WHEN HOME WAS A TRIP THROUGH HELL By Robert Coleman

Part 1 of 2 in Una Voce June 2014

Here is the story of one man’s war. It is a microcosm of the overall conflagration, the story of a small party of stragglers’ epic escape from the Japanese on New Britain…a story rich in drama, courage, endurance and an indomitable will to survive.

I n the long, lonely hours of the night, the memories still come flooding back over Bill Neave. They have been little dimmed by the passage of 35 years. They are still raw and painful; they still bring tears. There are still ghosts that haunt his sleep and make him reach for the sedatives prescribed by the Repat Doctor.

n the long, lonely hours of the night, the memories still come flooding back over Bill Neave. They have been little dimmed by the passage of 35 years. They are still raw and painful; they still bring tears. There are still ghosts that haunt his sleep and make him reach for the sedatives prescribed by the Repat Doctor.

There are still times when he sees himself again as a bearded skeleton of a man, clad in rags and racked with malaria, dysentery and plugging on through the eternal twilight of the dense, hostile jungle . . . starving . . . and kept alive, he swears, by prayer.

‘Anybody who doesn’t believe in prayer, he says today, ‘well, fair dinkum. I reckon he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ Bill Neave is a survivor of Lark Force, the 1400 strong garrison at Rabaul, New Britain, which was overrun by vastly superior Japanese forces on January 23, 1942, after saturation bombing. Only 400 or so eventually found their way back to Australia. The remainder perished – most of them in the sinking of the prisoner-of-war ship Montevideo Maru, off Luzon, in the South China Sea on July 1, 1942.

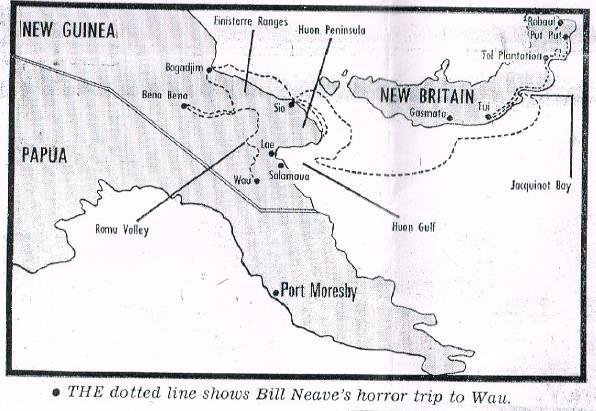

For 183 days after the capture of Rabaul, Neave and a handful of other Diggers slogged hundreds of miles through the almost impenetrable jungles and mountains, gorges and rivers of New Britain and New Guinea, living on what they could scrounge from the natives and constantly hiding from the Japanese.

They drifted hundreds of miles on mountainous seas in a rickety, over-crowded little boat to reach New Guinea with half a gallon of petrol left – only to find the Japanese had got there first. At one stage, Neave was given up for dead. His 5 foot 4 inch [1.62m] frame had wasted to 51/2 stone [35kgs] – half his normal weight.

On July 25 he reached Wau and was airlifted to Port Moresby. But the war was not over for Bill Neave. In its closing stages, he was back in the thick of the fighting with the Sixth Division at Wewak – and was with Pte Ted Kenna when he won the VC.

In April 1940 Bill Neave and a couple of mates, George Coates and Lance Howlett, enlisted in the AIF. They became members of the 2/22nd Battalion, the main unit of Lark Force. The garrison at Rabaul was a link in the slender chain of forward observation posts which Australia strung across its northern frontiers. It comprised the 2/22nd Battalion, some artillery and other attached troops. Neave arrived there on ANZAC Day 1941 – nine months before the invasion.

The garrison fought valiantly but was hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. It had been subjected to heavy bombing for some days and the coastal guns had been knocked out. Surrender soon became inevitable, Neave’s company had been pushed back into a gully. The company commander told his men he would surrender with them because if they had an officer with them, they were more likely to be treated properly as prisoners of war.

But, he said, if any wished to try to escape, they had a chance of being picked up on the south coast of the island if they could cross the Baining Mountains. He said any who wished to try to escape had his orders to do so and would not be treated as deserters.

Bill Neave takes up the story: ‘We were warned by the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit (ANGAU) chaps that it was impossible to cross the mountains. We had no food, no ammunition or medical supplies.

‘Most of the men surrendered. They looked at it in this light: if they surrendered their next-of-kin would at least know where they were.

‘I thought I would take the risk and try to get back if I could. I wanted to get back. I’ll tell you what: I was scared. Anybody who says he was not scared is not telling the truth. I was one of a party of six who left from that particular point. We picked up a couple of others in the jungle later.’

(More than 800 of Lark Force’s 1400, which included six nurses, were taken prisoner. The remainder, mostly in small parties, tried to find some means of escape from the island.)

‘The first night out’, continued Neave, ‘We found a deserted native village. The natives had all gone bush when the bombing started. We found a fowl, which we ate. We knew we were going to have a pretty tough trot. We had no food whatsoever, so we would have to rely on what we could get from the natives. Most of the natives were frightened of us. They knew if they helped us the Japanese would kill them.’

Later they found another village, where the natives cooked two fowls for them. On the second day, they found some disabled trucks with tins of food which had been punctured but they managed to salvage a few tins of bully beef. For about three weeks, the party trekked through the jungle, climbing mountains, descending into deep ravines and following precipitous jungle tracks from village to village.

Often, they went four or five days without a meal, relying only on what they could get from natives, or what the natives told them was edible in the jungle.

‘Word went ahead like wildfire that soldiers were coming’, Neave said. ‘To a black man, a soldier is a fighting man, and they expected us to come marching along with bands playing and all that sort of thing. But when we went begging for food our prestige went down flat.

Eventually we did what they said couldn’t be done – we crossed the Baining Mountains. On the south coast, we came to a place called Put Put – a sort of small Chinatown. I had dysentery very badly. There was a doctor there, but he told me he couldn’t do anything for me. There were two other Australians there and they were going to surrender. The doctor told me I should do the same. He said ‘You won’t live a fortnight’. I told him they said we couldn’t get across the Baining Mountains and we did, and that I’d be home for my birthday (July 19).’

They bought some rice at Put Put and then pressed on down the coast. Their only weapons were a sniper’s rifle with two or three rounds of ammunition and a revolver with two rounds. Eventually they came to Tol Plantation, the scene of one of the most infamous massacres of the war.

With thanks to The Herald Weekend 11 December 1976.

Part 2 can be found HERE