My Expatriate Life – Part 1

This is the first part of Diane Bayne’s account of her life as an expatriate. It covers her time in Port Moresby and Lae.

When visiting Bangkok, I’ve wondered what it would be like to live there. The sensations of colour, smell, movement and noise are so overpowering, as is the humidity and heat. It’s contrasted by the gentle politeness of the quietly spoken Thai people. I’m sure expatriate living in Bangkok would be unique to Bangkok but, as is the way with expatriate living, it would mean adjusting, learning, accepting and rethinking attitudes as well as lifestyle.

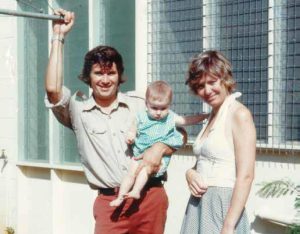

My first expatriate experience was in 1974 in Papua New Guinea. In those days the Department of Education, in South Australia, ruled that if you were a married woman and six months pregnant, you had to resign. At that time my income abruptly stopped. For my husband, a pilot, full time flying jobs were limited in Australia but positions were available in Papua New Guinea. We had struggled along and now had a baby. That was it. There was a job on offer so off we went without a second thought.

I wasn’t prepared. I’d never been out of South Australia apart from Melbourne and I’d never experienced the tropics. I remember stepping off the aeroplane into what felt like a furnace. I’d never felt that drenching humidity before. But my husband was there to meet me and it was so good to see him. He’d been in Port Moresby for a month ahead of me, training on the aeroplane and learning about the job. He was thrilled to be fully employed and flying in an interesting country like Papua New Guinea. As we drove through the streets of Port Moresby, I saw crowds of Papua New Guineans walking by the side of the road, women with belongings piled on their heads and/or babies on their backs and the men with lesser loads. I was shocked at what I saw as poverty and particularly shocked at seeing so many spitting blood from their mouths! But no, this was ‘betel nut’ I was told. Chewed with lime, it gave a heightened, slightly altered state of mind and when they spat it out it was bright red.

We eventually arrived at the company accommodation. It was an upstairs, very Spartan three bedroomed apartment with louvered windows, overlooking other buildings and lush, green vegetation which was a real contrast to dry Adelaide. There were brilliant huge flowers I’d never seen before. There was no air conditioning but there were fans whirring around on the ceilings, giving relief to the humid air. My eight-month-old daughter was hot and red faced even though I’d taken off most of her clothing and given her water. I’ll never forget those first few hours after my arrival.

After a few days my daughter and I started to adapt to this new climate. It was a strange experience seeing the Papua New Guinean people speaking differently and walking in crowds everywhere. But it was lonely. I missed my extended family, my friends, my lifestyle and the familiarity of home. My husband was away nearly every day flying aeroplanes. I knew no one. I couldn’t drive. I had to wait for my husband to come home if I needed to get to the supermarket. There was security wire over the windows. I looked after my baby girl who seemed fine but I was not prepared for this culture shock. Slowly I got to know people, other wives living nearby, how to get to the shops and how to do things in this strange tropical country.

I look back and see it was quite daunting for me although I remember feeling an acceptance and excitement about my new situation too. I was a naïve country girl although I’d lived in the city. No one in my family had ever been overseas. In fact, in those days most people didn’t travel much. Wealthy people took overseas holidays and students went on working holidays to the UK and maybe Europe but I hadn’t actually known of anyone who had left Australia to live in a different country. So, this experience for me, in the early seventies, was initially like being foisted onto a different planet. It opened up a new world which also helped me understand my husband and his family. He was born in Malaysia. His Scottish parents had lived there most of their lives where his father had been a rubber planter. Eric and his sisters were sent ‘home’ to Britain to boarding school before coming to Australia. He had a very different upbringing compared to mine. Expatriate living had been a foreign concept to me but through living it, I was now starting to develop an understanding. I decided I liked the tropics. There was an extraordinarily intense beauty about it and I felt healthy and alive. But then, after barely settling in to Port Moresby, we moved to Lae in the Morobe Province.

In Lae we lived in a small compound flat, next door to a supermarket and a cinema. Next to our front door was a beautifully sweet-smelling frangipani tree with a shiny green tree frog sitting in it. There were lots of people around the streets constantly knocking on our door looking for work. We were told to keep everything locked and safety chained. There were other young pilots, all single, living in our compound and they would gravitate to each other’s flats, talk flying and party. It was pretty noisy. Our neighbour regularly woke us up with Bob Marley’s ‘No Woman No Cry’ at full volume (I hear that song now and it’s so poignant; I’m right back there). They’d often come to our flat for a beer and talk flying with Eric. They all had one thing in common; an absolute obsession with flying aeroplanes. It was here that I was initiated into the social life of an aviation wife in PNG. To pilots there was no other topic of conversation. It was all about aeroplanes, more aeroplanes, airstrips, weather, flying stories, flying ‘hours’ and the ever present ‘seniority list’. Wives and girlfriends listened and some of the stories were interesting but after an hour or so at any one time, it could become boring. We turned to each other. We were mostly Australian, one who was English and there was a South African family with two children, one about our daughter’s age. We all came from different places and we were all young, in our twenties, drawn together through our pilot partners. Our stories and backgrounds were all different and diverse. My world was opening up.

With Eric away a lot, he decided to electrify the windows with a power supply equal to a cattle fence for added security, something that would be highly illegal in Australia. We would turn on the electrified windows and doors most of the time and we often heard screaming and shouting as someone got ‘zapped’ trying to break in, usually late at night. One day I put some tomatoes on the louvered windows in the kitchen to ripen. I retrieved them a couple of days later, forgetting that I’d turned on the electricity. I got ‘zapped’ but I remembered after that!

I enjoyed Lae. It wasn’t quite as big as Port Moresby but it was greener and everywhere the growth was quite dense and lush. Banana palms seemed to grow freely. The road to the Lae airport, in those days was adjacent to the town and it was an avenue of massive flame trees. They were spectacular. I saw some huge spiders sometimes but the biggest problem was mosquitos and I put a mosquito net around my daughter’s bed. I played tennis and bought a sewing machine. Eventually I succumbed and employed a “house girl”. Other women and wives convinced me saying, “You should,” and “It will free you up”. It felt odd at first. No one had ever done my housework for me. My house girl came every day, washed floors and dishes, dusted, washed and ironed. Her three young children played in the garden. One, a baby, slept naked in a ‘billum’, a woven bag, hung up in a tree. She’d go out every now and then, hose him down for coolness and cleanliness and breast feed. Then she’d come in, clean my baby’s bath, wash and sterilise the baby bottles and wash my nappies. We only communicated via my limited Pidgin English and I would sometimes catch her looking at me. Maybe she was confused with my white women’s complex ways of baby care, compared to her simple, common-sense approach. It’s things like this that are important. Makes you think and reflect about your own accepted values and ways of doing things. That’s part of the reason why expatriate life is a worthwhile experience.

Diane Bayne

Part two can be found HERE