The Strange World of Lae, New Guinea in 1962

Ann Mallard

I went to Lae to get married. My new husband, Ken Mallard, was an Australian I met on a ship returning from my first trip abroad. Neither of us had families who were placed to host a wedding, so we got married in Lae where Ken worked for the Australian Government in Forestry.

Home was a two-bedroom flat above Kam Hong’s in downtown Lae. Ken had hoped to get a government house but there were none available. Our new home was big but very empty. Somehow I had finished a few curtains on a borrowed machine before the wedding, so we had a little privacy. But there was no furniture besides the bed! The flat did have hot and cold water (unlike the single dongas in town where Ken had lived for his first two years in Lae—they were cold water only).

In those days the town was very small. The population was mostly made up of Europeans— expatriates from Australia and a few (mostly missionaries) from Germany or the US. I remember going to the main shop in town and, when I got to the counter, the expatriate clerk on hearing my American accent would say: ‘Shall I book this to the Lutheran Mission or the Seventh Day Adventists?’

I would say with dignity: ‘I’m an ordinary American, not a missionary!’ and take out my money.

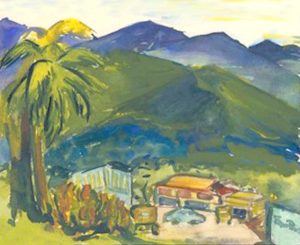

The town sat on a plateau between the sea and the huge green mountains covered with jungle. The shopping area was one block long and the only real European-style store was Burns Philp (BP’s we called it), an old-fashioned general store with a bit of everything from groceries to hardware and clothing—but never, it seemed, the bit you wanted!

Burns Philp is in the far-right corner of my sketch of Lae, which I did soon after we settled in. The brown buildings in the centre are the government offices because Lae was the administrative capital of Morobe Province. This sketch is hardly photographically correct, but I was trying to dramatise the small size of the town against the mountainous hinterland.

Down the block from BP’s was the movie theatre showing movies once a week. All along the sidewalk at the BP’s corner were street sellers, often selling beads.

Around the corner from BP’s was Kam Hong’s, a Chinese trade store selling an odd collection of tinned fish and other staples that the local people would buy, and all sorts of exotic imports from Asia—like the magnificently carved tea chest we bought right after we got married because we had no place to put anything, or inexpensive batik cloth which I learned to sew into loose dresses (mumus).

Besides we Europeans, the locals in town then were mostly male. They worked as house staff or drivers, leaving their women back in their home village where they would be safe. They lived in small dwellings, sometimes no more than a shack, in the backyards of houses provided for the Europeans.

The first Papua New Guinean man I had any real contact with was Tom, who worked in the house for Ken; his job included cooking. There was not much chance of a relationship here: firstly, I knew not one word of Pidgin and, secondly, I expected to do the cooking! Imagine my horror when I picked up the lid from Tom’s pot of rice—and there were all the weevils

nestled on top! When they died during cooking, they floated to the top. ‘Just a bit of protein,’ Ken said.

Tom did not continue in our service when we moved into Kam Hong’s flat. Not only could we not communicate, but he strongly resented my taking over his job.

In the flat, my nemesis was the cockroaches. I marched into BP’s to ask: ‘What does one do?’ They sold me some poison that you could paint on the walls. I duly took out our paltry supply of dishes and foodstuffs and painted the inside walls of every cupboard with poison. I had solved the problem I told Ken.

After dinner I went into the kitchen to do the dishes—there were cockroaches everywhere. They were on the floor, on the bench, crawling up the walls and on the ceiling. Their cupboards were unfriendly, so … I was aghast. I grabbed a broom and began a frantic attack—smashed cockroaches were flying.

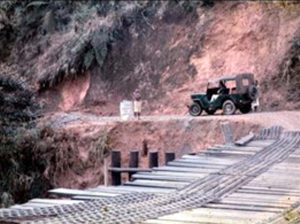

Our jeep, having just crossed a precarious bridge on the new Highlands Highway. Photo taken during a trip in

1963. Related in my book soon to be completed, My New Guinea World (

I have never forgotten my horror that night. And never, in 24 years in PNG, did I ever learn to accept them.

I still remember with equal horror a night we spent in the Markham Valley, about 30 miles northwest of Lae. We stayed with a friend, Tommy Leahy, who had a farm in the valley. Tom was a bachelor. That night when I got up at midnight to go to the loo, I had to cross the kitchen floor. As I stepped out, barefooted, there was a rustle and a whirr, and the floor became alive with cockroaches—hundreds. I went back to the bedroom and put on my thongs.

Around the tiny shopping area and administration buildings that formed the centre of Lae were government-built houses for families and dongas for single folks. Below the town was the beachfront with the Hotel Cecil, the airstrip and the wharf. These were our main connections with the outer civilised world. The beachfront, with a delicious sea breeze, was also the coolest place to be and one of our favourite places for an evening drive when we finally got a vehicle.

The beach was also where the rural villages connected with Lae, like the people in the photo who had sailed in on their lakatoi. This form of transport was no longer common around Lae. By 1962, motorised boats were taking over because they could carry more. Beyond the beach stretched the waters of the Huon Gulf—tainted brown with the discharge from the huge Markham River, just 10 miles west of the wharf. I still remember an evening drive along the waterfront when we watched for an hour as a local man worked to hollow out a log and started to put together a lakatoi right there on the beach one early evening in 1962.

Everywhere along the north coast of PNG was the wreckage left behind from World War II. Many of the rusting hulks became romantic icons, like the Tenya Maru, which came to symbolise the Lae foreshore for me. Many years later, when I took up scuba diving, these World War II wrecks were our favourite places to dive because they attracted so many fish.

The Tenya Maru, grounded on the muddy beach at Lae, was once a Japanese hospital ship during the war. After the winter storms of 1963, she slid deeper into the water until only a small part of the bow remained to show where the hulk lay. I always thought of her like she is in the photo: a dramatic wreck rising just behind the surf.

Our biggest splurge after we got married was the purchase of a Mitsubishi Jeep. It was exactly like the US Army jeeps only made in Japan (what irony). Of course, Ken had to test our new purchase, so we drove out the network of tracks called logging roads which criss-crossed the forest to the north of town. The area was drained by several rivers: the Butibum, Busu and Bupu are three names I remember.

‘Bu’ in the local language meant ‘milk’, and all these rivers were very muddy (milky?) in the rainy season. But January on the north coast was dry, and many rivers were visibly low, when our new jeep arrived. When we got to the Bupu River, it was no longer flowing, although there were a few pools.

Our first big adventure in the jeep was driving down the nearly dry bed of the Bupu. We headed off downriver, bouncing along over the stones and small boulders. It seemed as if we had left the civilised world completely, winding through the real jungle. I was in heaven. This was a true adventure and, in my mind, I expected every weekend with Ken from then on to be an adventure! To my dismay, once Ken was assured that the jeep could really perform in 4-wheel drive, we never explored another riverbed.