Sel Kambang and Andapen

Part TWO • BAKA BINA

This story picks up from Part One in the March issue where Baka wrote about when he was in Grade 4 and the school children were being taught a song about Papua New Guinea’s new flag. He also described how the concepts of self government and PNG’s pending independence became lost in translation when discussed by people in his village.

The story continues:

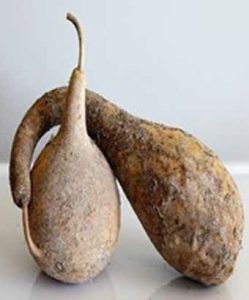

Dad was talking about the sel kambang from where we grew up. The Sununo pods we grew were calabash gourds used mainly as water or seed containers. Someone in my dad’s group said they were required to wear this sel kambang gourd around their lower parts.

He forgot to inform them that in some places smaller sized pods of the sununo gourds were used as lime pot containers, but in the Sepik and in Telefomin, the slimmer long fruits were used as penis gourds. Perhaps that was what Somare intended for them.

He didn’t need to describe penis gourds and sel kambangs. Our people had seen a group wearing them at the Goroka Show earlier. It was just that we did not have that variety of sununo plant in our place. They were to substitute the Telefomin gourds with their own round calabash sununo, and that is where everyone’s imaginations ran wild considering how to wear one let alone walk around with one attached to their legs.

‘Eh, the police are going to stop everyone and check if they are wearing sel kambang as we go into town.’ Chuckles were heard around the fireplace.

Who the heck was going to travel into town anyhow? We had to wait nearly all morning to jump onto one of the very few Public Moving Vehicles (PMVs) that trundled past our village and down the road to Asaro Station where we could pick up a 50-toea fare. It cost 20 toea to go into town from our stop, and by the time PMVs had room for us, the Traffic Police would have set up their regular weekend roadblocks, making it hard for those jittery old PMVs to make it into town.

Who the heck was going to travel into town anyhow? We had to wait nearly all morning to jump onto one of the very few Public Moving Vehicles (PMVs) that trundled past our village and down the road to Asaro Station where we could pick up a 50-toea fare. It cost 20 toea to go into town from our stop, and by the time PMVs had room for us, the Traffic Police would have set up their regular weekend roadblocks, making it hard for those jittery old PMVs to make it into town.

‘It is not that we won’t be wearing any sel kambangs; it is the indignation of being humiliated by little boys—these policemen who, because they wear a uniform, are going to ask us to remove our trousers or to lift up our skirts. Think about it! How they will treat and ridicule us elderly people.’

‘Gosh, they ask us to put on a calabash sununo so we walk around like ducks! What indignation is this Somare gavman trying to put us through? How do I hide this duck walk into town?’

‘Eh, don’t worry. Everyone will be walking with legs akimbo so no one will bother laughing about every other person walking like them.’

‘Heh heh heh.’ Soon everyone was rolling silly with laughter.

‘We’ll tell the children tomorrow—when they go to school they can tell those teachers, Masta Opokins and Masta Milati, that if we are to be forced to wear sel kambangs we expect them to show us how.’

‘I want to see Masta Opokins wear the Telefomin sel kambang and see his white balls pop out from the end of his sel kambang andapens.’

‘Hey, you kids, get to bed now. If you hear the grownups starting to swear, you may never grow up.’

As we children stood to leave, Maunten Mahn, the strongest man in the village, who could use his thumb as a screwdriver to undo rusted nuts, pressed his thumb onto the thigh of a woman sitting near him.

The woman whimpered with pain and shouted, ‘You think you’re being funny! But I am not wearing any Somare andapens that you might hope to see!’ And with that and a few hot-eared expletives, hobbled out of his reach.

When Maunten Mahn touched us, and I mean everyone, young and old, we always came away with whelping bruises and plenty of tears. Not only that but the indignation of being laughed at by everyone around us. Nobody wanted to be his victim. The crowd dispersed, returning to their houses with the thought of sel kambangs and andapens ringing in the night, only to be serenaded in the morning by the flag song.

When I went to bed, sel kambangs and andapens floated around in my head. I could not sleep so I lulled myself to sleep by humming the flag song in my head for a long while. •

Author’s Note:

Kambang is the Tok Pisin term for lime powder made from dried and crushed shells or coral that betel nut chewers dip into with a ‘mustard stick’. People grow betel nut palms and the pepper plant that produces the mustard stick, but kambang is harvested by people who live near the sea and reefs. They may do the processing themselves or sell it to middlemen who process it, selling the finished product, a white powder not unlike cornflour. The receptacle for holding the powder was the hewn-out pod of the sununo plant; Lagenaria bottle gourds. Over time and as they were traded inland, these receptacles then became known as sel kambang. How the penis gourds acquired the pun name as sel kambang is anybody’s guess.

Pitpit is a generic name for all canes, and most plants having marked stems where the leaves fall off are called by the generic name pitpit. There are various types, some strong, some soft with hollow inner parts like bamboo, some in between, including two edible ones where one is also known as New Guinea Asparagus. The one mentioned in this story is the strong variety that most Highland houses would have used in constructing beds.

Part ONE of this story can be found HERE