Crossing the Saruwageds, Easter 1976 Part Two

Ian Howie-Willis

Part One of this three-part series described how the author and his three Papua New Guinea University of Technology (Unitech) companions lost their way in dense fog while crossing the broad plateau forming the main ridge of the Saruwaged Range north of Lae. This instalment describes their difficulties in descending from the plateau to the villages on the northern side of the range.

Guided by Matthew (Matt) Linton, the mathematician and best map-reader, who was good at mentally calculating distances, heights and angles, we decided to follow a northerly compass bearing across the tundra antap tru (i.e. on top of the Saruwaged Plateau). By about 4 pm we reached the escarpment on the northern edge of the plateau.

Matt pointed down the steep slope below us: ‘We must follow that ridge,’ he announced, ‘because it will lead us down to the nearest villages.’ We trekked down for maybe 15 minutes until the slope had narrowed to a ridge spine that dropped away in front of us for what seemed like hundreds of metres. Matt declared that that was the ridge we must descend.

Robin King, Hector Clark and I looked aghast at each other: ‘Going down there would be suicidal!’ we protested. The three of us said we would be better off clambering back up to the plateau to see if we could find another way out. But Matt was insistent: ‘I’ll go first,’ he assured us, ‘follow me and I’ll show you we can do it!’ We replied that we would not follow until he had reached somewhere safe and could clearly see the way forward.

Matt set off cautiously, step by step. He had only descended about five metres when his feet slithered from beneath him. He began sliding down the slope and out of view on his backside. He desperately grasped at the tussock grass to halt his descent and prevent himself from hurtling into space. Fortunately, Matt got a firm grip on a small shrub without uprooting it. He lay there shocked, grasping his shrub for a minute or two, then turned himself over. Slowly, ever so carefully, he climbed back to where we were standing, horrified at what we had just witnessed. We were only about 20 metres above him but he took 20 minutes to reach us.

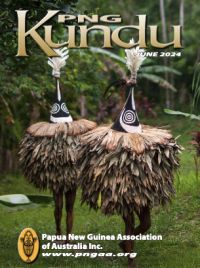

The camp in a sheltered hollow on the lee side of the northern escarpment of the Saruwaged Range. Matt Linton (left) and Robin King are perhaps wondering whether the tent that Hector Clark has just erected is weather-proof (Source: Hector Clark)

Matt then sat there exhausted for about 15 minutes as he regained his composure. He knew he had had a close call, that he had escaped death by a whisker. We three others refrained from saying so, but we all realised that if the four of us had ventured down Matt’s ridge the risk of someone dropping to his death would have multiplied by a factor of four.

When Matt was ready, we wearily plodded back uphill to the plateau. That took us half an hour. On the way sleet was swirling around us. By the time we reached the top we knew that night would soon be falling, so we began looking round for somewhere to pitch the tents. We soon found a sheltered hollow on the lee side of the escarpment. It offered protection from the prevailing northerly winds. That was where we camped.

What followed was the most miserable night of my entire life. I was grimy, wet, cold and depressed, uncertain what the morrow might hold. My chief worry was that we might not find a way down from the bleak, inhospitable plateau. We could die of exposure there; we could fall down some precipice; and we might run out of food. The others, I guess, were thinking much the same.

Heavy rain fell during the night. I was sharing Hector’s two-man tent, which lacked a built-in waterproof floor, and which in any case he had not erected to be completely weatherproof. During the night we discovered a rivulet trickling through the tent. Despite our groundsheets, the bottom ends of our sleeping bags were saturated. After that, we sat as far away from the steady streamlet as we could, the dry portions of our sleeping bags wrapped round us like shawls. We dozed fitfully in that position for the rest of the night.

(Left–right) Robin King, Matthew Linton (front), Ian Willis and Hector Clark at their campsite, looking worried after not finding a track down from the northern escarpment of the Saruwaged plateau (Source: Hector Clark)

By first light, about 6 am, I was up, dressed and clambering from the tent to ‘answer a call of nature’. I walked about 20 paces, looked around to see if this was far enough from the tents, when, lo and behold, to my great surprise there at my very feet was a path. To my right it plainly led down from the escarpment; to my left it ran past our campsite and back across the plateau.

‘Hey, cobbers, come and have a Captain Cook at what I’ve just found!’ I yelled. (I enjoyed using such archaic Australianisms because my three companions were genteel Englishmen.) The others stumbled from their tents and joined me. In amazement and relief, they gazed to the right and the left. No doubt about it: we were on a path! If we followed it, we would surely find the north-side villages Matt had been promising us before his near miss the previous afternoon.

Breakfast that morning was a more cheerful meal than yesterday evening’s gloomy and frugal repast. We speculated on where we might end up that night, but because we did not know where we were, we could not really tell. We were packed up and following our path by seven o’clock. The further we went, the easier the track was to follow. It zigzagged sharply down a knife-edge ridge with steep slopes on either side, but there was little chance of losing it. If we had stumbled off the path, however, we would have fallen hundreds of metres.

Eventually, the steep descent put pressure on our knees. We rested every hour or so, sitting on the track, relieving our sore knees, thus avoiding wobbling when we began walking again. Soaking in the sunshine was a welcome change from slogging through yesterday’s heavy fog, sleet and rain. By about mid-afternoon our track took us down from the grassland and through the rainforest. The further it went the less precipitous it became. We realised we were coming into village territory when we could see secondary growth off to the right below us. That meant old and disused gardens, and so a village must be somewhere up ahead.

At about 5 pm the track broadened as it reached a riverbank, where it swung left and skirted the shallow but turbulent river. By this stage, we had been following our path for 10 hours. After another half hour, we saw a welcome sight as we rounded a bend. About 50 metres ahead of us was a lapun (elderly chap). All he was wearing was the traditional mal, a short tapa cloth apron held in place at the front by a G-string. ‘Apinun, yangpela!’ (Good afternoon, young man), I called out. He shrieked in fear, spun around, and tore off down the track. He was soon lost to sight in the gathering dusk. As night fell, we continued along the path, confident that we must be approaching a village.

Within another half hour we could see flickering lights ahead. It was a party of village men holding aloft bomboms (palm branch flares). They were coming to investigate what had frightened the lapun. He had bolted back into the village screaming that four masalai (evil spirits) were chasing him. When they realised that we, harmless if dishevelled, white blokes were the masalai, we all enjoyed the joke.

The welcoming party then escorted us to the village, which was another 15 minutes away, up a steep ridge. Once we got there, they showed us to the Haus Kiap, and invited us to make ourselves comfortable. A couple of them lit a fire for us and said they would be back soon with boiling water for cups of tea and a bowl of freshly cooked kaukau (sweet potato). Meanwhile, we unrolled our sleeping bags so they might dry out, then lay back enjoying the feeling of relief after having reached safety at last.

Part One can be found HERE.

Part Three can be found HERE