Panguna Mine—A House with a View

Simon Pentanu

PANGUNA on Bougainville Island has many stories to tell. There is a helluva lot to see—enough beauty and destruction to boggle the mind whenever you visit up here.

Once upon a time, this was a place barely known outside the local area, thriving on its own, peopled with scattered villages and hamlets in the green alpine, unscathed mountains along the island’s Crown Prince Range. All travel to and from the coast was on foot. I spent time in Panguna in pre-mining days during construction of the mine, and also during the early years of mining on university vacation employment, working. I still travel up there to show friends what’s left of one of the biggest open-cut mines in the world, and share some of Panguna’s history before the mine started.

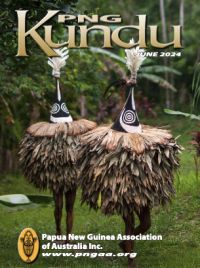

My daughter took the photo (above) when our family travelled to Panguna with our grandchildren and their friends, while on an end-of-year school vacation from Port Moresby. The photo focusses on a young man reminiscing in an open haus win offering a clear view of his immediate surroundings. When I saw the photo I wondered what he was thinking as he gazed across the desolate and denuded landscape that is his Panguna today. Maybe he was thinking about what the future holds for him. Like all active youngsters, he walks around the perimeter of the old minesite. Perhaps he wonders whether the mine will ever be resurrected in his lifetime.

This was once a forested valley, the rich hunting grounds of his ancestors. But he is from the generations who were born post-conflict, well after the mine was closed. Perhaps he is too young to fathom what went on here on such a massive scale, and why it all stopped; maybe he is asking himself why it all stopped when he sees alluvial miners are now scurrying around all day long, trying to extract gold, using manual methods, and in conditions bordering on slave and child labour. Some children who are caught up in alluvial mining may never see the inside of a classroom. Others may pay their way through some of or all their education.

Many of this young man’s generation have missed out on the stories and tales shared by family gathered around the fireplace, about how their great uncles kept the clans over the hill at bay from encroaching on their land. Our young man in the photo probably cannot imagine the enormity of the BCL mining operation and why his uncles could not keep the company out of his ancestral lands (as they did with other clans), before the company came and exfoliated their forest trees and denuded the landscape to dig up Panguna. He will not be able to remember how his ancestral village and other villages were relocated, dislocated, and displaced.

On bus rides to Arawa, the youngster might notice other villages on the hills nearby that are thriving, where people are still interdependent, cultivating their land, and taking what is on offer from their forest. This is not his experience. He can only imagine how his village might have once been like this.

The damage to the land and the river systems – right down to the deltas on the coast and into the sea, caused by alluvial mining in Panguna and elsewhere—is perpetuated by the lifting of the moratorium on mining activities. It is causing, debatably, worse environmental damage than mining by BCL at Panguna. The downstream lower tailings areas continue to bear the brunt of the effluent and sedimentation, but the worst culprit is mercury. Yes, solid liquid mercury.

Since Panguna closed, the prevalent use of mercury has left a terrible long-term toxic legacy, as alluvial miners use it indiscriminately, dumping it on land, and into creeks and river systems. We may deny, dispute, or ignore this, but we all do so to our detriment. We will reap a bitter harvest of lung, liver, and kidney damage, not to mention fish kills, and other environmental harm, if we do not accept our collective responsibility and take firm action locally and through legislation.

The following words are attributed to the late Mr Francis Ona, who is often quoted and touted as Panguna’s and Bougainville’s environmental warrior: ‘The duty of man is to protect his land.’ Ona is probably turning in his grave when he sees what is going on at Panguna, especially when it comes to the destructive methods being employed in alluvial mining, particularly with the use and abuse of mercury. The contamination and pollution of river systems and creeks that find their way to the seas surrounding Bougainville Island stands to be the biggest disaster. The people and the Island will suffer in the long-term if nothing is done now.

This is one of many stories about Panguna. It may sound gory, but sadly it is a true story. And as stories go, if we miss the lessons of the tale, the repercussions and consequences can be disastrous. Bougainville and its future generation will pay for our apathy and ignorance.

The words of Francis Ona would ring even more true if he were here today and rephrased what he said to: the duty of every Bougainvillean today is to protect their land from themselves.

Editor’s Note: This article was written especially for PNG Kundu by the Hon. Simon Pentanu MHR, Speaker, Bougainville House of Representatives, and the photograph on the previous page is courtesy of Laurelle Pentanu, 2023.