Outside—The life of CTJ “Bill” Adamson: Michael Bird

Charles Thomas Johnston (“Bill”) Adamson was born on 17 January 1901 between the proclamation of Australian Federation on 1 January and the first Federal election in March. Bill’s father was Charles Adamson, an Australian surgeon living in England and his mother was Margaret Johnson, a descendent of Sir John Murray, a member of the Challenger oceanographic expedition of 1872. Bill was the elder brother of William and “Bun” Adamson. Despite an excellent public school education at Sherborne School in Dorset, he turned away from family privilege upon graduation. After learning the wool trade at Bradford Technical College, he emigrated to Australia in 1923 to work with a shearing team, spending the next few years doing the rounds of the sheds in Queensland. After a period cutting cane in north Queensland he left for Papua to try his luck on the goldfields in 1926.

In Papua he prospected with variable success for the next decade, often the only European, many days from assistance in precipitous terrain. He came to know the Kunimaipa and Tinai Valleys, the Lakekamu goldfields and the Goilala like the back of his hand. Near Mondo on the Auga River he wrote of his prospecting:

Worked like a bastard all day and got a good bit of dirt through….Great prospects where Roy (Morris) was but I suppose it will be the usual thing… Wonderful weather and no rain all day. Feeling pretty tired and sore tonight but a man can work OK in this climate.

As the depression took hold he augmented his prospecting income by growing coconuts and then running mule transport. He provided transport first for the Archbold expedition to the summit of Mt Albert Edward in 1933 and then for the redoubtable woman entomologist Evelyn Cheeseman in 1934. Of “Miss Cheese”, as he called her, he quickly came to the opinion:

Miss Cheesman made a good trip of it… a good walker and is a game lady. Had a very interesting talk to her in the evening.

In 1935 Bill joined the Papuan Government service as one of Sir Hubert Murray’s “Outside Men” and achieved a measure of fame for his part in the epic eight month—and completely bloodless—Bamu-Purari Patrol into the Southern Highlands. This was the longest exploration in Papuan history and the first where an accurate map could be produced by virtue of the party being able to determine both latitude and longitude using radio time signals. At the end of this patrol he commented:

I can’t say I feel too cheerful as it means the end of the freedom of the bush and the return to being a junior patrol officer again…a lamp arrived and it is a godsend after a month in the dark….So ends our period of privation on Xmas day!

After leave in the UK, he returned to government service and helped Ivan Champion open the Lake Kutubu Patrol Post: Bill’s “haven of tranquility” in the Southern Highlands. Here he spent spent two continuous years patrolling into the Southern Highlands, involved in the business of “first contact” on a daily basis.

At the beginning of WWII, Bill joined the Australian Navy and served first on mine-sweepers in the English channel and Western Approaches (“The North Atlantic nearly killed me spiritually with its everlasting fogs, gales and cold…’ “then the flower class corvette HMS Aster and then in command a converted Norwegian whaler, the Silhouette, in the Indian Ocean. After Japan entered the war in 1942, Bill slowly made his way from Alexandria in Egypt, via Australia, to Papua where he served first as beachmaster at Oro Bay and later in command of the survey ship HMAS Stella assisting the Allied offensive in New Guinea. In the final year of the war he assumed command of the HMAS Taipan, one of the “cloak and dagger” snake-boats of the Services Reconnaissance Department training out of Freemantle. Of his largely Malay crew drawn from the pearling fleet of Broome he later wrote:

I liked them very much. They were always spotless and better turned out than the white crew we carried to work the guns. They were also better seamen.

After demobilization he returned to Papua in the Government service but found the post-war bureaucracy too hard to bear, leaving after less than a year to become the owner of the Ou Ou Creek plantation near Kairuku, close to his prospecting base was of the early 1930s. After almost two decades at Ou Ou Creek, in the midst of a deteriorating personal and political situation, he made the decision to “turn down the page”,’ moving to Cooktown in 1964. The estate of one of his cousins provided enough money to buy some land and build a house he named “Kemenagie” after the local name of a prominent peak near Lake Kutubu (the sign still hangs on the house to this day). He started recording the weather for the Bureau of Meteorology and in the dry season would take a run up Cape York in his land cruiser, making astrofixes of every campsite at night. He wrote to Syd Smith:

I lead a very controlled life—the same thing at the same time every day—and the days pass very quickly. I have no one to argue with except the dog, since the poor old cat passed away last year at the age of 18.

His health began to fail and in 1978, shortly after he married Patricia Hanush, he shot himself. He left a son, Charles, born of his relationship with Aiva Aua of Oroi village way back in 1933. He also left a surprisingly large circle of relatives for one who vowed never to continue the Adamson line. He is buried in the cemetery at Cooktown.

Bill was well educated and imbued with the “stiff upper lip” values of the British Empire at the turn of the last century. He believed in judging a person by their actions rather than their words. He was a big man who valued sporting prowess, physical fitness and the capacity for hard work. When prospecting and patrolling in the Papuan bush, he carried a load along with his carriers and suffered incredible privations as a matter of course. He was awkward in company but greatly respected by his peers. He played the mandolin and practiced yoga on his verandah at Ou Ou Creek Plantation after the war.

Although he partly subscribed to the prevailing notion of innate European superiority over the “natives” he lived for months at a time with no European companions and established a deep rapport with indigenous labourers in his employ. Bill was the second best of the pre-war “Outside Men” of the Murray administration of Papua, after Ivan Champion. He did not kill anyone “Outside”, although he did try, saying in his diary after an “affray” in the Mubi Valley in 1939:

I meant at the time to kill the bloke who rushed up to the crest but later on Atkinson found that the wind gauge of the rifle I used was out by 1°. This probably saved the man from an early death and myself from a magisterial enquiry.

Bill Adamson lives on in the diaries he wrote: almost a million words. These provide an exceptional window into experiences and attitudes shared by many Australian men of the Federation generation, which continue to shape contemporary Australian attitudes: drought, depression, itinerant jobs, the lure of gold and exploration, privation, war, relationships, mateship, reverence of Anzac Day and a cold beer.

Bill was an astute observer at many scales, from observations of his fellows and circumstances on a daily basis, to opinions of world affairs. He commented on events from the declaration of WWII:

Germany has invaded Poland and war looks to be a certainty….I think we are for it this time… Apparently British ships are being torpedoed all over the place and I hope we have not been caught napping again

to the sacking of Whitlam (writing to Syd Smith):

the roof certainly fell in on Whitlam … I was so staggered I thought a rum and milk was called for. As the full implications emerged I had another and so on until Dr Pat and old Wakefield arrived to find me in a glow, so to speak … seems that Australia is not yet ready for Socialism. The local commos were staggered and one actually burst into tears at the pub. The hippy bludgers seem to be aware that all may not be as smooth as it has been for them…

In many ways Bill Adamson has sunk into history with barely a ripple, yet a fish Haephaestis Adamsonii, Adamson’s Grunter), a bird (Coracina caeruleogrisea adamsonii, the Stout-Billed Cuckoo-Shrike) and a grass (Admis grass, local name for molasses grass in the Auga valley) bear his name. For those who remember him, his name resonates as one of the greats of Papuan exploration between the wars.

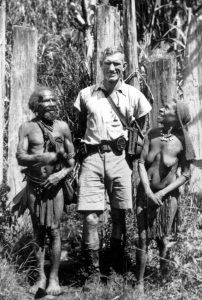

Bill Adamson patrolling in the Augu Valley, ex Lake Kutubu Police Camp circa 1938