Where on Earth is Kundiawa?

Joy Benson • PART ONE

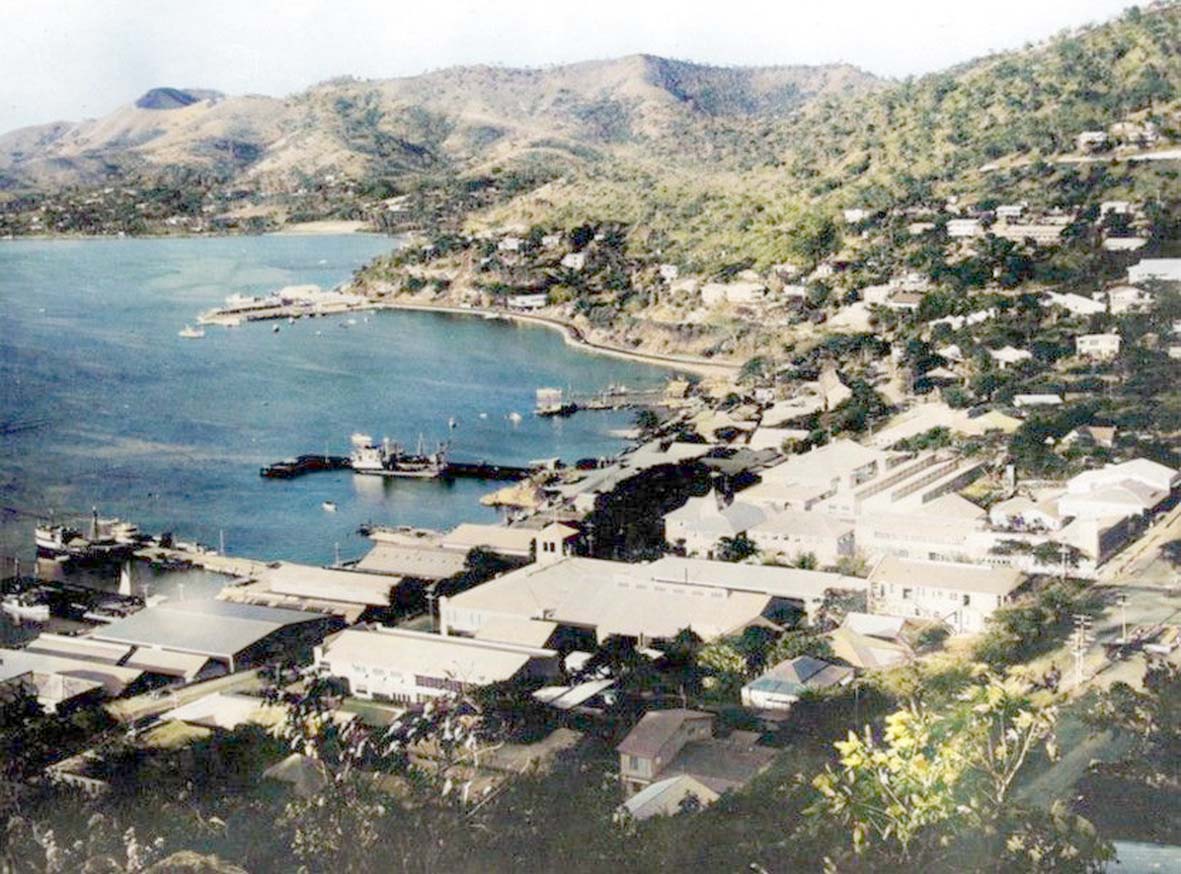

It’s 5 September 1967 and I’m winging my way to Port Moresby. Having not long completed a year of Midwifery training at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne following my General Nursing training at Charters Towers in North Queensland, I’ve been accepted into a position with the Public Health Department (PHD) in the Territory of Papua and New Guinea (TPNG). I know little of what awaits me, let alone that the 21-month term for which I signed up would become 10 years. Ten years of incredibly rewarding personal and professional experiences, with more than a few interesting challenges along the way.

I smile at the middle-aged man seated beside me on the aircraft, and we chat for a while. He asks why I am travelling to Port Moresby. When I tell him, he fixes me with a look of total disbelief and dismay. Didn’t I know about the dangerous people, the deadly diseases, the dreadful weather and numerous life-threatening situations I would face there? At first, I think he’s joking, but I quickly realise he is deadly serious. I can only stare back in utter confusion.

My relief at being on my way to TPNG has switched to despair, mostly over my naivety as well as annoyance at the stranger who, without invitation, has violated my private world.

Soon after take-off from Townsville, my fellow passenger, who boarded the aircraft in Sydney, falls asleep, leaving me to consider his words. As the Australian coastline disappears and the outline of the Great Barrier Reef gradually fades beneath the green sea, his warning words run riot in my mind. I’m no longer sure if the place and the job will live up to my expectations or whether it is I who will not live up to the expectations of the job and the place.

We are on approach into Port Moresby’s Jacksons airport when my neighbour wakes. He is good-natured but he can’t resist remonstrating with me again, telling me with a smile that if I had any sense I would catch the next plane home. His final and earnest words are, ‘There are two types of people in this Godforsaken place: missionaries and mercenaries. If you want to succeed, you need to decide where you fit.’ Retrieving his briefcase from the overhead luggage rack, he nods solemnly and walks quickly down the aisle to be first off the aircraft. I don’t see him again.

Humidity rolls in through the open aircraft doors, engulfing the cabin in a fog, and continues to weigh heavily on me as I cross the steaming tarmac. It’s hot, very hot! Overhead, enormous fans rotate lazily in a vain attempt to cool the huge space inside the terminal. Someone is supposed to meet me but I have no idea how I will recognise them in this crush of humanity. The chap on the plane might have a point, not only about life and work here but especially the bit about getting out of the country, fast!

I’ve never travelled overseas before and am surprised to pass through Customs quickly; there’s no need for an Australian passport, only an Entry Permit, because this is 1967, and TPNG is a Territory of Australia. I, being an employee of the Commonwealth Government probably makes things easier. Dragging (no trolley bags then!) my case along, I notice a local man holding up a handwritten sign with the letters ‘PHD’. After some moments it dawns on me—Public Health Department! A smiling Papua New Guinean grabs my bag and, in a flash, I am seated in a small four-wheel drive vehicle about to get my second impression of Papua New Guinea.

As I can’t see any buildings, I’m guessing we are nowhere near the city. In the distance a glowing chain of bushfires crown the Owen Stanley Ranges casting a pall of smoke over everything. As far as the eye can see, the environment is dry and dusty. Where is the green tropical island I envisaged?

As there’s little traffic, we drive quickly through silent streets. Is this all there is? A few people are walking along the road edges and my driver seems to know all of them. People wave to one another while my driver leans out the window shouting cheerful greetings, especially to the young girls! I feel totally overdressed in my pink linen suit and high heels!

In a cloud of dust we pull up in front of a low building partly obscured by greenery. A tangle of banana trees, bougainvillea, and frangipani crowd the entrance, almost hiding a long, low timber building. With the green painted concrete floor inside there’s an expansive and pleasant tropical feel about the place. Soon, I’m settling into a simple first-floor room with an overhead fan whirring dutifully above. I feel very alone.

The nurses’ home is situated in the grounds of Port Moresby General Hospital. Looking out through glass louvres, it’s hard to see anything resembling a hospital, but there are lovely views of hibiscus, frangipani and huge mango trees. Recalling my interview in Townsville, I know I will stay here for a few days while undergoing an orientation. Later, I will be posted to one of the many hospitals in PNG. There’s a slight chance I will remain at Port Moresby Hospital, but it’s unlikely as most double-certificated nurses are sent to the more remote centres.

After a pleasant evening meal with some friendly local nurses, followed by a restless night, I start work in a medical ward. The hospital is unlike any that I have experienced before. It consists of numerous low wooden single-storey buildings neatly arranged in rows that are connected by covered concrete walkways. At 7.00 am, inside the ward, I see a row of beds and curiously, in each, there are at least two people. Beside each bed, more people are sleeping on the floor with some even under the beds! I have one expatriate registered nurse and two local student nurses with me. I expect to wash and feed the patients to prepare them for the day. Very quickly it becomes obvious that I have a lot to learn.

This is the moment I first encounter the concept of ‘Territory time.’ I soon realise that I need to rid myself of the obsession of attempting to wash everyone and everything. Everything is done in Territory time. The first thing that our little group does is to make coffee when a couple of expatriate doctors turn up, joining the jovial coffee party. I also learn to drink very hot coffee laced with tinned evaporated milk in the tropical heat.

By 7.00 am, it’s hot and very humid. The uniform is clinging to my back and I still haven’t done any work. I feel guilty standing there when there are so many sick patients waiting, but I tell myself I need to learn to relax and go with the flow. Everyone else is relaxed and happy—doctors, nurses, patients and their wantoks, who I come to understand are the many relatives of each patient. All are now slowly waking and moving around outside, ladened with bamboo mats, blankets and cooking pots and looking for places to sit in the grounds. Everyone is relaxed. It’s up to me to divest myself of the urge to leap on patients and do things to them.

Generally, hospital patients receive wonderful care, but everything happens when and how they want it to . . . in Territory time. Unaware, my socialisation is well under way. I’m a fish out of water and yet everyone is welcoming and friendly especially the young student nurses who are a cheerful, giggling group. Their joy of life is infectious.

The Port Moresby Hospital spreads unfenced over a huge expanse of dry, dusty land. Along with the neatly lined-up rows of wards connected as they are by grey concrete pathways, other single-storey wooden buildings are scattered around as far as I can see. During the day the grounds are dotted with many groups of relatives and friends of the patients. Some stretch out on bamboo mats dozing under the trees, while others gather around large pots of food containing mainly rice, with what looks like fish stirred through it. Some people wash articles of clothing, then drape them over trees and rocks to dry, creating an overall sense of untidiness, but everyone seems happy enough as they chat, sipping tea from huge enamel mugs. No one seems to have jobs or chores to attend to—a vastly different scene from the manicured gardens of an Australian hospital.

I follow staff around most of the morning, trying to adjust my attitude and values to this land and its culture. Around midday, I return to the nurses’ home for lunch where I’m heartened to see a group of Australian women with piles of luggage being dropped off by the same dusty Land Rover that brought me the day before. I’m no longer the new girl! I feel a long way ahead of them, having been there about 18 hours, of which five hours were spent working. The new arrivals ply me with questions, most of which I can’t answer, but on returning to the ward I allow myself to feel like an old hand. Goodness knows why, because as I walk back I become lost.

With the new arrivals, there are now seven recruits. The other registered nurses (RNs) are from Adelaide, Melbourne and Brisbane. Lyn, from Brisbane, is upset because Qantas has lost her baggage, leaving her with nothing but hand luggage. Ruth, a girl from Adelaide, had two packs of playing cards confiscated as they are illegal in TPNG. Everyone is feeling a bit shellshocked especially given the overwhelming heat and humidity. We have arrived during the early buildup to the wet season, hence the dry, dusty environment. The next day we are sent to work in one of the many wards—our socialisation has begun in earnest.

Part Two of Joy’s story will continue in the next issue.