Volcanoes in the PNG Highlands

Colin Pain

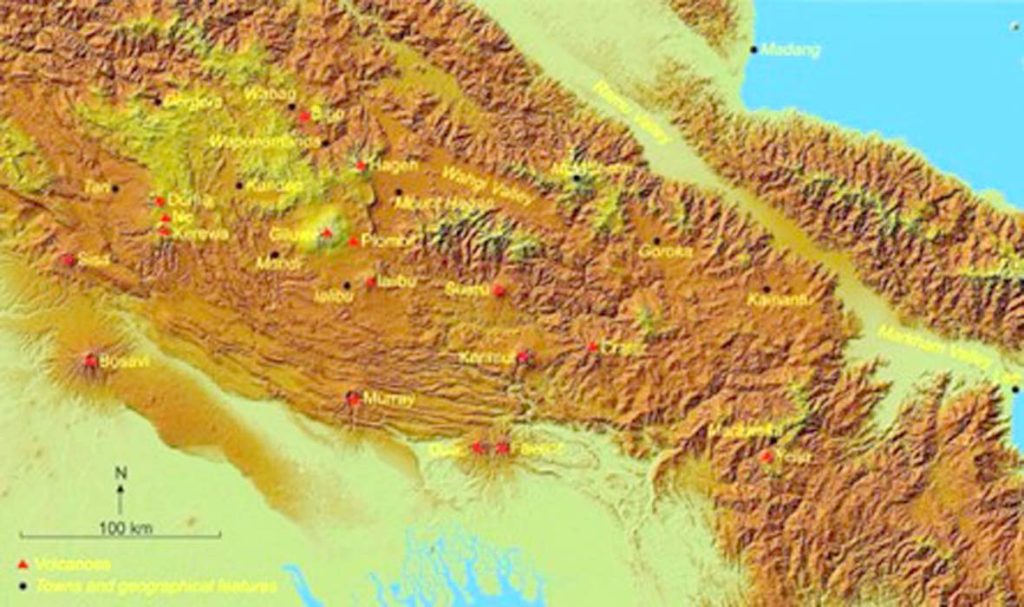

There are 15 large volcanoes and at least 30 small cones and craters in the PNG highlands. This map shows only the large volcanoes plus two cones that produced volcanic ash (Birip and Piombil) [Map compiled by Colin Pain with background image from the Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS), downloaded from OpenTopography]

It is well known that some mountains in the Papua New Guinea Highlands are extinct volcanoes, most having retained their original shape to some extent.

These volcanoes have an important impact on the Highlands. First there are obvious features in the landscape—Hagen, Giluwe, and Doma Peaks come to mind. Second, their influence extends for considerable distances away from their obvious landforms. I will talk about this extensive influence rather than the volcanoes themselves.

How many readers have travelled the roads in the PNG Highlands and wondered what the layers in the road cuttings are? I know I did. I spent a great deal of time spread over 25 years looking at road cuttings between Tari and the Kassam Pass, studying the materials they expose. The layers are volcanic ash, also called Tephra, an important product of volcanic eruptions. The area I studied, some 24,000 km2, has been covered by at least two metres of volcanic ash derived from the Highlands volcanoes. Over half that area has been covered by at least five metres, and in some places volcanic ash is more than 20 metres thick.

Hagen volcano from the Highlands Highway near Tomba – this was an important source of volcanic ash in the PNG Highlands (Photo: Colin Pain)

Volcanic ash beds are laid down very quickly in a geological instant. As they are deposited they mantle the landscape, distinguishing them from other deposits, such as river and lake beds, which are confined to lower parts. Why are they layered? Each layer represents an individual eruption or a series of eruptions, depending on how far away is the source volcano. Close to the volcano, each explosion may be represented by an individual shower bed. Further away the shower beds disappear and the layers are more uniform.

Individual volcanic ash beds can look very different from place to place. These differences are partly a consequence of the characteristics of the eruption. An important variation is the decreased bed thickness away from the source volcano. Ideally a volcanic ash bed would get thinner in all directions from its source. However, wind direction during an eruption controls changes in thickness away from the crater. Volcanic ash beds are usually present as elliptical deposits around a volcano, the axis orientation of each deposit dependent on the wind direction at the time of the eruption. In the Highlands, wind blows mainly from the east, so most of the volcanic ash goes to the west of the volcanoes.

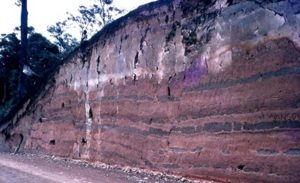

Layers of volcanic ash in a road cutting on the Highlands Highway near Togaba during construction in 1972—this road cutting exposes at least 20 metres of volcanic ash

When a volcano erupts, the cloud of volcanic ash is made up of large, medium and fine particles. Larger and heavier grains fall faster than light ones, so individual volcanic ash beds close to a volcano may grade upward from coarse to fine. The same happens with distance from a volcano. As an ash cloud spreads, coarser particles fall out close to the volcano, while further away only fine particles are deposited. Associated with a decrease in grain size is a decrease in the number of beds derived from an eruptive source that can be recognised with distance from that source. Two volcanic ash beds identified near the source may be recognisable as only one further away.

The same applies to the thickness of ash beds with distance from the volcano—deposits become thinner with distance. It is also common for shower beds from individual explosions to be present near a volcano and absent further away. With distance from a volcano, ash beds become more uniform. This means that an ash bed close to a volcano may represent one explosive event, whereas a bed further from a volcano may represent many explosive events.

Layers of volcanic ash in a road cutting on

the Highlands Highway near Paigona in 1975—the thin dark grey layers are the sandy basal parts of shower beds—further away from the volcano the sandy layers disappear and the beds become finer and more uniform

Relatively short eruptive periods are usually followed by long periods of quiet, during which vegetation is established and soil formed on the deposited volcanic ash. In major eruptions where the resulting deposits are thick, new soil is formed on a sterile surface well separated from the old soil, which is now buried and sealed off. At greater distances from the source, where volcanic ash beds are thinner, they cause little disturbance to vegetation and become incorporated into existing soil. Where this occurs, it may be difficult or impossible to identify individual beds.

Buried soils, present over wide areas, are good for the identification and correlation of volcanic ash beds. Where deeply buried they lack organic staining but may be a different colour from the main part of the ash bed. Buried soils show that there was a quiet period between the eruptions long enough for soil to develop. This period is likely to be hundreds if not thousands of years.

Assisted by my colleague Russell Blong, I was able to identify 18 different volcanic ash layers spread across various parts of the Highlands. How do we know which layer is which? Stratigraphic position, the order in which the layers are found on the surface, provides relative age. Properties such as colour and particle size are the main criteria for recognising the different layers. Volcanic ash units were identified and described by ‘hand-over-hand’ mapping. This meant going from road cutting to road cutting (separated by hundreds to thousands of metres), following the layers using their stratigraphic position and other properties to recognise them. Characteristics such as colour, particle size, and the presence of buried soils, coarse basal layers, and shower bedding change across the distribution of a volcanic ash layer, whilst hand-over-hand mapping allows individual units to be followed for considerable distances, even if they change their character. The work thus relied almost entirely on the presence of road cuttings, and for this reason I give heartfelt thanks to anyone who has made, or caused to be made, roads in the PNG Highlands (despite the nerve-shattering experiences I had while negotiating some of them).

Layers of volcanic ash mantling old

landscapes in a road cutting near Tambul on the

road to Mendi in 1970—there are two buried

soils, the upper one expressed as a groove in the road cutting and the lower one as light-coloured blocky material—they demonstrate that there were hundreds to thousands of years between the eruptions that produced the volcanic ashes. (Photos: Colin Pain)

How far are the volcanic ashes spread? I mapped from Tari in the west to the Kassam Pass in the east. I estimate that at least 75,000 square kilometres of Highland PNG received more than 50 centimetres of Tephra from various Highland sources. The total volume would have been well over 300 cubic kilometres. A lot of this has now been eroded and removed from the Highlands.

Where did the volcanic ashes come from? They came mainly from Giluwe and Hagen in the west and Yelia in the east. Birip cone also produced ash that reached as far as Kandep. The youngest major volcanic ash layer in the Highlands is Tomba Tephra which erupted from Hagen volcano at least 200,000, and possibly as much as 400,000, years ago. It would have been about the same size as the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, the second-largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

Apart from their scientific interest, volcanic ash layers are important for the PNG Highlands for two main reasons:

First, land use in the Highlands is important for planning purposes. Highland soils are dominated by humic, yellow-brown clay soils formed on volcanic ash that support large agricultural populations. Volcanic deposits have covered thousands of square kilometres, and thus soil parent materials are uniform over large areas.

Second, slope stability is an important consideration for earthworks, including roads, dams and mining activities. The presence of volcanic ash on steep hillslopes allows the stability of individual sites to be assessed in a long-term sense despite the range of geomorphic environments and the natural variability of the lithology. A hillslope covered with volcanic ash that has been stable for more than 200,000 years at a slope of 20 degrees can be expected to remain stable at that angle. On the other hand, hillslopes that have lost volcanic ash cover are likely to be less stable.

So, there is a widespread cover of volcanic ash in the PNG Highlands. We estimate that at least 120,000 square kilometres received more than 50 centimetres of volcanic ash from various Highland sources, meaning that all the Highland provinces, as well as the Highland areas of Western (Fly), Sandaun (West Sepik) and East Sepik Provinces, received large thicknesses of volcanic ash. Thin deposits less than 50 centimetres thick likely extend into the Indonesian side of the island. Moreover, many Highland volcanoes (e.g. Bosavi) have not been studied as sources of volcanic ash. There is also a much wider road network now than there was when I carried out my work; there is plenty left for the next generation of volcanic ash followers.

Detailed results can be downloaded HERE.