The Road to Officialdom – Hell and Back THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY CITIZENSHIP DEBATE

By Patricia Chow

This article is a very brief overview of how Australian citizenship came about in our PNGCCAA community. There are some people who may still have memories of these times, and one rainy day should jot down their thoughts to fill in the gaps in the records.

As always, when we delve into our own history and personal stories, sometimes it makes for difficult reading, however, the community knowledge is important so that someone, perhaps your future great-grandchild, will appreciate how we came to be here.

The elders of our community have passed on some understanding of how their parents or grandparents, who were skilled tradesmen and workers, and their wives and perhaps a youngster or two, came from China to work and settle in a Pacific island country now known as Papua New Guinea. This process of migration of a particular group from one region of the world to another is not that unusual, and there are many examples to be found in Australia, like the post-WWI migration of southern Italians to Leichhardt, Sydney, or of a few German village families to South Australia.

From childhood days, it was always taken for granted by the writer that our Australian citizenship had something to do with being born in pre-independence Papua New Guinea when New Guinea was a mandated territory of Australia and thus it was somehow an ‘automatic’ right. (A half- baked notion that was! Patricia says).

Troy Lee’s citizenship case (Minister for Home Affairs v Lee [2021] citation FCAFC 89), which was told in Kundu News, Issue 80 Spring 2021, has highlighted the fact that, typically for new migrants, citizenship begins with naturalisation—the process whereby one becomes ‘a full member of the Australian community’.

In the words of the late James H Woo OBE, ‘It took us a long time to be given the privilege of Australian citizenship and we prize it highly’ (Cahill, p.254). Cahill’s account of the citizenship issue in this book is recommended reading for those interested in gaining a fuller understanding of the historical background of a complex issue. In other words, for those of us with parents and grandparents who settled in or were born in the former Territory of Papua and New Guinea, Australian citizenship was not ‘automatic’, nor was it granted without much debate at all levels of the Administration.

Colonial Times

Papua, the southern part of pre-Independence PNG, in 1888 became a protectorate under British control but, by 1906, it was handed over to Australia to be administered as an external territory. New Guinea on the other hand, was the northern part of pre-Independence PNG, with a different civil administration to that of Papua, as before World War I New Guinea was a Protectorate of Imperial Germany. Indeed, the writer remembers when her grandfather, Gabriel SY Chow, had said without any rancour, that in his youth, he used to doff his hat to the Germans of that time and had learnt a smattering of the German language.

At the end of WWI, the German administration of New Guinea was handed over to the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) in September 1914, and this period of military administration ended when the League of Nations conferred the mandate of administering New Guinea to Australia on 17th December 1920 (p.86, Cahill). The New Guinea Act 1920 came into force on 9 May 1921, which was the beginning of the civil administration of New Guinea.

At the end of World War II, the territory of New Guinea became a United Nations trusteeship. Unsurprisingly, after the turmoil of two World Wars, ‘the legal position of Chinese in New Guinea after 1945 was thoroughly confused. They were denied Australian citizenship, the British citizenship status of those born in Hong Kong or Singapore was ignored by the Australian government, their movement between New Guinea centres was controlled, and they were banned from entering Papua’ (Cahill, p.205). The New Guinea Annual Report 1947/1948 recorded the number of Chinese residents at 1,769 men, women and children; however, that number had varied greatly depending on who was in charge at the time.

Many would remember that the two territories were jointly administered and known as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. TPNG was what this writer used to write as the destination of letters sent home to Rabaul, written from the Randwick home of grandparents during the early 1970s. TPNG existed until midnight of 15 September 1975 and the next day was Independence Day for the new nation of Papua New Guinea.

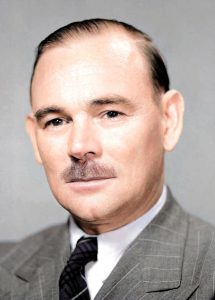

The Minister for Territories

In early 1951, the Prime Minister of the time, Robert Menzies, appointed Paul Meernaa Hasluck as Minister of Territories, which included responsibility for the Northern Territory, Nauru, Norfolk Island, Cocos and Christmas Island, and Papua and New Guinea.

He was an outsider in regards to the then Territory of Papua and New Guinea as he said that initially he knew nothing of the place. The appointment however proved to be fortuitous, especially for the Indigenous people of PNG. With Hasluck’s prior experience representing Australia at various United Nations commissions, he brought a fresh perspective to the local administration and in his own recollection, the ‘stuffily rank-conscious’ community (Hasluck, p.13). He carried out his duties there for the next thirteen years with a firm conviction in the UN mandate to facilitate the political development of the country as well as addressing the social and fiscal issues arising with development. His tenure as the minister was not going to be smooth sailing.

From the outset, he observed that there was an atmosphere of racial segregation and he sought to improve matters by proceeding to ‘remove any discriminatory treatment of the Chinese and mixed-race people [and] to break down the social barriers between them and the Europeans’ [p.32]. He estimated that there were about 2,000 of Chinese origin, 11,000 Europeans and about 1,300 of ‘mixed race of various origins’.

Hasluck wrote that:

As for the Chinese, I saw at once that the only way open was to give them full Australian citizenship, with the right of permanent residence in Australia … these ideas were quite contrary to the prevailing opinion in the Territory and in Australia at that time [p.31].

Despite his personal conviction, the question of citizenship was to remain unsettled for another six years, as there were strong opposing views.

Australian Protected Person (APP) Status

In June 1950, the New Guinea Chinese Union – executive members included Gabriel Achun, Thomas Mow and Wong Shoon, had already presented a petition to the UN Visiting Mission to the Territory detailing their grievances and aspirations; nearly a year later, they also met with the new minister, Hasluck.

The lack of domestic political support for the granting of citizenship more broadly to the Chinese in New Guinea was somewhat addressed by new legislation (October 1951) under the then Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 – 1950 that introduced a class of persons, who were:

… born in New Guinea whether before or after the making of the regulation, who are not British subjects, are expressed to be within the class of ‘Australian Protected Persons’ [Cahill, p.246].

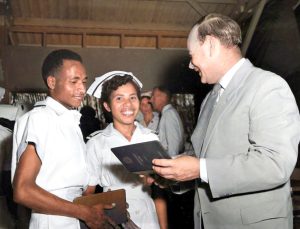

Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, handing certificates to graduate nurses at the NSW University of Technology, Wollongong division (later the University of Wollongong). Source: University of Wollongong Archives

For the APP, this meant that they could travel under the auspices and protection of the Australian Government, however, it did not extend to including full citizenship rights to permanent residency.

Eddy Yun, now aged 84, recollected that he travelled as an Australian Protected Person when he first arrived in Australia, aged 16 or 17. Eddy makes a great story of how puzzled the immigration official was on inspecting his official papers that day so long ago, however, its validity was finally accepted and Eddy was ushered onwards for his high school studies at Bowral’s Chevalier College.

The discussions about citizenship for New Guinea Chinese took place during the sunset of the colonial period when what is generally known as the ‘White Australia Policy’ was in force. There were, however, a number of voices speaking out against the prevailing atmosphere of exclusivity.

One of these was Father James Dwyer MSC, who supported the Rabaul Chinese and made representations to the TPNG Legislative Council, which established in 1951 that the Chinese and those of mixed descent be granted Australian citizenship (Cahill, p.252). It is also noted there that Fr Dwyer might have also had his heart set on getting a new Rabaul church built with a more settled congregation. (Cheek of the suggestion! Patricia).

Taking a Seat at the Table

Finally in August 1956, with gathering support of the citizenship issue, Minister Hasluck made the recommendation to Cabinet for the granting of citizenship to Chinese and other ‘Asiatics’. On 16 June 1957, The South Pacific Post reported that Minister Hasluck, had announced:

The Government has decided to give to those Asian residents who were born in the Territory, and to those who were not born there but were living there not under any immigration restriction, the opportunity to become Australian citizens by naturalisation [Cahill, p.254].

Prior to this momentous decision, Minister Hasluck wrote that there was what he modestly called a subsidiary incident – a visit by Prime Minister Menzies and Dame Pattie Menzies to Rabaul, when they were officially welcomed:

… by the Chinese community in their own hall. In courtesy and social grace this function far outshone any other … and moreover at that time the Chinese hall, built by themselves, was the most pleasantly modern building in the town.

To his delight, the Prime Minister was greeted by ‘a succession of … well-mannered young Chinese men’ (Hasluck, p.333) who turned out to be Wesley College Melbourne Old Boys, as was Menzies himself. (The gathering of well turned-out ladies pictured in ‘Old Rabaul’, Kundu News, Issue 75, now looks to have been the Ladies’ function in honour of Dame Pattie).

In those times, one could imagine that the acquiring of citizenship meant that one now had a legitimate and equal voice, and that one could have a future without the anxieties of deportation to China—the far away land of the ancestors—or uncertain prospects in a future independent PNG.

The idea of the permanent residency on mainland Australia, however, was probably not uppermost in mind, as the small Chinese communities dotted around the New Guinea Islands were thriving and participating in many aspects of the good life and the good people of the tropics.

References:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-16/timeline-of-papua-new-guinea-road-to-independence/6748374

Peter Cahill, Needed-But Not Wanted: Chinese in Rabaul 1884–1960, Copyright Publishing, Bris., 2012.

Paul Hasluck, A Time for Building, Australian Administration in Papua and New Guinea 1951-1963, Melbourne University Press, Vic. 1976.

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hasluck-sir-paul-meernaa-18555

Thank you to Denis Chow & Davina Chan for supplying additional resources.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published as Part 3 in the Kundu News, Issue 82 (continued from Issue 80), per kind approval of Patricia Chow, Kundu News Editor, for the Papua New Guinea Chinese Catholic Association of Australia.