Omie: The Other Oro Tapa

Joan Winter, International Partner Omie Tapa Art PNG

The moment I stepped off the plane at Jacksons Airport in 1972 I fell in love with Papua New Guinea. I collected my first Oro tapa in 1979 from a haus win on the shores of a Maisin village. Fate would play its hand as I still have that first tapa. I will be buried with it.

When expatriates and nationals alike think of Oro tapa (painted beaten bark cloth), they think of the coastal Maisin of Collingwood Bay, its black, brown and white tapa that has been around since the 1930s and often used in national PNG design elements. This limited palette in a curvilinear style based on facial tattoos and clan designs is easily recognisable. Omie tapa is very different. It speaks to the incredible artistic wealth of hundreds of visual arts and cultural traditions practised in PNG today.

In 2017, I was visiting my goddaughter, Rahab, who lived in a village near Sirope on the track leading into Omie territory. I thought I was nearing retirement. No such luck. That’s when I happened to meet Omie people for the first time and after hearing their concerns with how their tapa was sold internationally, I was drawn in.

The Omie are a very remote group numbering about 2,000 people. They live on the southern slopes of Mt Lamington, Humaevo, their sacred mountain, in the vast tropical rainforest mountains of Oro, not so far from Kokoda. Within this small community today, there are well over 110 individuals, mostly women, practising tapa nioge making. They see their nioge as the only way out of extreme isolation and poverty, with sales enabling them to pay school and hospital fees, transport to Popondetta, etc.

The development and exposure of Omie nioge tapa is remarkable. In 2019 when I spoke to members of the annual Tapa and Tattooing Festival committee, they had never heard of the Omie. The Omie are surrounded by the Orokaiva, a much larger group who, at times, can be hostile, making it difficult for Omie to walk through their territory. The Omie were isolated but things were changing.

In the 1960s Omie patriarchal and patrilineal elders deliberated on the causes of two major events that rocked their world. The first traumatic event was the impact of WWII. Many Omie men were recruited as carriers. The second traumatic event was the 1951 eruption of Mt Lamington, Humaevo.

The Omie took this as a sign that their ancestors were unhappy. What should they do? The men had held their people’s cultural visual language by inscribing, etching bamboo pipes and tattooing young men for male initiation. Now, they thought the ancestors might be appeased by a highly unusual and dramatic transfer of major cultural knowledge to women. They would transfer their cultural knowledge onto nioge/tapa, thus making women the main interpreters of Omie visual culture today.

When David Baker, a prolific collector, came across Omie tapa around 2002, he was astounded. In 2006 Baker organised the first Omie tapa exhibition at Annandale Galleries in Sydney. It was a hit. The Omie decided to go straight to the international, indigenous, fine arts market, bypassing their own country. This, however, exposed the Omie to challenges and exploitation they could not understand.

On our first meeting, when I was invited to their nearest villages, Asafa and Godibehi, I offered to help.

At that stage only women created nioge, but as I created more opportunities to exhibit, women welcomed a few men into their nioge cohort. These men are usually the sons, husbands and family members of the significant original female cohort who exhibited in 2006.

In 2019 I curated their first exhibition in Brisbane. In 2021, their first and only travelling exhibition, titled Sihot’e Nioge—When Skirts Become Artworks, opened at Lismore Regional Gallery NSW before it toured to seven mainly regional galleries in Queensland. The last venue proposed is the Gab Titui Cultural Centre on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait—closer to home.

Omie tapa is remarkable for many reasons. At the beginning of time, the first man who arrived on earth asked the first woman to make tapa so they could become man and wife—a sacred act, making them the progenitors of Omie society. The first tapa was soaked in mud.

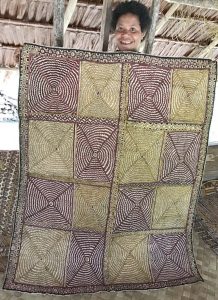

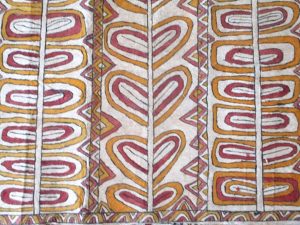

Two styles developed: grey mud-soaked appliquéd tapa, the other painted on the base cloth. The breadth of their iconography and imagery is vast; their compositional design elements are equally diverse, surpassing all traditional tapa from across the Pacific. Their infinite colour range made from natural plant materials is bountiful. Plants in all their glory, while being the substance of coloured paints, reveal themselves as edible plants, fruit, bark designs, tree branches, flowers and more. Omie imagery is infinite. Omie tapa artists look at the minutiae of the natural world as far as the stars and moon.

Centipedes and caterpillars form lines; grub, spider and dwarf cassowary eggs are represented by black dots; bird feathers open; fish gills and human ears, dragonflies and spider webs, pig tusks, bird beaks and jaw bones all multiply on the surfaces of beaten bark. Much of it is sacred. Bamboo is represented in cross sections and cut pieces. It was there on the first day the Omie arrived on earth as part of the original coupling. Unfurling ferns are often represented as the bellybutton tattoos boys were given to become men.

The mountains they live in are ever-present; the grid patterns represent pathways both literal and esoteric, with repetition providing a contemporary feel. Lizard and eel backbones form grid patterns, while mountains, represented by black triangles, form border designs. Totem imagery is common. Descendants utilise them in various ways, creating a staggering wealth of artistic talents.

There are protocols for making and keeping nioge/tapa safe, but how these have entered the wider world beyond their comprehension is a continuing concern for them. Unfortunately, as I must retire, the Omie tapa makers are looking for a replacement. Can you help in any way?

I am retiring, and prices for the tapa have been lowered this year. You can enjoy Omie tapa by visiting their nioge at Baboa Gallery at The Gap in Brisbane by appointment only. Please contact me on 0401 309 694 or email: joangwinter@gmail.com.