VALES & TRIBUTES

COLLIS | KAUAGE | VICKERS | ALPERS | MARCHMENT | LEPANI

COLLIS, Norma

23 January 2025

Norma married Ted Collis in 1954 in Forbes, NSW, while Ted was enjoying six months’ leave from the Territory of PNG (TPNG). After Ted’s leave, Norma travelled to PNG with Ted as a new bride to the Territory. She lived at the Yalu Department of Forests sawmill until 1960 when Ted moved to Lae to work in the government sawmill. Their daughter Cheryl and son Greg were born in Lae in 1955 and 1956.

When the Lae sawmill closed in 1962 and became the Lae market, Ted and Norma, with their family, moved to Bulolo where Ted became the manager of the TPNG Forests Nursery.

In 1964 Norma began working at the Bulolo Forestry College under principal, Joe Havel. Norma was Joe’s first clerical assistant, working at the college for nine years. The college’s students with a grade 10 education came from Laos, Tonga, Fiji, Samoa and PNG.

The establishment of the Bulolo Forestry College in 1962 saw the commencement of formal technical training for Papua New Guineans. Initially, training entailed a two-year certificate course. A three-year diploma course was introduced in 1967, with the first graduates commencing their fieldwork in 1970. Albert Kairo was the college’s first Papua New Guinean lecturer appointed under Joe Havel. Bulolo Forestry College’s first principal was Joe Havel, followed by Bill Finlayson, then Leon Clifford, Robin Angus, and later, John Godlee.

In 1974 Norma moved to the forest station where she was employed as a pay officer under District Forester, Dick McCarthy. Norma gave so much for the PNG Forestry students in Bulolo from 1964 to 1975 when in December of 1975, she and Ted retired to Bribie Island in Queensland.

News of Norma’s passing came from her daughter, Cheryl Collis.

Richard McCarthy

KAUAGE, Elisabet

5 February 2025

Papua New Guinea lost a national treasure with the passing of renowned artist Elisabet Kauage, following a short illness. Elisabet was born in Kambu, Kerowagi District, Chimbu Province in 1958. She moved to Port Moresby in 1983 and commenced painting in 1986. Elisabet was self-taught, learning by observing her late husband, Mathius Kauage, draw and paint. Mathius was a pioneer of Papua New Guinea’s contemporary art movement.

During the 1990s Elisabet regularly attended weekend craft markets held in the grounds of Ela Murray International School at Port Moresby’s Ela Beach, where she sold her paintings alongside her late husband and fellow self-taught artists, such as the late John Siune and Oscar Towa. This she did while keeping a close eye on her growing children.

Elisabet’s detailed observations of everyday life and interactions among her fellow citizens and PNG’s expatriate community provided rich and endless subject matter for her artworks. Her exuberant paintings in the naive style, which typically featured political narratives, Bible stories and characters grasping new technologies, form a wonderful socioeconomic record of everyday life in Papua New Guinea.

Various exhibitions of Elisabet’s artwork in Australia, England, Germany, Italy and elsewhere overseas during the past 30 years throw a spotlight on contemporary art in PNG. She inspired many talented women lacking formal education in PNG and the wider Pacific region to pursue visual arts as a career.

In her later years, Elisabet could be found selling her paintings outside the Holiday Inn in Hohola, or at various other craft markets around the city of Port Moresby, dispensing wisdom and leaving a calming influence in her wake. Despite her shy façade, an aura of warmth and hospitality defined Elisabet’s personality as the unofficial matriarch of PNG’s contemporary art movement.

Elisabet’s sons, Chris, Andrew, John, Willey and Michael, have also forged careers as artists, but not her three daughters. Elisabet was the only female in her family to take up the brush.

Her enduring legacy lies in her artworks which can be found hanging in private homes and prestigious galleries around the world, including Queensland’s State Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane and the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Her work brings joy, colour and vibrancy to the lives of everyone privileged to view her paintings.

Hers was a long and productive life. Vale Elisabet. Mi paint—em tasol.

Don Wotton

VICKERS, Dr Wesley

6 May 2022

Wes Vickers was exceptional even at a young age. Born in Brisbane 27 August 1937, Wes spent his young life in various locations across QLD and NSW to which his parents’, Harold and Gladys Vickers, Salvation Army ministry placements, took them. Wes was also an accomplished musician, playing the piano, the organ, the flute, guitar and recorder, gaining high qualifications in performance and theory. He was an avid reader, this leading him towards a future as a doctor in overseas countries through reading the teachings and reverence for life of Dr Albert Schweitzer.

After two years as a boarder at Scots College in Warwick, Wes began medical studies at the University of Queensland. In his third year, a cadetship with the Department of Territories offered by the then Director of the Department of Health in Papua New Guinea, Dr Roy Scragg, enabled him to plan his life and begin his journey to PNG.

As part of the cadetship, Wes accumulated a knowledge of Papua New Guinea’s medical needs by spending his 1960 and 1961 Christmas university vacations in Port Moresby, Mt Hagen and the Eastern Highlands. Recognising a future lack of laboratory support in remote locations, Wes took an additional year during medical school to complete a Bachelor of Science and buy his own microscope and many medical instruments in the areas of ophthalmology, paediatrics and obstetrics.

His letters home, descriptive and full of excitement, described Mt Hagen Hospital as constructed from bush materials, just three wards and an administration area. Patients were often moved outside for ward rounds where the air was fresh. Dr Vladas Ivinskis, a Lithuanian, was the sole medical officer for a population of 320,000. In one letter Wes described an experience of a retrieval team to the crash site of a Norseman and collecting body parts in butter boxes.

Wes and his wife were married in Sydney in early 1963 in his father’s church at Neutral Bay, flying to Hobart the next day so Wes could complete a year of Medical Residency at The Royal Hobart Hospital. Their next move was the big one to PNG, arriving with a ten-week-old baby son, David, and three suitcases.

Wes’s first posting was as a medical officer at Bogia in Madang District, an outstation 13 kilometres from Manam Island, with its two active summit craters and frequent mild to moderate eruptions. Wes was in his element! He patrolled in remote areas sometimes with District Officer Peter Sheekey and a police escort along with medical and personal supplies packed in tin trunks slung under wooden poles carried by villagers. They slept in kunai haus kiaps, and at times they used dugout canoes with outboard motors to move along crocodile-infested waterways, usually accompanied by Casey, the Irish Terrier Wes inherited from a dying copra plantation manager, Claude Rouse.

Other duties included visits to mission stations to foster good relationships and to check on their needs for the administration. Wes immunised children, overnighted at remote aid posts, missions and plantations, conducted clinics, checked on spleen sizes for malaria, and looked after any inpatients at Bogia. When on patrol, messages would be relayed via the outstation two-way radio or by a villager bringing back a letter.

Manam Island was the site for Wes’s first exhumation and autopsy, carried out under the coconut palms and watched by hushed and curious onlookers, all with handkerchiefs tied tightly around their noses. This day was one of so many memorable and unusual days in the life of an outstation doctor.

At Bogia the hospital mainly provided outpatient services with the occasional emergency surgery. Sister Gwen Sheekey ran the Infant Welfare clinics and delivered more babies there in 1964 than Madang Hospital did. Gwen, the widow of Peter Sheekey, now lives in Sydney.

Wes was asked to move into Madang shortly after being summoned there to give evidence at a Supreme Court murder trial. This was a change from outstation life. His duties were now in wards and the operating theatre, delivering babies, plus hospital governance in his role of Superintendent of Madang Hospital. Wes also started sailing on Madang Harbour as regularly as he could.

In 1966, after the Department of Health accepted Wes’s request to further his postgraduate studies in Public Health at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, he fell ill with malaria. This made him a curiosity for the local General Practitioner and University hospital staff. No one could remember when they had seen a patient with malaria, let alone a doctor who had forgotten to take his antimalarial drugs.

A new PNG posting followed, to Mendi, a settlement in the Southern Highlands of PNG laid out around the airstrip. From here Wes administered 12 much smaller outstations with aid posts, and small hospitals in Tari and Ialibu, accessed mostly by air with some Land Rover travel.

Their daughter Sue was born in Goroka in March 1967. They lived close to Mendi Hospital, rather than as part of the hospital compounds in Bogia and Madang.

During the Mendi posting, in addition to ward rounds, some surgery and clinics, Wes went to district and regional meetings, with the big push for the road south to Kikori being one of the projects he worked on with other Heads of Department. Wes prepared papers for the World Health Organisation and the World Bank, and I recall his mind literally buzzed with ideas and planning on how to take PNG and the Southern Highlands ahead. Medicine was only ever one part of his life and thinking. There was always a big picture.

In 1969, after two years in Mendi, Wes undertook further postgraduate study, this time in Edinburgh, United Kingdom, and was back in Mendi mid-December. On arrival, Wes was met by a senior army officer and flown to various locations to assess major crises. The Southern Highlands was in the grip of a famine, and a deadly influenza outbreak had already claimed over 2,000 lives. Wes moved quickly from one mode to the next with his medical duties always given top priority.

In April 1972 Wes made a difficult personal and family decision to resign from the department and return to Australia. The news came as a shock to the Director of Public Health in Port Moresby, Dr William (Bill) Symes, who wrote:

As a health administrator, Dr Vickers excelled in planning, organisation, personnel management, appraisal and evaluation. He accepted responsibility and made decisions. His professional judgement was excellent and characterised by objectivity and a careful appraisal of the situation as a whole. No one could question his motivation and dedication to his professional tasks … or his ability to work with people.

Dr Vickers’ resignation, despite offers of promotion, was a blow to the Department of Public Health. Few doctors of the calibre and personal and professional maturity of Dr Vickers come to work as health administrators in this country.

The years of service in PNG laid strong foundations for what followed. Wes distinguished himself in senior leadership positions with the Health Commission and Department of Health in the NSW Government, working in major health regions—the Hunter, the Illawarra, the Southern Highlands, and Southern Region. Then, when most doctors might have been thinking of retirement, Wes reevaluated his priorities, retrained and worked in Accident and Emergency, then as a GP part time and a career medical officer in a private hospital. He found the move back to face-to-face medicine rewarding.

Medicine and music weren’t Wes’s only passions. He very much enjoyed quality family time, sailing on Lake Macquarie, obtaining a PADI diving certification, completing a welding course, honing his photographic skills, and breeding and showing Irish Terriers (all related to Casey in PNG). Wes was also a Deputy Rural Fire Captain. He enjoyed a wonderful 16 years on the farm near Robertson in the NSW Southern Highlands where he bred Angus cattle—being a country boy at heart. During those years, Wes also provided mentoring and stability for two young men, Peter and Trent who joined their family.

Cognitive decline led to Wes’s moving into residential care for five years, a Memory Support Unit at Frederickton, just outside Kempsey. Wes adapted to the move, mostly believing he worked there. The staff kept a ‘special folder of work’ clearly marked ‘Urgent Attention Dr Vickers’. Wes also played the flute and a recorder with the music team during those years.

Wes died seven weeks after being diagnosed with an aggressive head and neck cancer. Mercifully, he did not know about his medical situation, maintaining a positive and mostly happy disposition in difficult circumstances, usually with an engaging smile.

Many stories were shared by family and friends who travelled from far and wide to Wes’s Farewell Celebration in Port Macquarie. Son David, who has lived in Hawaii for 38 years, spoke at the celebration and recalled several PNG anecdotes. Sadly, their daughter Sue died in 2016. Her death was a deep loss for Wes, as it was for the whole family.

Wes’s casket was woven from banana and pandanus leaves with a stunning wreath of orchids, Bird of Paradise blooms and ferns. He would have approved as this completed the circle back to PNG. Wes would have also agreed with the words of the Nobel Laureate Tagore that ended the Celebration.

‘Farewell my friends, it was beautiful as long as it lasted—the journey of my life.’

Bron Vickers

ALPERS, Prof. Michael

3 Dec 2024

The PNG Kundu published an article in the March issue titled ‘In Memoriam: Emeritus Professor Michael Alpers AO, CSM, FRS, FAA which can be found HERE.

The following is a corrigendum prepared by Dr Deborah Lehmann AO, Honorary Emeritus Fellow, The Kids Research Institute Australia and Dr Deryn Alpers, Senior Lecturer, Murdoch University.

Corrigendum

As Michael’s partner, we were fortunate to have had a wonderful life together for 40 years, sharing everything on a personal and professional level. Deryn Alpers is Michael’s daughter. Thank you for publishing the article reporting on Michael’s funeral and honouring his enormous contribution to humanity. We wish to clarify a few points with some additional comments.

As Michael’s partner, we were fortunate to have had a wonderful life together for 40 years, sharing everything on a personal and professional level. Deryn Alpers is Michael’s daughter. Thank you for publishing the article reporting on Michael’s funeral and honouring his enormous contribution to humanity. We wish to clarify a few points with some additional comments.

Michael was born in Adelaide on 21 August 1934 and died peacefully in Perth on 3 December 2024 at the age of 90. Among his many accolades Michael was a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Companion of the Star of Melanesia.

The funeral was a celebration of Michael’s extraordinary life, a joyous occasion for a long life well lived, tinged with sadness at the loss of such a humble, compassionate human being and eminent scientist. The funeral was followed by a natural burial. At least 200 people attended the funeral, and we were informed by the funeral directors that at least 200 people attended online. The 10 Papua New Guineans who attended the funeral were:

- Dame Meg Taylor, a close friend of Michael’s, as were her late father, the explorer Jim Taylor, her late mother, Yerima Manamp and her sister Daisy Taylor;

- Igitava (Igi) Yoviga, a member of our extended family who identifies as Michael’s son/nephew from a customary perspective;

- Professor William (Willie) Pomat, the current Director of the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR), a mentee of Michael’s up to the time of his death; Meg, Igi and Willie paid tribute to Michael during the funeral service.

- Ms Norries Pomat, Willie’s wife and a longstanding PNGIMR staff member who worked very closely with Michael;

- Professor Sir Isi Kevau, Professor of Medicine at the University of PNG and Chair of the PNGIMR Council;

- Alpers Willie, a member of our extended family;

- Norman Javati, representing his family, who have both personal and professional connections with Michael and PNGIMR;

- Lydia (who recently completed a PhD at Curtin University) and Joachim Kuman;

- Mary Robinson, a Papua New Guinean friend residing in Perth.

There were also tributes from Michael’s niece Sarah Alpers, Professor John Mathews, an eminent epidemiologist, Founding Director of the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin and close friend who worked with Michael on kuru, and Professor Fiona Stanley, whose family has been a longstanding close friend of our’s. Fiona’s grandfather, Evan R Stanley, was the first government geologist in the Australian Territory of Papua. Fiona went to PNG as a medical student and later had links with PNGIMR while Director of the Telethon Kids Institute (now The Kids Research Institute of Australia). She was also Chair of the PNGIMR Buttressing Coalition for two years. Michael worked closely with Fiona’s father, Neville F Stanley, Foundation Professor in Microbiology at the University of Western Australia.

There were also tributes from Michael’s niece Sarah Alpers, Professor John Mathews, an eminent epidemiologist, Founding Director of the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin and close friend who worked with Michael on kuru, and Professor Fiona Stanley, whose family has been a longstanding close friend of our’s. Fiona’s grandfather, Evan R Stanley, was the first government geologist in the Australian Territory of Papua. Fiona went to PNG as a medical student and later had links with PNGIMR while Director of the Telethon Kids Institute (now The Kids Research Institute of Australia). She was also Chair of the PNGIMR Buttressing Coalition for two years. Michael worked closely with Fiona’s father, Neville F Stanley, Foundation Professor in Microbiology at the University of Western Australia.

In 1999 Michael established the PNGIMR Buttressing Coalition, an interactive coalition that is committed to supporting the PNGIMR without jeopardising its integrity, a model for the conduct of collaborative research globally. He also facilitated the establishment of the unique Melanesian Film Archive at Curtin University. Michael mentored many people worldwide, as evidenced by the hundreds of messages we received after his death.

Dr Deborah Lehmann AO and Dr Deryn Alpers

Isobel Mary Marchment—A Remarkable Life

17 February 1921–16 January 2025

Part One: Isobel Marchment wrote a memoir for her 100th birthday.

For this tribute I referred to her notes to add to my own anecdotes and memories.

Peter Comerford

Isobel Marchment at her desk at Madina Girls High School in New

Ireland, 1972 (photo by Gordon Doyle)

The remarkable life of Isobel Marchment began on 17 February 1921 in Wiltshire, England at Charlton Park on the estate of the 19th Earl of Suffolk and Berkshire, where her mother, Mary Crowther, worked in the dairy and her father, David Marchant, a returned soldier, was a gardener. The couple married in 1915 and had two children, David and Isobel.

It has been said Isobel inherited her determination from her mother and that she was quite adventurous from an early age, prone to wandering and exploring. Village people often were sent the message that if they saw that little Marchment girl they were to take her home. When she was older, the family moved to another large estate, Winterfold, where her father was head gardener. At 5 pm each evening, Mary would blow a whistle, signalling Isobel to stop her wanderings and games and scurry home.

Isobel contracted glandular tuberculosis in her neck when she was ten years old, an illness that later led to hospitalisation and hampered her chances of winning a scholarship for secondary school. A combination of her mother’s determination and the help of David, her older brother, who coached Isobel every night, Isobel passed the entrance examination and began high school in September 1932, later becoming school captain and matriculating.

By 1939 many men were about to enlist just as WWII broke out. This created a shortage of teachers, so Isobel set her eyes on teaching. In 1939 she was accepted into teacher training at Bishop Otter Memorial College in Chichester, Sussex.

As Hitler’s armies pushed through Europe, conquering countries in their path and the invasion of Britain was imminent, Isobel, along with other college students, slept in air raid shelters at night. She recalls the college being strategically in a bad position with an RAF base on one side at Thorney Island and on the other the Tangmere Spitfire base where the war hero, Douglas (Tin Legs Bader) Bader, was in charge.

Isobel’s parents in the meantime had moved to the Isle of Wight as Winterfold House was appropriated as a Special Operations Training School for undercover agents heading for German occupied France. One of the agents was Violette Szabo who was awarded the George Cross and was the hero of the book and film ‘Carve Her Name with Pride’. When Isobel was headmistress at Madina Girls High School in New Ireland, she often showed the film to the students. It obviously affected her to the extent that she used it as a teaching tool for character-building for female students.

Memories of Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain and The Blitz, and the soldiers going away to war remained with Isobel, memories she often shared with students and staff. In 1971 while she was headmistress at Madina, a loud explosion rocked the staffroom. Sitting in her office and visibly shaken, she announced, ‘That was a bomb! I will never forget the sound of them.’

Investigations revealed that village women working in their gardens behind the school had found a bomb while digging in their garden to plant sweet potatoes. They handled the discovery in a basic village way by piling wood onto the bomb and lighting a bonfire. The women then retreated to sit under a tree and smoke their brus tobacco and chew betel nut while waiting for the bomb to explode, which it eventually did. Earth and rocks were blasted everywhere leaving a huge smoking crater in the ground. Miraculously no one was killed or injured.

During WWII Isobel’s parents lived in a house that faced Portsmouth and Southampton. German planes in their hundreds would fly right over them to bomb those locations and continue on to bomb London. While staying with her parents, Isobel recalled the battles overhead and running out of the house when a plane with the German swastika flew so low over her head before crashing and bursting into flame in their orchard, so low she clearly saw the pilot’s face.

Isobel moved to Devonshire when it was swarming with American troops training to join the British soldiers in the invasion of France, in 1943. She fell in love with an American medic but sadly, after the D-Day Landings, she never heard from him again.

After the war ended, Isobel left England to take up a teaching position at St Margaret’s College in Christchurch, New Zealand. It was there she met her lifelong friend and travelling companion, Frances Morris. Isobel followed Frances to Australia and spent some time travelling and working in part-time jobs around Queensland before finding a teaching position at Ascham, an elite independent girls’ school in Sydney.

After leaving Ascham, Isobel sailed back to England with Frances, spending time with her parents in the Lake District before taking up teaching jobs in London.

The desire to travel was strong, so in 1952, both Isobel and Frances applied for teaching positions in Newfoundland. Following a year in Newfoundland, the two women travelled to the USA and Canada, buying push bikes to continue their adventures. They heeded the warnings in the Rocky Mountains about bears and moose and survived several encounters along the way. There were many highlights, and cycling through the Grand Canyon was one of them.

Shortly after returning to England, Isobel’s father died, prompting a move back into the family home to nurse her mother until her passing in 1955. Meanwhile, Frances Morris returned to Australia following her mother’s death.

To be continued in the next PNG Kundu issue

A TRIBUTE BY ANDREA WILLIAMS

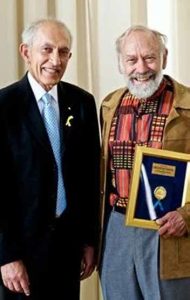

Sir Charles Watson Lepani KBE, CBE, OBE

28 October 1947–10 January 2025

PART TWO: In its earlier tribute to one of its greatest supporters, Sir Charles Lepani, following his passing on 10 January 2025, the Papua New Guinea Association of Australia (PNGAA) highlighted some of Sir Charles’s important contributions to the Association. This second section focuses on his young life, his outstanding career and the remarkable achievements that followed.

Sir Charles’s homeland in PNG is the Trobriand Islands, where his grandfather was the chief of Vakuta Village. His mother was Sarah. His father, Lepani Watson, was one of only two village lads allowed a mission education. He believed greatly in hard work, a philosophy he instilled in his son, Charles. Lepani Watson eventually moved to Port Moresby, becoming a clerk in the Department of Treasury, and with his family he lived next to Sir John Guise’s family in Kaugere. Later, he was elected as the representative for the Trobriand Islands in PNG’s Legislative Council.

Lepani Watson was significant in both the administration and in his Hohola neighbourhood. His grassroots campaign to win the election was dissected in an influential study by distinguished anthropologist Peter Lawrence, whose book about that campaign was later used by Sir Ebia Olewale as a primer, a how-to-do-it, for his own campaign to win a seat in the House of Assembly for the PANGU Pati. Sir Charles’s father was a widely loved, humble man, as was his son.

Growing up among early Methodist (now United Church) missionaries and living under Australia’s administration of PNG had an enormous impact, both positive and negative, on Charles Lepani. It gave him great respect for authority and the law and also how one can adapt through culture as well as what life can bring.

As a young lad, Sir Charles was one of the top 20 primary school students in the country when he was awarded an Australian government scholarship that led to furthering his education in 1961 in Charters Towers, Queensland. At the time, Lepani Watson said to his son, ‘This is the opportunity. Don’t let it slip. Be the first in line, be the first, be the first to have worked. Be the first to line up for this.’

Reminiscing on travelling to Australia, Sir Charles told Jonathan Ritchie in July 2011:

When we landed, I was astounded to see white people doing manual jobs … And I was frightened … who was going to take my luggage off my plane and put the stairs down so I could walk off? … Everybody walked off and this air hostess kind of came and said to me, “This is where the flight ends. That’s where you get off.”

I said, ‘But who’s…? How am I going to get off and step on these stairs when white people have put the stairs down, and my luggage? Am I going to…?’

She said, “No, no, no, no. They’ll bring your luggage. You go. You get out.”…That was the first eyeopener, seeing white people doing manual jobs. Never seen them in PNG. I was stunned…I got off, waiting for the police to come and arrest me because…I’m a black person getting on the stairs…my luggage was being collected by white people. So that…sticks out in my mind [and was] the de-colonisation of my mind in a sense.

And the high school in Charters Towers was another…it’s a milestone for me. It made me who I am.

As Sir Charles said, in Charters Towers he made many lifelong friends at school and came to understand how being good at both schoolwork and sports earned him respect. He was welcomed into the homes of local families, on farms and on cattle and sheep stations which was when he learned to ride a horse.

It was timely that the University of PNG (UPNG) took in its first cohort in 1966 as Sir Charles’s schooling in Charters Towers came to an end the following year. This saw him return to PNG and enrol in UPNG. After two years, he earned a scholarship awarded by the ACTU and the Papua New Guinea Public Service Association (PSA) to attend the University of New South Wales. According to distinguished PNGAA colleague Paul Munro AM, ‘the eminent industrial relations academic, the always colourful Professor Bill Ford shared fond memories of Charles as his energetic and engaging young student on the Kensington campus and surrounds.’ With PNG’s transition to self-government from 1971 to 1973, the PSA suggested Sir Charles should complete his university studies in PNG.

Sir Charles became one of the country’s highest ranked civil servants during PNG’s decentralisation process from self-government in 1973 through to independence in 1975, being appointed Director of the PNG National Planning Office from 1975 to 1980. This saw him having tight control and management of fiscal policy at 27 years of age. Sir Charles, along with Rabbie Namaliu as Chairman of the Public Service Commission, who was decentralising the public service; Mekere Morauta in Finance, who was dealing with fund decentralisation; and Anthony (Tony) Siaguru, who headed Foreign Affairs, together they earned notoriety as the ‘Gang of Four.’ Nothing went through Cabinet without them.

Sir Charles considered his role in nation building and the period from PNG self-government to independence in 1975 as a highlight in his life. The feeling of enthusiasm and sense of excitement were unique, perhaps coming close to, ‘when you talk to some expatriate kiaps; those who go out in the jungles, take patrols—that sense of nation building. For us—it’s independence.’ Thus, when Sir Charles met Australian kiaps through the PNGAA and whilst living in Canberra as PNG High Commissioner to Australia, he encouraged them to write their stories. ‘What you did is part of our history; it’s important that you put it in writing for future generations, both Papua New Guineans and Australians, to learn how PNG came to be what it is today.’

Sir Charles was always keen on ongoing discussions about PNG. He believed it was the right of Australians to do this, ‘because today’s PNG is your creation also.’

Sir Charles’s role as head of the PNG National Planning Office saw him being involved in the formulation of PNG’s post-independence macroeconomic policy and public sector planning system, including aid coordination. He said, ‘… the team was amazing. And the air of what it is together to build a young nation: white and young Papua New Guineans coming out with first degrees and no experience. But having to run an organisation with the support of young expatriates.’

After five or six years in the Planning Office, Sir Charles went to the United States to study for a Master of Public Administration (MPA) at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. After returning to PNG, he ran his own consultancy business for eight years whilst also starting a family. Sir Charles was one of the first two Papua New Guinean freelance consultants working in the private sector, gaining valuable experience in surviving in challenging circumstances. He was eventually contracted by the Australian and PNG governments including PNG’s provincial governments.

In 1986 Sir Charles was invited to lead the Pacific Islands Research Program (PIRP), which he did for five years. He noted that this experience was a great opportunity to get to know the Pacific Islands. Having served as PNG’s Ambassador to the European Union from 1991 to 1994, Sir Charles was one of PNG’s most experienced diplomats,

On his return to PNG, Sir Charles ran the Minerals Resources Development Company, established in 1975, initially to acquire state-owned and landowner equity interests in mining and petroleum projects and to manage the equity funds for landowner companies from the major resource development areas of PNG. He ‘was stunned to see [that PNG was] living in debt, getting money from joint venture partners to finance our equity.’

From his time in National Planning, Sir Charles understood the importance of fiscal self-reliance for an independent country. He firmly believed that PNG could and should benefit from its assets, a vision that drove the next five years of his work with the aim of reducing Australian aid. These groundbreaking negotiations were challenged by the breaking news of the ‘Sandline Affair’. Sir Charles needed to convince international investors of the stability of the country, that PNG was a constitutional democracy and that a commission would get to the bottom of ‘Sandline’.

Sir Charles’s final roles were as Director-General of the 2018 APEC Authority in Port Moresby and more recently, Chair of the Eminent Persons Group that worked on the Foreign Policy White Paper.

Sir Charles had a lifelong passion and dedication to his country and its people, as well as a strong belief in the Australian-PNG relationship. He represented PNG internationally and domestically with great distinction. The development of a common national identity for PNG will be his enduring legacy.

With grateful thanks to an interview of Charles Lepani conducted by Jonathon Ritchie on 13 July 2011 for the Oral History and Folklore Collection conducted by the National Library of Australia. Available online at https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-220254691/listen

Part ONE can be found HERE.