Surviving the Tari Gap, Papua New Guinea

Part One of the story of one pilot’s miraculous escape from a crash in an infamous jungle

Richard Broomhead

Between 1965 and 1996, there were 685 accidents (as opposed to incidents) involving aircraft in Papua New Guinea, that led to 467 fatalities. Most of these accidents were the result of controlled flight into terrain in single-engine aircraft.

Hundreds of aircraft lost during World War II are still unaccounted for. One problem was inaccurate maps. Still, there are currently no World Aeronautical Charts available for PNG either from Civil Aviation Safety Australia or the PNG equivalent. Local operators produce their own.

The New Guinea bush does not give up its dead easily. Tall trees, growing to well over 100 feet high, form a canopy, under which grows a second layer of trees, reaching to perhaps 60 feet. Below that, rotting tree trunks and vegetation produce a deep pile. Once an aircraft falls into this tangle it becomes almost impossible to spot from the air. Search parties on the ground usually rely on the smell of aviation fuel to find the wreckage.

Over the same period, 101 deaths involving 28 aircraft were the result of trying to fly through the high-altitude gaps or passes in the ranges, which rise to nearly 15,000 feet. Although the average sector length in PNG flying is less than 30 minutes, it frequently involves negotiating one or more of these gaps. The pilot flies through them on the way out to destinations and through them again on the way back to base.

In the Southern Highlands, the Tari Gap, between Mendi and Tari (a distance of 60 miles) accounted for seven of those crashed aircraft. At over 9,200 feet, and between mountains of nearly 12,000 feet, it was a difficult gap to negotiate in a normally-aspirated aircraft with a full load.

In the wet season it was a ghastly, haunted place in the afternoon. Often, the pilot had to climb up one side of the gap in swirling mist and rain with only 100 feet between the cloud base and the trees and then dive down into the valley on the other side in the same conditions.

The advice given to new pilots on flying gaps usually mentioned approaching at a 45-degree angle, ensuring that the valley on the other side is in full view, clearing the gap with a few hundred feet to spare to counter any downdrafts, etc. The fact is that if these rules were followed in the wet then no flying would have been done. There were few good roads through the Highlands until well into the 1980s. The outstations relied on air transport for all supplies. Everything had to be flown in, including fuel, boxes of nails, roofing iron, food, clothing and the mail.

Consequently, there was always subtle pressure on the pilots to ‘get the mail through’. One of the hardest things to drill into new pilots was that there was no stigma attached to aborting a flight and coming back to base with the load. Flying was generally called off for the day after the second abort.

In 1966 I was the first pilot to be based in Mendi, in the Southern Highlands, with a C185 belonging to Territory Airlines Ltd. On a number of occasions I scared the living daylights out of myself in the Tari gap. Now-retired pilot John Absolon is the only pilot to survive a crash there. I was on leave of absence from Qantas at the time and was involved in the search.

John joined Talair in September of 1975 and was posted straight to Mendi. By the time of the accident, 8 January 1976, he had been thoroughly checked out with the usual five checks over the route and three strip checks, fortunately before the onset of the wet, which could make the same route appear completely different. At the time of his accident, John had about 200 hours ex-Mendi, with a total of 1800 hours.

John recalls: That day was typical of the wet season, with the murk closing in around midday. The five Mendi-based pilots were sitting around the mess waiting for flying to be called off for the day, when the Port Manager came in with a request for an urgent flight to Koroba with two drums of diesel to supply the station generator. No one wanted to go west of the Tari Gap at that time of day but being the new boy and eager to please, I put my hand up.

On doing the pre-flight, I drained five small fire buckets full of water from the wing tanks. Obviously the seals were faulty.

I took off and then quickly offloaded the drums at Koroba (ten minutes flying time from the gap) and returned via the same route. I had to climb up to the Tari Gap from the west under almost full power, as the cloud base was just about in the trees and it had started to rain. When I got to the gap itself there was just a black wall of rain and mist on the other side. I pulled the aircraft into a steepturn to the right to attempt to go around via the south of Mount Kerewa.

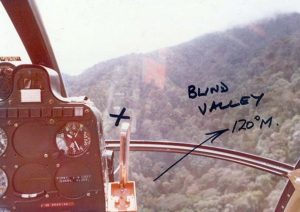

Just then the engine faltered and I lost about 50 percent of my power, probably the result of water in the fuel. I instinctively rolled the wings level and in doing so the engine ran smoothly again but I finished up off the usual escape route to the south-west. I was dodging in and out of rain squalls and mist with the cloud almost in the treetops. Descending rapidly down the slopes of Mount Ne I found my forward way blocked and I turned left, entering what I thought was an escape route but what turned out to be a blind valley.

Suddenly, a large treetop loomed out of the murk and I had nowhere to go. I threw the aircraft into a steep turn to the right but the right wing caught the top of the tree.

All I remember from the prang is the aircraft going round and round like a spinning top, huge g- forces and foliage flying everywhere; incredible noise. Then no movement, only silence.

This article was first published by Qantas Airways in its inflight magazine in 2009. It has been reproduced with the permission of the author, then-Captain Richard Broomhead, and the photos are courtesy of his brother, Ken Broomhead. Part Two will be published in the next issue of PNG Kundu.