A Manitoba Family in Gili Gili: 1925–29 KATHERINE PETTIPAS—PART 3

From 1925 to 1929, William McGregor, a Canadian farmer/rancher worked on the Gili Gili Plantation in the Milne Bay District as the Head Stockman for Lever Brothers. Accompanying him on this venture were his wife, Kate, and their teenaged daughter, Rubina. While Kate used photography and correspondence to document her experiences, Rubina acquired indigenous artefacts and natural history specimens. Part 3 of their story describes highlights from the artefact collection.

My interview in 1984 with Rubina (Ruby) Miles of Brandon, Manitoba, was one of the highlights of my curatorship at the Manitoba Museum. Ruby (1909–2003) was born in Maple Creek, Saskatchewan to Kate (née Rowe) and William Thom McGregor. A farming family, the McGregors immigrated to Australia in 1921 where Ruby completed her high school education in Sydney. In 1925, the family moved to the Gili Gili plantation.

A forthcoming and gentle woman, Ruby fondly reminisced about her time as a teenager at Gili Gili and enjoyed sharing her experiences with me. Despite having to save her father from an attacker as well as witnessing an instance of domestic violence, Ruby was surprisingly non-judgmental of the Papuans. In fact, she insisted that she viewed Papuans as ‘just another type of people who lived differently from her’. Somewhat of an armchair anthropologist in her

later years, Ruby was an observant student of cultural practices and was able to discuss the subject matter of her mother’s photographs in some detail. For example, she described the specific types of clothing that were assigned to various workers and was able to attribute hairstyles to particular villages.

While at Gili Gili, Ruby remained close to her family unit and lacked white peers of her age. She loved her pets, exploring her environs, experimenting with growing plants, and horseback riding. However, life at Gili Gili was hardly a carefree or idyllic tropical experience for the teenager who was required to assist her father with caring for the stock, even helping with the laborious task of cattle dipping. Likely as a result of her involvement with tending to the herds, Ruby did develop a friendship with ‘Teddy’, her father’s Papuan hired hand, whose main job was the care of new calves. On one occasion, Teddy gifted Ruby a pig and in return, she left him a writing desk when the family returned to Canada.

Local conditions and lack of transportation restricted the family’s movements. According to Ruby, white personnel were discouraged from wandering off the plantation compound for fear that their lives would be endangered. However, there were short trips to a few friends in the immediate area and likely to Samarai. On one occasion, Ruby had a tour of a rubber plantation facility.

Ruby attended several local ceremonial events with her parents. She fondly recalled spending many evenings sitting on the verandah with her mother listening to the singing and drumming emanating from the villages located around the edges of the plantation. The night sky would be lit up from all of the burning camp fires. On at least on one occasion, she witnessed a ceremony to honour a deceased man’s remains. Her recounting of the event prompted Ruby to contrast Western and Papuan attitudes related to death and dying, Papuans being more accepting of death as a part of living.

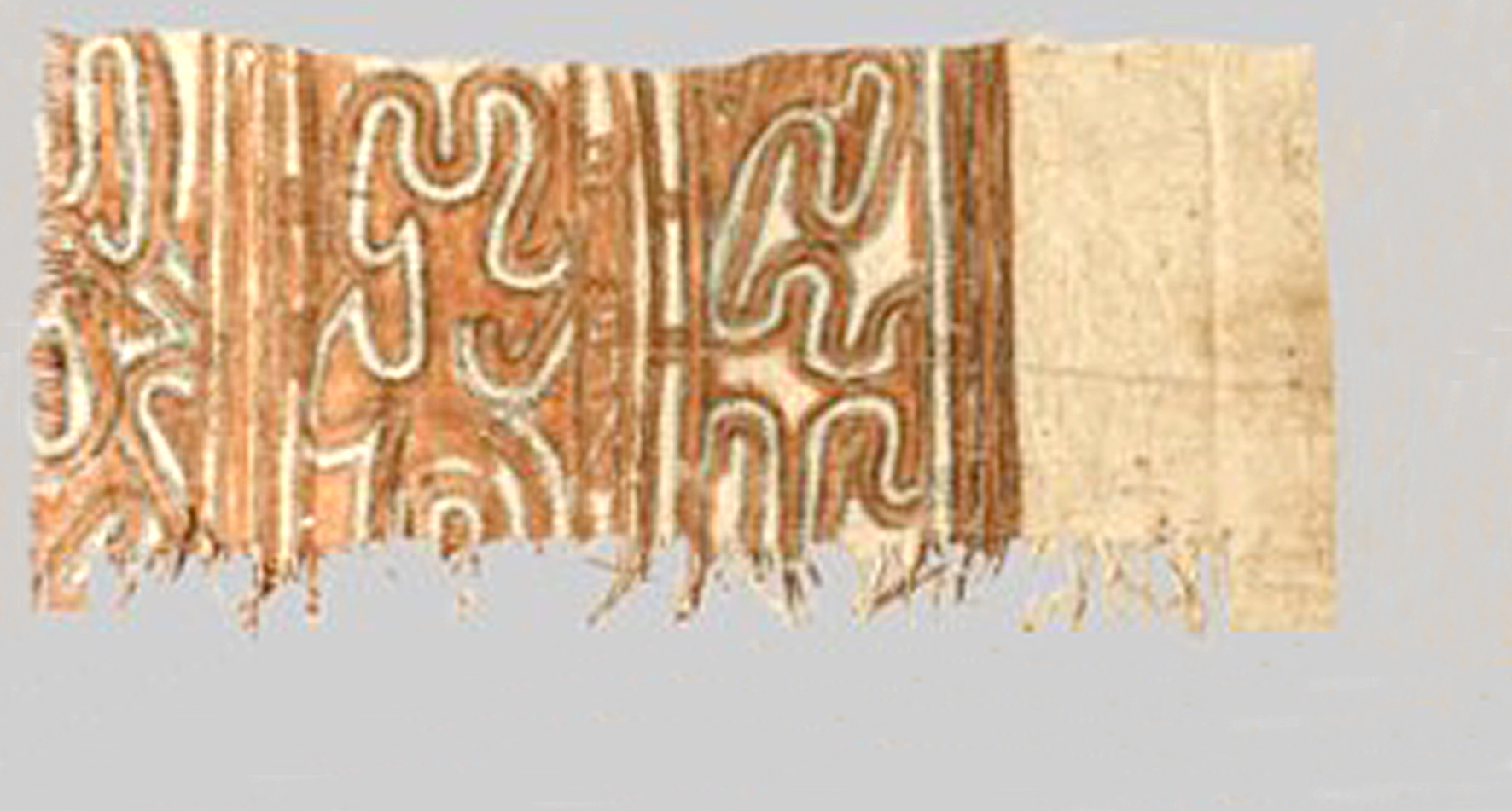

Keenly interested in the local culture, the teenager traded sticks of tobacco for a number of small portable objects from labourers and their family members. Some 60 artefacts and natural history specimens, including butterflies, were transported back to Canada in 1929. The largest items were examples of indigenous clothing.

In addition to three pieces of bark cloth, there are four women’s plant-dyed fibre skirts. One of these skirts was presented to Ruby’s mother as a Christmas gift by local women. This gesture may have been an indigenous example of reciprocal exchange given that Kate did sew clothing for the children and some of the women. Fondly known as the little ‘white woman’, Ruby herself was gifted a traditional outfit including Birds of Paradise headdresses.

In addition to the skirts, Ruby donated a number of other indigenous personal items to the Manitoba Museum including two fly whisks made from cassowary feathers fastened to a wooden shaft; two fishbone sewing needles; wooden and bamboo hair combs; plaited plant fibre arm bands; fibre belts, shell armlets, and two decorative nose bones.

Ruby also collected four wooden dishes, three fibre baskets, a woven fibre band used to carry large baskets and three wooden napkin rings. A decorated wooden mortar was used for processing areca (betel) nuts. Five wooden lime sticks and three gourd lime pots are associated with the consumption of areca nuts.

Ruby’s acquisition of two shell armlets is particular noteworthy since further research has revealed that these objects are similar to those, or may have, in fact, been traded through the Kula ritual exchange system. Known as mwali, these polished conus shell armlets are very similar to those collected by anthropologist Dr. Bronislaw Malinowski in the early 20th C. They are one of two main types of objects (the other being red shell neckpieces) involved in the Kula Ring or ritual exchange system. This ceremonial exchange tradition is well-documented and is linked to personal prestige and status. Item H4-0-312a likely had beads and other objects strung through the holes with a plant fibre twine. For a comparable reference see Plate XVI in Malinowski’s publication titled Argonauts of the Western Pacific, London: George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1922.

A decorated hour-glass-shaped kundu featuring a lizard skin head was also donated, but the circumstances of acquisition were not recorded. The letters ‘ABUAI’ have been painted onto one side of the drum. This lettering likely indicates the surname of the maker. Three wooden napkin rings and a small carved wooden seated figure are inlaid with limestone chalk. Acquired as Indigenous-produced art objects, further research indicates that the figurines are near-identical to traditional protective figures that were produced in the Massim area.

Ruby wearing gifts of a fibre skirt and Birds of Paradise feathers, she also wears woven fibre and shell armlets from her collection, EP 1289, MM

The few natural history specimens that were donated to the Manitoba Museum include a cassowary egg, a Bird of Paradise skin, a tanned spotted cuscus skin, a python skin and the scutes from a Hawksbill sea turtle. Ruby collected hundreds of specimens of butterflies while she lived at Gili Gili and a few were on display in frames in her Brandon home.

Ruby’s collection is a modest one when compared to the thousands of artefacts that were amassed by the various colonial agencies of the day and transported back to Western nations. In my opinion, as with children’s art, artefacts that were collected by youth – in this case, an expatriate teenager, are not generally represented in museums or art galleries. For this reason, Ruby’s collection of personal mementos from her time at Gili Gili offer an interesting dimension to the McGregor Family story and museum collections.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Manitoba Museum staff who provided photographs for these articles and to Christy Henry, University Archivist, SJ McKee Archives, Brandon University for forwarding me copies of photographs and correspondence from the Rubina Miles Fonds. A note of appreciation is also owing to the hard-working staff associated with the publication of PNG Kundu. Thank you for allowing me to share the Miles story with your readership.