, Awen and Kisituen, then up the increasingly precipitous and indistinct paths through the rainforest to the open grassland. After paying off our carriers, we pitched our tents then spent a reasonably comfortable night in a sheltered clearing.

The next morning, we trekked up through the tussocky grass. By early afternoon the clouds began rolling up from below but when we were high enough, we caught a glimpse of Lae and the Markham mouth and of the coast down to Salamaua and beyond. The view was magnificent. The Huon Gulf coast lay before us as if on a huge map. Higher again, we could see to the north-east. In the distance on the far side of Vitiaz Strait was the south coast of New Britain stretching away to the horizon.

But then, as Scots might say, the excursion began to gang agley.

As more and more dense banks of cloud enveloped us, visibility was reduced to a few metres. We could not see any of the peaks or pinnacles to take compass bearings; and the faint track soon vanished amid the thick grass.

The Huon Peninsula showing the Saruwaged Range, Mount Saruwaged, Lake Gwam, Bainduong and Kabwum in relation to Lae

By the time we were antap tru (at the very top), on the broad generally level plateau of the ridgetop, we were uncertain where we were on our map. We were trudging across tundra, a soggy, dismal grey-brown wasteland of bog moss interspersed with stretches of flat lichen-carpeted stone littered with frost-exfoliated rock shards. On either side were numerous ponds of shallow water, several about 50 metres and more across.

We had little idea where we really were. Our map, not very detailed but the best then available, was little help. It neither showed the contours at that height nor displayed the features of the landscape we were crossing. We were, we reluctantly conceded, lost! We wandered back and forth for an hour or so, trying to find a track and peering through the mist to try to locate features from which we might take bearings.

My guess, after consulting more recent maps and Google Maps satellite images, is that we were somewhere between Mount Saruwaged to the west and Lake Gwam to the east. They are only three kilometres apart, so if that was where we were, they were nearby.

At 4,121 m (13,520 feet), Mount Saruwaged is the highest point along the range. It is a rocky conical pinnacle that rises above the main ridge line. Lake Gwam is a tarn of glacial origin. In a hollow fed by numerous small streams, it is roughly stadium-shaped (i.e. rectangular with rounded corners), but with several bays and promontories along the sides. It is about 630 metres long and 455 metres wide and lies at 3517 m (11,539 feet) above sea level.

Both the mountain and the lake must be among the most inaccessible places in all PNG. Few people ever go there. Those who do are generally from the highest villages below the plateau. They go there seasonally during the drier (‘less wet’) months, roughly May to September, to hunt the wallabies inhabiting the alpine grasslands. Some villagers maintain bush-material huts there for these excursions.

All routes across the Saruwageds are difficult, dangerous and demanding. The perils include precipitous slopes, landslides, steep, slippery, narrow tracks, slimy logs bridging rushing torrents, paths that peter out, the dense, tangled rainforests, few campsites or shelters and the exposure and bleakness of the swampy ground along the broad ridgelines. Severe weather conditions are the norm. Dense fogs reduce visibility to several metres as the clouds roll up from the valleys below each afternoon. The almost daily, hours-long deluges of rain drench the mountains. Fierce winds sweep across the exposed plateau above the treeline; while periodic frost, and gale-driven hail, sleet and occasionally snow are additional hazards for travellers in the high Saruwageds.

One couple who braved the Saruwageds about 23 years ago were the geologists Wibjörn Karlen (1937–2021) of the University of Stockholm and Michael L. Prentice from the University of Indiana. They were there to examine the lake. Amazingly, after setting up camp there, they built a raft so they could take core samples from the lake floor. A safe bet would be that that was the first time the lake had ever been sailed on! Equally surprising is that now a bamboo helipad is laid out beside the lake. This is for the helicopters bringing in engineers to service a nearby telecommunications relay station.

And as if that is not enough, a Melbourne adventure tour company now offers an eight-day expedition from Port Moresby to Mount Saruwaged for €2915 (Aus$4894). On the first day out from Port Moresby the tour party reaches Kiroro village, the highest in the Kwama River headwaters on the north side of the range, where the company maintains a guest house. Day 2 involves an ascent to a place called Mono further up the range in the forest at the 2450-metre (8039-foot) level. From Mono on Day 3, the party climbs to ‘Grassland Camp’, a campsite above the treeline at the 3680-m (12,074 feet) level. Day 4 sees them arrive at the next camp, near Lake Gwam. On Day 5 they trek across the tundra to their base camp at the 3940-m (12,927 feet) level on the south-eastern flank of Mount Saruwaged. From the base camp, over the next two days, they climb the mountain and several other nearby 4000 metre pinnacles. Day 8 they are helicoptered to Lae for their flight back to Moresby. For an extra $750 the company provides a local carrier, hiring whom it recommends strongly.

The Melbourne company’s clients obviously see much if their trip runs according to schedule. We, however, saw neither the mountain nor the lake as we wended our uncertain way across the plateau. That does not mean they were not nearby, just that the all-enveloping fog was so dense we could not see them. That makes me wonder what contingency plans the company might have for parties that become fog bound.

Part two can be found HERE.