My Expatriate life – part two – Daru

The company sent pilots around to different places at whim, probably because most were single and that was the kind of job it was anyway. We had been in Lae for only short time and then we were transferred to Daru. Daru is a very small island off the coast of Papua, north of Thursday Island, very flat and dry, only two kilometres wide at its widest point where there was a sealed runway. Most of the islands in the Torres Strait belong to Australia but Daru is part of Papua New Guinea. The airport there was nothing much more than a hangar and we lived in it! That was the company accommodation. Inside the hangar, at the back was an office and above the office, upstairs, we lived in a small very basic two bedroomed flat. I became the ‘agent’, wrote tickets, organised the manifests and ‘cargo boys’ who loaded and off loaded the aeroplanes, and kept communication via the two way radio. One of the first things I had to do was to learn to drive and get a driver’s licence. There was a small company truck and Eric taught me to drive it. It had a gear shift on the side of the steering wheel and I wasn’t at all confident but after a while we went to the Daru police station and I got my PNG licence. I walked out with it, no test required, and drove back home to the hangar, bunny hopping all the way with our little daughter sitting between us saying, ‘Mummy, bumpy car!’

My husband flew the charters and the regular public transport flights which kept up the supplies to outposts in Western Papua. There were plenty of mosquitos, cockroaches and crocodiles. Luckily the crocodiles didn’t venture inland but there was a crocodile farm. Our little girl, now nearly three, called everything ‘crocaatches’. To her it seemed to cover every living thing, apart from people. I was there during the day by myself with the local people, the ‘cargo boys’ who worked with me. Eric would be away most of the day but other small aeroplanes would come and go.

The older ‘cargo boy’, Anakai, was much older than me at that time. He was a village elder, very respected by his people, highly capable, and a good worker. My pidgin improved a lot, thanks to him, as he would speak more slowly when talking to me. We noticed he’d developed a limp. Eric asked him about it but he just said, ‘Me no savvy,’ (meaning he didn’t know why he was limping). Eric took him aside and drove him to the hospital. The Filipino doctor said he had venereal disease and would have to take medication. We rightly assumed his wife would also be taking the medication and wondered how this would be explained to her? No, it wasn’t a problem, explained the doctor. As a respected elder and a wage earner, it was accepted that he had the rights to all women in his village. It was the way it was, a part of their culture. There was no problem other than the disease itself.

Living in the flat in the hangar, we were of course, the first port of call for any aeroplanes coming up from Australia and Thursday Island. One day a beautiful Citation jet landed from Australia with a group of wealthy travellers headed for a week of barramundi fishing at Bensback Lodge near Weam. The pilot and his passengers asked to be cleared by customs so I rang the number for them, explaining that an aeroplane had just landed from Australia and needed to be cleared.

‘No sorry’ was the answer.

‘What do you mean, No, sorry?’ I asked.

‘Customs officers not here. In jail’ I was told.

‘Customs men in jail? Why?’ I asked.

‘They are needed here, at the airport. Now.’

‘Sorry. Not here. They got drunk. Now in jail. You have to call the jail’ was the reply.

I called the jail.

‘There’s an aircraft here from Australia,’ I explained, ‘You have to let the customs men out of jail so they can clear the aircraft and passengers here at the airport.’ There was a blunt refusal, ‘No, sorry, they are drunk. They stay in jail.’ The pilot spoke on the phone but it was no use.

‘You come to the jail to see the customs officers,’ he was told.

The pilot and his passengers were wide eyed and incredulous! So was I.

So there I was, driving the company truck with Citation pilot and his wealthy passengers loaded in the back, bumping along the rough Daru roads, to be cleared by the drunk customs officers at the Daru jail! Sounds like a story but it’s true.

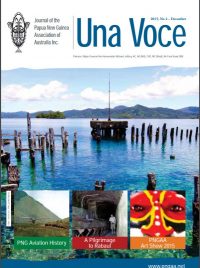

Daru was not especially beautiful in a tropical way. The landscape was a lot like much of outback Australia. It was dead flat with a few scratchy trees and bushes but it was very hot and humid with a dry and wet season. There was a constant smell of fish being smoked and dried by the locals. The rest of the world felt far away. It was completely quiet, except when aeroplanes came and went. The population consisted of about 3,000 local people and around 20 expatriates. There was an open air movie theatre and a pub, a club, two trade stores, a small hospital, government offices and two schools. There was also a Catholic Mission based there with French speaking Canadian missionaries. Sometimes they would fly out to visit different outposts. They made a name for themselves as when the supply boat arrived in Daru once a month they were often the first ones down there buying out all the chocolate on board! The publican and his wife were real characters. But that’s another story. There was a fish factory across the road from us run by an older expatriate Australian couple. They worked really hard, seven days a week while the wife constantly drank Avocaar liquor, adding milk, ‘To steady my stomach,’ she’d say. We lived on barramundi and crayfish and the only other food available on Daru were potatoes and sweet potatoes, although some of the locals grew their own vegetables. Apart from this we would get our supplies from Goroka, in the highlands, when the aeroplane went in for a service.

There was a crocodile farm on Daru, run by an Australian crocodile hunter who lived there with his wife and children. He bred them but he also kept two of these huge reptiles as pets, both about 14 feet long, kept behind chicken wire. We would go there to see them. Their eyes would look at just above the water in complete stillness, until Dave threw a chicken over the fence for them. The immediacy of strength and speed of a large leaping crocodile is a fearful spectacle! One day a government officer spoke to him, saying it was illegal to have such huge crocodiles in captivity. The government would have to take them but not just yet. That night Dave apparently released them. One headed for the sea and the other was found the next morning under the government building! The government officers were scared off going to work that day. It caused quite a bit of excitement on the island but the reptile was eventually caught. We were once invited to Dave’s for a tasting of barbecued crocodile tail. I wasn’t too keen at first but it tasted a lot like chicken.

The most beautiful part about Daru was the huge sky against the flat Daru horizon. It seemed to diminish the land on which we stood and even more so when the sunsets took precedence over everything, when the temperature would drop a little. This is when the flights would finish for the day and I would sometimes take my daughter for a walk in her pusher along the length of the runway. The sky would become a massive brilliant glowing of reds and oranges to start with, then dissipating to almost every other colour until the sun went down. There was a real presence and it was all so quiet. Then the mosquitos would come. We took our antimalarial tablets religiously.

One aspect I didn’t like in PNG was the attitude of many expats towards the local people. There was a fairly strong element of derision and racism by some, especially in the bigger towns like Port Moresby and Lae where there was also lots of petty crime. We were living in

their country and had so much by comparison; money, cars, clothes and possessions. Being a ‘wantok’ (extended family) sharing culture, my thinking was that they would see it as unfair. So when Eric arrived back in Daru one day with two very ‘bushy’ passengers in loin clothes, and rudely told them in pidgin to sit on the hangar floor and not move, I objected. They were skinny and small and fearful looking.

‘The way you just spoke to those passengers was so rude,’ I said. ‘Don’t worry,’ he replied, ‘They’re cannibals. They had an eating near Nomad River. I’ll phone the police to come and get them. Never been in an aeroplane before and never seen a building as big as this hangar! They’re pretty scared.’

I looked at them. They didn’t match the mental image I had of cannibals. I felt sorry for these cannibals.

While in Daru we improved the efficiency and organisation of the Daru base. My house girl, Daisy, was lovely. She cared for Robyn, our daughter, while I was working. During the day other flights would arrive and depart, mostly aeroplanes and pilots working for the same company. I would organise their offloading, reloading and manifests via the cargo boys. These pilots were an interesting, if not eccentric lot. One I particularly remember. He was about 6’4” tall with dark eyes, very long black hair and beard and spoke with a loud, expressive voice. He had to fit into a small Beech Baron aeroplane (a six-seater) so he did calisthenics in front of the aeroplane each time before he could fit into it. I think his passengers thought he was quite mad. He was very passionate and dramatic, always talking about his philosophy of life, using his massive hands to emphasise a point and quoting his favourite book, ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance’. There was also another pilot who wore a crash helmet when he flew. Apparently, he was an ex-military helicopter pilot. He wore it, he told me, in case he crashed. He developed a real affinity and respect with the local people. He learnt to speak Motu, a dialect in the Moresby region and chewed ‘betel nut’ as the locals did. The sad thing is that much later he did crash, due to a missed approach to an airstrip in a very narrow area, and he was killed. The locals for whom he had so much respect, were devastated we were told. There was also ‘Dangerous Dave’ who would sometimes fly into Daru. He was really well mannered but hyped up most of the time and he too, spoke in an overly dramatic way. I was never quite sure of what he was on about. He’d walk to his aeroplane with long, fast steps. ‘Get in,’ he’d say to his passengers. ‘I’m feeling dangerous.’

Then there was Robo. Like all the others, flying was all that mattered. He’d always be joking and he’d literally bounce out of his aeroplane with a smile, always ready with a humorous quip. One day I said to him, ‘Robo, if you couldn’t fly, what would you do?’ He looked at me with a smile, ‘Lay back on a roast spud and tread jelly!’ he laughed. Tread jelly?? Yes, they were an interesting lot.

The two-way radio I used most days was essential to the operation and organisation over remote parts of PNG. It also provided continuous and endless information and gossip. Everyone heard everything when anyone spoke and the humorous quips and comments were all part of the radio waves culture. Most voices were male, those of agents and pilots using minimal words in very Australian accents. So, I was all ears one day when I heard a very much older woman’s pucka British accent, ‘Port Moresby, Port Moresby. This is Wanigela…Over…’ ‘Yeah Wanigela. Gow ahead,’ was the Aussie reply. ‘Would you please make sure our crream cakes are on board today? We are expecting some American tourrists. Please will you check that they are on the aeroplane. You know how the Americans love their cream cakes…Over…’ There was a silence. Then the Aussie reply again, No worries. . . . Yeah.’ Silence again. Another Aussie voice came on, ‘This is the ‘bay bay say’ news!!’ (ie BBC news). I don’t know who this lady was or what she thought of all this.

It was when we were living in Daru in 1975 that PNG gained its independence from Australia. It was a very proud day for the people and there were great celebrations all over the country. PNG had been a territory of Australia’s since 1902. There were celebrations on the island and it was a public holiday. I can’t remember any immediate noticeable changes but of course since then there have been many changes with its governance and decision making as an independent country. We worked very hard in Daru, Eric flying and me organising it all on the ground. I was paid 5 percent of the company earnings so there was great incentive. Others thought we were crazy to actually enjoy living in such a place but it was a challenge and we saw it as an amazing experience. Living in the hangar at the airport, we rarely got a day off. We both worked very hard and I was starting to feel Robyn needed more of my attention. After 18 months we were feeling we’d had enough. Eric asked for a transfer and the company sent us back to Lae.

Diane Bayne