Matapui

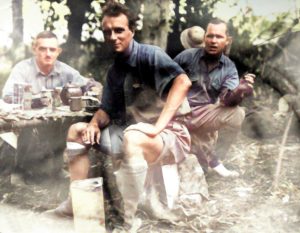

EKKE BEINSSEN

Part Two

The previous edition of PNG Kundu published Part 1 of Matapui, an account written by Ekke Beinssen about a 1929 exploratory expedition that sought to find the source of the alluvial gold being sluiced out of the newly discovered goldfields of the Bulolo River and Edie Creek. In this second part, Beinssen describes the departure of the expedition from the picturesque Buang village of Mapos, perched on the steep hillsides above the Snake River in the Morobe District south of Lae.

Our departure from Mapos takes on the appearance of a triumphal procession. Even before sunrise, the mission square is crowded, and by seven I have distributed the loads to our twenty-five boys and the sixty hired porters and paid them. It is the custom to pay for carrier services in advance and there is almost no known case where the porter has not delivered his load to the agreed destination. There may have been occasions when a sack of rice was nibbled if the porter’s hunger became too great. That should not happen to us this time because we have bought a mountain of garden produce and have distributed it to the porters. Each man must carry five days’ worth of sweet potatoes on top of his load. Our provisions have been calculated sparingly because we are hoping to buy more produce on the way.

Zakharov’s haversack and camera are given to Naie with strict instructions for him to remain close by. It contains the most essential scientific instruments required by our geologist to understand the geological characteristics of the areas we traverse. And if you observed Zakharov as he walks, you would be convinced that nothing could escape his sharp, deep-set eyes, be it a major formation, some layering of rock, or simply a small stone. He reads the landscape in terms of millions of years and tells the story of the living earth as if he had witnessed its evolution. But it is not just the past that he reads like a horoscope. He can spend whole nights talking about weathering, oxidation, displacement, and eruptions of subterranean volcanos; and he sees future changes in the landscape that further millions of years will create.

Soltwedel, in comparison, does not have Zakharov’s scientific training to read the terrain geologically but, since the discovery of the goldfields here, he has acquired a great deal of practical experience. Whenever Zakharov comments that there might be something of interest here or something there,

Soltwedel contemplates the practicalities. Would mining be economically viable, suitable for machines and sluice boxes? For an individual or a company? Could one build an airfield nearby? How long would the preliminary work take, and how much labour and how much capital would be needed? Soltwedel always has his mind on what resources can be utilised, and if Zakharov gets carried away by something that is geologically interesting but of no economic significance, then it is Soltwedel who will redirect his attention to the practicalities of the real world.

Whilst I am fascinated by the approaches of both these men, it is the interaction of nature and man that is of greatest interest to me. Consequently, we three complement each other very well, and it is no surprise that now, as we leave Mapos, my dog, Lump, and I are the first to set out while my two comrades follow. My gaze is directed into the distance, but Zakharov’s eyes will scan the ground and take note of whatever is in close proximity.

The track leads from the airy heights of Mapos down to the Snake River. In the language of the natives, it has the beautiful name Sagae, with a slight emphasis on the ‘ae’. Sagae means fairy tale or legend in Mapos. Not far from here, there is the Gangwae, meaning song, which runs into the Sagae. Thus, from this point on, the river could well be called the ‘The River of Sung Legends’.

From a rocky prominence which, had it been situated on the Rhine River, would certainly have provided a good site for the castle of a robber baron, I can see our expedition moving down the mountainside. There are almost a thousand people – men, women, children, and infants – like a black snake against the light green of the slopes.

Our boys, who will now be gone for some time, walk freely. Brother, sister, mum, dad, or friend are carrying their loads. They are decorated with flowers and feathers tucked behind their ears, into their hair, or under their arm and knee bands. They are brightly painted with white and coloured lime; all are wearing their best lava-lavas and strutting along like roosters. Boisterous yelling, calling, and singing accompanying the procession, and the village pigs dive off into the bushes in fear.

We descend to the Sagae River where it is fiendishly hot compared to the cool of Mapos – the difference in altitude is 500 metres. Most plunge into the water to cool off. Only our porters stand stiffly on the riverbank, reluctant to spoil their body decorations. Just as hot as when they arrived, they continue along the narrow track by the river, while behind them the farewelling party, like an army of freshly bathed mice.

It is virtually impossible to describe the magnificence of the track we now follow. To our left are the mighty grass-covered mountains, rounded and sparsely vegetated with oaks from the tertiary period. To our right, gigantic grassy walls rise almost vertically, their marble foundations awaken the sculptor within. One can imagine the outlines of grotesque heads and figures. Every now and again these walls are sliced by waterfalls that murmur new stories from other regions into ‘The River of Sung Legends’. The river winds its way through the gorges of the mountain range, cascading white within the deep green of the reeds on its banks. It will flow for weeks, months, and years until it eventually pours the entire wealth of its treasure of legends into the ocean – the ultimate destination of all rivers.

It is three o’clock and ahead of us black rain clouds move across the sky. To the right, halfway up the slope, there are several natural caves that should offer good shelter for our porters and their loads. I therefore decide to call a halt. It will probably take some time before the stragglers catch up.

Our small three-man tent is pitched on the grassy cover of a small hill. It has a slanting roof and is open on three sides. Freshly cut grass, kunai as the natives call it, serves as bedding. Night falls, the rain passes, and above us there is now a cloudless, pitch-black, starry sky. All around us there are a hundred small fires where our porters are camped with their friends and relatives. A large group has gathered at one place, and they are singing the same melodies that we heard in Mapos.

A few young, high-spirited lads have climbed the hill opposite our camp and set fire to the kunai grass. Soon the entire slope is alight. The background is now glowing red, and the fiery tongues that leap into the night sky are bright yellow. It is not dangerous as the river lies between the fire and our camp.

From our beds in the tent, we can make out three figures silhouetted against the fiery background. They are standing on a little rise and singing with high shrill falsetto voices. I am reminded of the mullahs in Persia and Arabia when they call the faithful to prayer from mosque towers. Like them, our singers incline their heads and cup their hands over their ears. All others are now silent and listening.

Throughout the night the drums continue to accompany the singing with their threatening, evocative monotone. The burning mountain, the murmuring of the river, the monotonous melancholy song, the rhythm of the kundu drums, and the black, naked figures squatting around their campfires or walking noiselessly through the night, all merge to create an unforgettable dream which has magically become reality.

The three of us sit in silence on our beds of grass. The atmosphere is too powerful and too moving to allow for conversation. But behind each of our separate silences there are probably much the same thoughts: Who are we three men in the middle of this foreign world? Three men from different continents who now find themselves dependent upon each other in this wild land. Three white men amongst dark exotic people! If only it were possible to untangle the threads of fate. Why us three? Why here?

The fires have now burnt down, the singing has ebbed, and the cloudless, pitch-black, starry sky stretches above us. Only the kundus beat on until dawn, like the beat of excited hearts.

Part Three will be published in a subsequent edition of PNG Kundu. It will describe the frantic attempt to get the critically ill geologist Zakharov to hospital. The full story of this expedition can be accessed via the PNGAA website. The descendants of Ekke Beinssen welcome any comments from readers: beinssen@gmail.com