Memories of the Ok Tedi Fly River Development Trust

Nigel Robin Ette

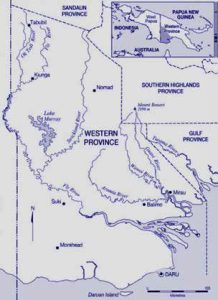

At the time of independence for Papua New Guinea, Western Province was undeveloped. It was the furthest province to the west, where high mountains take the Fly River to the sea via lowland plains. In January 1983, I was employed as a general foreman earthworks by the main construction company contracted by BHP, to begin the Ok Tedi project.

At the time of independence for Papua New Guinea, Western Province was undeveloped. It was the furthest province to the west, where high mountains take the Fly River to the sea via lowland plains. In January 1983, I was employed as a general foreman earthworks by the main construction company contracted by BHP, to begin the Ok Tedi project.

The contracted company was tasked with providing infrastructure for mining Mount Fubilan for Ok Tedi Mining Ltd. There was a gold cap atop Mt Fubilan, while the bulk of the mountain was high grade copper ore. A gold processing plant was established, followed by froth flotation copper processing on the ridge below Mt Fubilan, called Folomian. This was 20 km by road from the newly constructed town of Tabubil, adjacent to upper reaches of Ok Tedi (Ok meaning river or waterway).

The original plan was to capture the tailings from the mine process in a tailings dam situated on a smaller adjacent river, Ok Ma. In January 1984 (from memory), I was working night shift at the Ok Ma dam site, in charge of a quarry on the western bank of Ok Ma, that provided material for the proposed tailings dam.

That night the eastern side of the valley face of the proposed dam site slid into the newly begun construction area of the tailings dam, rendering unviable any ongoing pursuit of a dam. Early construction had unloaded the toe of the valley and the landslide, quiet, slow, steady, and relentlessly silent, nearly filled the void.

That night from midnight, the 400-man camp that was situated on the landslide had to be evacuated in torrential rain. The main construction camp one km away was not affected. I was still standing at the edge of the landslide in the early morning when senior management came along uttering appropriate oaths when they saw the whole tailings dam site had collapsed. There was also a heavy-duty corrugated iron bypass culvert structure built to take water from the Ok Ma while the dam was being built. This steel plate culvert five metres wide had been squashed flat. After due consideration management decided building a tailings dam was unviable.

Ultimately a dredge was employed near the village of Bige. Bige is on a side road between Tabubil and the Port of Kiunga, approximately in the lower third of the Ok Tedi, and north west of Kiunga at the junction of the Ok Mart, a tributary of Ok Tedi. It was a transition place where the raging torrent of Ok Tedi tumbled down from the mountains to emerge as a slow meandering stream, a tropical river on its way through flat lands to sea.

As a result of the non-construction of the tailings dam, funds were made available and transferred into Lower Ok Tedi and Fly River Development Trust, for the purpose of providing useful infrastructure for the villages downstream: i.e. haus wins (with galvanised roofs) to collect rain water, rain water tanks, school rooms, medical clinic rooms, community halls, and solar panels. This was the work now of the newly formed Ok Tedi Fly River Development Trust (FRDT).

I was appointed as the first project officer for this venture, which went all the way down to the sea at the Gulf of Papua; 104 villages with approximately 30,000 people. I kept the position for 10 years when I was replaced by a Papuan officer. The primary function of the Development Trust was to provide drinking water from the iron roof catchments.

The ensuing mine sedimentation changed the navigation possibilities of the mini-bulk carriers which transported copper concentrate from the river port at Kiunga to off-shore bulk carriers. At approximately 85 adopted river miles of the 420 nautical river miles from ocean to the Kiunga River port, mining sediment was deposited at that location because of the up to six metre spring tides. The sediment consisted of large granules all approximately the same size, like heavy sand. The tides coming in controlled the water flow going out, leaving the sediment from the mine on the riverbed.

The location of this deposit was named Muga Muga, which is more or less downstream from Sturt Island, and upstream from Wasua village; there is a  missionary-built airstrip at Wasua and a village called Lewada. The mini-bulk carriers bringing the copper concentrate downstream would anchor at this obstacle, often touching the bottom of the river bed while they waited for the high tide to cross. General cargo vessels drawing up to six-metres when loaded, were considerably inconvenienced when travelling upstream. This affected essential services of food supply to the town of Kiunga and the mining town of Tabubil.

missionary-built airstrip at Wasua and a village called Lewada. The mini-bulk carriers bringing the copper concentrate downstream would anchor at this obstacle, often touching the bottom of the river bed while they waited for the high tide to cross. General cargo vessels drawing up to six-metres when loaded, were considerably inconvenienced when travelling upstream. This affected essential services of food supply to the town of Kiunga and the mining town of Tabubil.

As a result, the provision of corrugated iron roofing and water tanks was a priority for the FRD Trust, of which I was the ongoing project manager. This entailed spending many days and nights down river, away from Kiunga and Tabubil and the life in the mining towns. On what is now the Indonesian side of the river, Dutch missionaries introduced Rusa deer which went forth and multiplied, providing useful meat protein for the river village people.

I lived on a ten-metre boat called the MV Alice, named after the wife of one of the original Fly River explorers, Lawrence Hargreaves, who appears on the Australian $20 note. The Alice was equipped with generator and freezer, so I too could purchase this meat to eat. In the evenings I fished on the tributaries of the river, catching Barramundi and Black Bass, which I often gave to the adjacent villagers and even to the Catholic nuns in Kiunga.

I tended to anchor overnight just away from the village and in a tributary for two reasons: firstly, to avoid catching malaria and secondly, to avoid being rammed in the dark by any of the 4,000-ton bulk carriers loaded with copper concentrate and travelling at 12 knots downstream at night. There were eight such mini bulkers. The safest off-river anchorage and good fishing was in the Agu River, mid-Fly. There were also other suitable side streams where I could safely anchor at night.

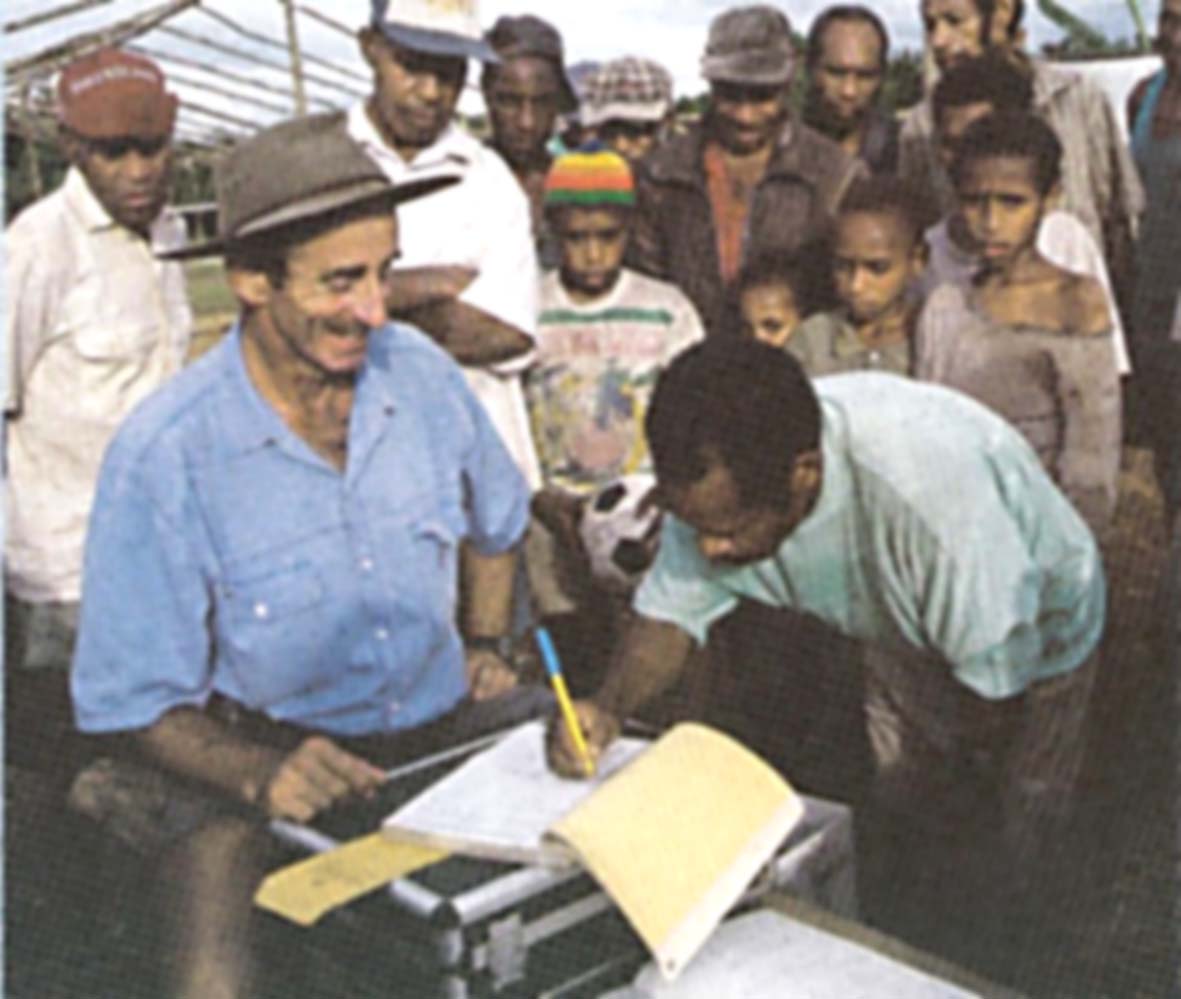

Along the Fly River, between Kiunga and the ocean, there are nine language groups. I liked the people as they were receptive and friendly. When deciding on village projects I always gathered the whole village together so that everyone heard the discussion. Primarily the villagers desired education for their young ones—to have future money earning opportunities.

I created a system of employing local area supervisors who had the appropriate language and knowledge to select the working groups. I employed women who were also included in the discussions. Women largely carried the work materials from the boat to the village site and it was the men who constructed the projects. I provided hand operated sewing machines and bolts of bright, coloured materials for the women to use, and they loved this. Many of the community halls built became largely women’s club meeting centres. It was important to speak to everybody to avoid potential internal village conflict.

Unfortunately, many of the American missionaries ‘planted’ a church and then went home, having delegated pastoral care duties to village leaders. The Evangelical Church of Papua (ECP) was much better, and different, because they provided hospitals and administration as did the Catholics, and they stayed long term in the field, often for many years. One of the missionaries’ very important jobs was to learn and preserve in writing many of the languages.

I was in PNG from January to October 1988 in the mining area, then the FRDT from 1990 to 2000, when I left PNG. Now at 73, I am unwell, living comfortably in the Central Queensland bush on 50 acres, and reminiscing. I look back on this meaningful work and hope it all flourishes again one day. The young people were intelligent and looking for jobs and programs and proper pay, for the future of their country. I believe the concepts started will be remembered and persist with the younger generation, despite the central problems in PNG at Port Moresby. I wish them all well.