Memories of PNG’s Independence Journey

Australia and Papua New Guinea share a deep historical and contemporary relationship, highlighted by the warm respect between peoples from both countries who have shared the journey to independence and beyond.

The PNGAA embraces initiatives to highlight and develop cultural understanding and education between the two countries, along with robust civil links. Over the last 50 years, there have been many stories featured in the PNGAA journals celebrating independence, some of which are republished here to showcase our connection and strengthen our future.

We also feature new stories, which will bring back many memories.

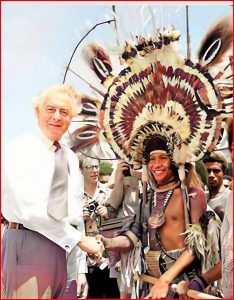

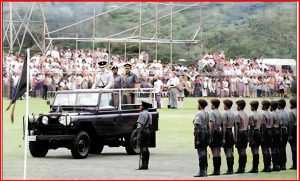

The Committee of the PNG Independence Celebration Organisation saying goodbye to the royal visitor at the end of his 5-day visit.

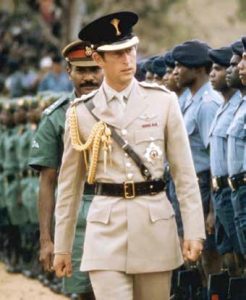

HRH Prince Charles, representing Queen Elizabeth II, at the Independence Day celebrations, Port Moresby (Ross Wilkinson).

A sing-sing at the primary school at Erap Agricultural Station in the Markham Valley on Independence Day, 1975 (Ann Mallard)

.The Road to Independence

A Papua New Guinean casting his vote at the New Guinea Elections in 1964 (Photo Frederick Carter, National Library of Australia).

The first general election in PNG was held between 15 March 1964 and 15 April 1964. This election, in which more than a million registered voters participated, was an important first step on the road to independence in 1975. The election was preceded by the passing of the necessary enabling legislation by the Australian Parliament and then many months of painstaking work by officers of the Department of Native Affairs (DNA—the kiaps) in establishing electoral rolls throughout the Territory of Papua New Guinea. All adults aged 18 and older were identified and included on the roll. The only people not included were those in Restricted areas which were determined to be too hazardous for entry.

In 1964, I was officer in charge of the Central Veterinary Laboratory at Kila Kila. We lived in Huala Place, Boroko. The latter is relevant to this story because Quentin Anthony, who was Assistant District Officer (ADO), Central District, and responsible for managing the voting for the Moresby Open and Central Special electorates, also lived in Huala Place. There were polling places distributed throughout these electorates which included people in the Tapini, Goilala and Koiari areas, as well as those in Port Moresby and the coastal villages of the Motu people.

There were not enough people in DNA to staff all the polling booths. Volunteers were needed and Quentin suggested to me that I might like to be the Returning Officer for one of his polling places. Initially I was reluctant, concerned that I might have to trek into some remote part of the Goilala, but when he told me that he wanted someone to man the booth on Gemo Island on a nominated Saturday I was happy to accept.

Gemo Island is in the northwestern corner of Port Moresby’s harbour and, after its purchase from the people of Hanuabada in 1937, had been an isolation hospital for people with either tuberculosis or Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Founded by Constance Fairhall of the London Missionary Society (LMS) the hospital was operated jointly by LMS and the Papuan administration. The army took control of Gemo during the Second World War, but it reverted to its original role in 1946. From then to 1960, Rachel Leighton was the senior LMS nurse at the hospital.

Postwar, European Medical Assistants and doctors helped in patient management at Gemo which now housed patients from throughout the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, and their numbers increased through the work of Department of Public Health specialists in tuberculosis and Hansen’s Disease, Stan Wigley and Doug Russell, respectively. When the hospital closed in 1974 Myra Macey was the last of the Gemo sisters. (See PNG Kundu, June 2021).

So it came to pass that, on a Saturday morning in March 1964, I took the government launch for a 30 minute ride to Gemo, armed with instructions for collection of the votes of the 389 people on a previously established roll. This number included staff and other people resident on the island as well as patients. In this first, universal suffrage election, voters had to choose their preferred candidate in two electorates – Open and Special. The day proceeded slowly, many voters obviously puzzled by what was, for them, a unique experience. Some Hansen Disease patients needed help to get their names or marks onto the ballot paper.

My role as a volunteer Returning Officer ended when I delivered the Gemo Island ballot box to Quentin later that Saturday. My voters were responsible, in a small way, for electing Eriko Rarupu, a Tapini man, as member for Moresby Open and Percy Chatterton of LMS as member for Central Special. And I had the privilege of helping those voters take a small step on the road to the independence of Papua and New Guinea.

JOHN EGERTON AM

Harry West’s Journey

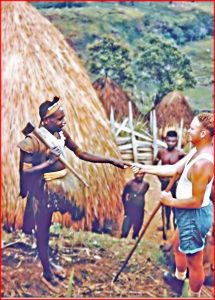

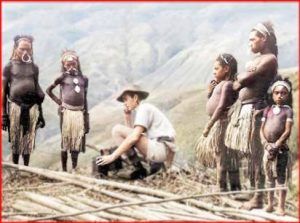

The famous photo of Harry West, as a patrol officer, wearing his trademark sleeveless singlet, meeting with residents in the outlying regions in the leadup to independence

Loved and highly respected, long-time president of the Papua New Guinea Association of Australia, Harry West OAM, died in 2015, but he had steered the PNGAA for 26 years until stepping back in 2008 from his role as President, which he had held for 16 years, when he was unanimously voted an honorary life member of the PNGAA and in 2009 he was awarded a Medal (OAM) of the Order of Australia in the General Division ‘For Service to the Papua New Guinea Association of Australia’.

As a kiap, Harry had a meritorious career and was held in high regard by both fellow kiaps and all those who knew him as a friend, or through business, during his 30 years in PNG, and after he returned to Australia.

It was during his time as District Commissioner in Rabaul that the town attracted a number of political and state visitors—Gough Whitlam came in 1970 and Harry’s clash with him led to hours of debate in the House of Representatives with senior politicians either praising or denouncing Harry, along party lines.

Prime Minister Gorton visited Rabaul not long after Gough Whitlam. Next, PNG Administrator David Hay arrived to tour the Gazelle Peninsula. Soon there was a top-level conference in Moresby, and cabinet ministers came from Canberra.

Towards the end of his PNG career, he was promoted to First Assistant Secretary in the Department of the Chief Minister, before leaving PNG in 1973, but he remained closely connected through the many friends he made there.

However, a letter from the Chief Minister, Michael Somare, later Sir Michael, written in April 1974, epitomised Harry’s enormous contribution to Papua New Guinea:

Dear Harry

It is with sincere regret that I learn of your impending retirement because of ill health. I am very conscious of the outstanding role you have played in the progress of our country over the last 28 years, and I realise that a man of your wide experience and understanding would be invaluable to us as this country moves through the independence period.

Independence will bring us problems, but the public services and the people will be able to cope with those problems, due to you, and to others like you, who have given a lifetime of service with this object in view.

I would particularly like to acknowledge your personal role during the difficult times of the Gazelle Peninsula. I know that your knowledge, tact, and understanding helped in no small way to bring about a peaceful settlement to that extremely tense situation.

I thank you for your sound counsel, always so readily available, and always so necessary to the important decisions in the political field.

I wish and hope that you can be with me on Independence Day on 1975.

ANDREA WILLIAMS

Papua New Guinea’s Transition to Independence

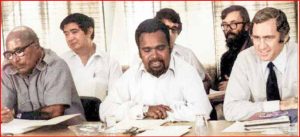

THE NEW GENERATION OF POLITICAL LEADERS IN 1972, PREPARING FOR SELF-GOVERNMENT (From left to right) Dr John Guise (Deputy Chief Minister), John Yocklunn (adviser to Pangu), Michael Somare (Chief Minister), Tony Voutas (Pangu strategist, partly obscured), Tos Barnett (adviser to Chief Minister) and Andrew Peacock (Australian Minister for Territories) (Photo courtesy Donald Denoon)

I made my first visit as Australia’s Minister for Territories in 1972, with my firm view that, given the stirrings and demonstrations, if the government sought to restrain the movement towards self-government and independence, it would bring about a backlash of perhaps even horrific proportions— even in a relatively small country such as PNG.

I made something like twenty-one trips to PNG in 1972. But, as I said, I was already convinced when I first arrived that we had to move sooner rather than later, although I was constrained in the first two months because we had to await the House of Assembly elections. This election was fought on the issue of whether or not there should be internal self-government. The elections were held in late February and early March and was won by the Pangu Party headed by Michael Somare.

So, PNG now had a government comprising a national coalition that, in the case of Pangu, wanted immediate self-government, but in the case of the People’s Progress Party was more interested in the form of the government that was put together. Michael Somare said, ‘I want early, not immediate, but early self-government, but at present I’m more interested in the shape of self-government.’ I responded by proposing that we hold constitutional talks in June 1972. Interestingly enough he suggested a month later.

I want to emphasise that all of the travelling I did to PNG and all of the discussions I held there just reinforced the view that though Australia had been slow at moving towards acceptance of independence, we were now on the right track. The worry was always that when we did transfer power, there would be a lack of depth in the PNG civil service. It seemed to me we couldn’t correct that overnight. We had established training colleges and these were doing a sound job, but there were still insufficient trained people.

On 27 and 28 July, Michael Somare and I sat down to discuss the transfer of extensive legislative and administrative power to PNG. We had an enormous range of powers and programs to hand over. Some powers had already been transferred but even so Australia had until recently exercised a veto because the Governor General, on the advice of the Minister for External Territories, could overturn any proposal by any minister in PNG.

This period really did see the development of a framework for PNG as a fine independent nation, and I think it is important to recognise that the way in which a trustee leaves a territory is extremely important. I was always very proud of the way we finished the job.

I should add that there were also, of course, pressures in Australia, from those in favour of a federal structure, to desist from faster moves to early self-government. But I was strongly of the view then that a country, containing 500 different tribes speaking more than 700 different languages, needed not a fragmented system, but a more centralised system.

I’d always believed that Bougainville ought to have a degree of autonomy, but when the provincial system of government was first mooted in PNG, I discussed the matter with Michael Somare, who said: ‘If I don’t establish a provincial system, I may lose Bougainville and PNG will end up just another exporter of coffee, tea and copra. I have to have Bougainville’s copper contributing its resources and revenue to the task of nation building. Unless I give that autonomy, PNG will not be a viable entity.’

I think PNG owes the Somares and the Chans of this world an enormous amount. Particularly, at that time, Michael Somare. I had met Somare when I first went to PNG and when he was an angry young man. He was to become a very close personal friend. I suppose in those days we were both a couple of smooth operators and we probably deserved one another! But we were able to achieve a fair amount together and his astuteness, his timing, his capacity for negotiation in 1972 in putting that coalition together was something at which I marvelled.

PNG achieved independence on 16 September 1975 and here we are in December 1993. I think we are witnessing a situation where, for whatever reason, bilateral relations have drifted somewhat. I think it is a slightly ominous drift.

ANDREW PEACOCK

(Edited extract from Lines Across the Sea: Colonial Inheritance in the Post-Colonial Pacific, 1995)

They Didn’t Tear Down the Flag

It was radio which really took the news of independence to Papua New Guinea on 16 September 1975. A vast hook-up by the country’s National Broadcasting Commission, planned for three months, reported it to an estimated 1.5 million of Papua New Guinea’s 2.6 millions scattered throughout the country.

At one minute past midnight they heard the brief proclamation of independence by the Governor-General, Sir John Guise, preceded by speeches by Prime Minister Michael Somare and lesser leaders. And, for the next two days, they had detailed reports or direct broadcasts of the festivities in the national capital and the main towns. Most of PNG’s population does not live in the urban areas. Even those who do, who had a village to go to, had gone home—to be back in the womb, as it were, at a momentous time.

So, in fact, Papua New Guinea has had two kinds of independence celebrations: the quiet grass-roots independence of the vast majority, and the busy, efficiently—organised, smooth-running celebration in the national capital, dominated by VIPs from 37 nations and by white faces.

Both celebrations have been a success. After nearly a century under Australian influence of one degree or another, the Australian flag came down with due deference. It was replaced by the already familiar scarlet and black flag with the soaring yellow bird of paradise.

Sir John Guise receiving the Australian flag after its formal lowering from George Ibo (in charge of the flag party)

A church leader used pidgin to bless the national flag at the Port Moresby ceremony which set the seal on independence:

‘Mak bilong bung wantaim long mipela’ (The mark of unity of you and me) said Bishop Herman Topaivu of the Roman Catholic Church, one of two chaplains who bowed their heads to bless the brilliant bird of paradise flag.

Then the flag was raised above the tree-studded hill where PNG will one day build its national parliament. Independence Hill will be the official name of the area where the formal flag-raising ceremony was held.

The ceremony followed the formal lowering the previous day of the Australian flag after nearly a century of colonial administration in PNG.

A cloud of gas-filled balloons in the red, gold and black colours of the PNG flag rose beside the hill at the conclusion of the ceremony.

Huge crowds—far greater than anticipated—created congestion on the roads and foot tracks leading to the ceremony. The area is at Waigani, an outer Port Moresby suburb, site of PNG’s national civic centre which is still under construction in partly-cleared land.

During World War II, the area was dotted with fighter dispersal bays, and it was from one of these—near the new Supreme Court building—that the cloud of coloured balloons was released.

Some of the access roads were sealed only five days before in the rush to get the area ready for the independence celebrations, and during the ceremonies bulldozers and graders stood silently at some of the approaches.

Australia’s flag comes down for the last time in Port Moresby, at sunset on Independence Eve.

Stuart Inder

Extract from Pacific Islands Monthly, October 1975

Be Specific, Say South Pacific

Returning to PNG after an absence of five years, we arrived in Port Moresby on 12 September 1975. After depositing our baggage, we headed for the stores for some necessities. Here, we found, to our horror, that the most important item on the shopping list was unavailable, as an embargo on the sale of liquor prior to Independence Day was in place. The great occasion looked like being anything but a celebration. However, the day was saved by an old DCA hand who, bless him, had taken the motto ‘Be Specific, Say South Pacific’ to heart; had stocked up for a few rainy days, and helped us out so that we were able to greet the dawn of a new era in the manner to which we had grown accustomed.

John & Christina Downie

Lowering the Flag

It was a sad moment for many of us when our flag was lowered for the last time as the official one. The raising and lowering of it had been a daily ritual in our lives for many years. At sunrise and sunset, on every government station, right throughout the country, no matter how small, the police paraded first in front of the District Office and then marched to the residence of the officer in charge and raised or lowered the flags. If there was a bugler on the station, ‘Reveille’ was played at sunrise and the ‘Retreat’ at sunset and, in places where there was no bugler, a Kibi shell was blown to signal the ritual was in progress. Any person outside, at these times, stopped and faced the direction of the flagpole and stood at attention. Even in the primitive areas, the patrolling officers ‘showed the flag’ wherever they stopped during their patrols.

Nancy Johnston

From the Memoirs of the late William J Johnston

A Wonderful Time

Independence Day was a wonderful time of celebration after preparation following on from Self-Government. Young, educated, Papua New Guineans eager for the job of running their own country were aware that there would be many challenges, but they felt ready. Their desire was for the Konedobu workforce with both Australian and local staff to carry on with the daily administration. This routine work generally ended up with a qualified PNG national, ably assisted by a former office bearer.

A number of celebrations both before and after the big day were enjoyed by old and young, as well as those in between. These included three different church services, with the Papuan one held at Poreporena, Hanuabada Village, in the United Church, a Pidgin one held at the Lutheran Church, Koki, with the English one at the Catholic Cathedral, Ela Beach. All these attended by dignitaries and people from all walks of life.

On 15 September a special ceremony at the stadium was held to lower the Australian flag. Rather sad in a way but, as mentioned by the Governor-General Elect, it had been lowered and not torn down.

Night brought a storm with its own fireworks and typical heavy rain. After the storm had moved on there were local fireworks and, on midnight, the Governor-General Sir John Guise announced via National Broadcasting Commission (NBC) that the country was now Papua New Guinea and independent.

The big day dawned calm and the early sunshine saw all roads leading to Waigani. As the United Church Volunteer Business Manager, together with Margaret Peterson, a senior educationist, we hailed the first passing truck, already pretty well packed with local enthusiastic Papuans and made a joyous bumpy ride to about as far as transports were allowed. This was followed by a rather boggy walk until reaching newly-laid bitumen leading to where the morning’s event was to take place.

A very important part was the dedication of the Foundation Stone for the new Parliament House. Not the privilege of politicians but, as a Christian country, religious ministers did the honours. Bishop Ravu Henao of the United Church to pray in Motu and Bishop of the Catholic Church to pray in Tok Pisin.

Prince Charles, representing Queen Elizabeth II, was dressed in Dress Army Uniform and walked right past me having a rather animated conversation with the Commander of the Defence Force. Their backgrounds could not have been more different with one having an upbringing providing his needs, the other from a remote village in the Owen Stanley Ranges, early mission education before chosen for further study and training in Australia.

The afternoon and days to follow were spent winding up celebrations before the real work began.

Nita Tobin

Independence Day & Imelda

Papua New Guinea had two kinds of independence celebrations: the quiet grass-roots independence of the vast majority of the population, which was enhanced through a vast national hook-up by the National Broadcasting Commission, and the busy, efficiently-organised, smooth-running celebration in Port Moresby, dominated by the presence of VIPs from 37 nations.

In covering that week for the Pacific Islands Monthly, I was able to report both kinds of celebrations were resoundingly successful. But that’s not to say there weren’t unexpected, off-beat, or exasperating occasions—and in that latter department one of the official guests, Imelda Marcos, First Lady of the Philippines, contributed more than her share.

To start with, she insisted on flying in to Jacksons in her own stretch DC8 with a huge entourage, despite the fact she had been warned of Port Moresby’s doubts whether the runway could take the load. The greater part of that entourage comprised security men, who surrounded her in a flying wedge wherever she moved. Others of her entourage invaded the press room of the big international media contingent, piling our desks unasked with expensive glossy publications outrageously extolling the virtues of Imelda, who did so much for her people.

Meanwhile, she arrived late at the flag-raising ceremony and was unpardonably late for the State Opening of the National Parliament by Prince Charles, and thus interrupting proceedings and, later at Government House by attempting to take precedence at the formal presentation of diplomatic credentials to the Governor-General, so enraging one diplomat that he walked out.

But this was 1975, and I regret I probably missed a good story angle by failing to ask about the number of expensive pairs of shoes Imelda brought with her.

Stuart Inder

Flags & Freedoms

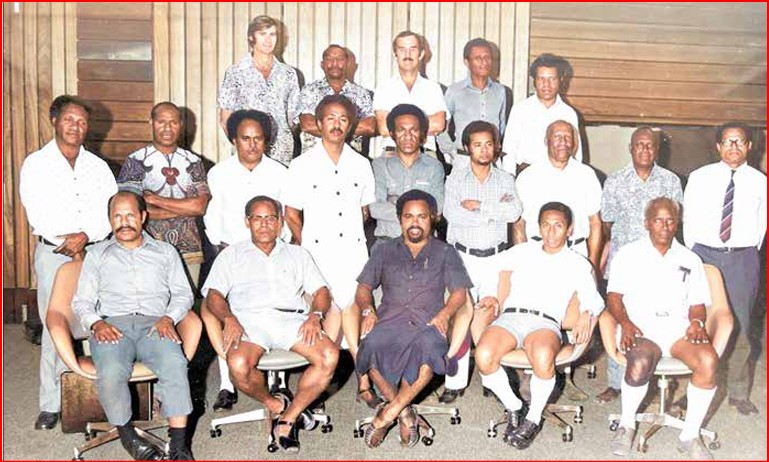

Members of the first PNG National Executive Council, 24 September 1975

(Secretary of the NEC, and the author, Mark Lynch, is first left in the back row)

It is the afternoon of Monday, 15 September 1975, the eve of PNG Independence.

In a ceremony watched by thousands around the grounds and in the grandstand at Port Moresby’s Hubert Murray Oval, Australia’s flag will be lowered for the last time as the flag of the Territories of Papua and New Guinea. Queen Elizabeth II is represented by her Australian Governor-General, Sir John Kerr. Also present, are dignitaries from countries around the world.

As I take my seat, I see Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam standing about 20 metres along the row, talking with Indonesian Foreign Minister, Adam Malik. What are they discussing? In less than two months Whitlam will no longer be Australia’s Prime Minister and, a month after that, Indonesia will invade East Timor.

The grassed oval below is busy. Groups of traditionally-dressed dancers are swaying and dancing to their singing and drumbeats. A large, green-uniformed, contingent of the Pacific Islands Regiment (PIR) contrasts with a smaller group of white-uniformed sailors and the white-uniformed band of the Royal Papua and New Guinea Constabulary. Looking around, it feels everyone is sharing a strong sense of excitement, drama and history.

The side gates open to a cavalcade of official cars that halt at the edge of the grass. The Official Party, including HRH Prince Charles in military uniform and his uncle, Lord Mountbatten, emerge and walk slowly past the dancers, towards the flagpole area in front of the grandstand. Lord Mountbatten hangs back for a minute to film a line of dancing women.

The Police Band plays as the dancing groups withdraw and the PIR soldiers, who today are part of the Australian Army and are about to become the PNG Defence Force, form into a long line across the oval, from one side to the other, facing the flagpole. A cooling breeze ensures the flag flies proudly, as if it knows it is the centre of attention.

Five unarmed soldiers march to positions beneath the flagpole. An order rings out. The soldiers raise their automatic rifles to their shoulders, pointing skywards. The crowds settle. To the order ‘Commence’, a military salute of staccato rifle fire crackles in sequence, a sharp ripple of noise moving rapidly along the line from one end to the other, a military feu de joie.

Attention now turns to the flagpole. A soldier steps forward and unties the rope. To a slow march from the Police Band, he gently lowers the still-waving flag. The flag seems determined to put on a cheerful show despite this being the end of its seventy years reign in this land. As it nears the ground, the other four soldiers step forward. Each take a corner, stretching the flag horizontally.

As the soldiers commence a slow march to the Official Party, the famous PIR bagpipe band bursts into life with an emotional, wailing rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

I’m surprised by an unexpected surge of nostalgia. My mind flips back to when, as a young patrol officer, the flag was a powerful and practical symbol of government presence on patrol posts and when visiting remote mountain and island villages. Tribal disputes negotiated and settled beneath this flag would be accepted as official and binding.

The soldiers skilfully fold the flag into a square package. Sir John Guise, who attended the Queen’s 1953 Coronation in London, and who at midnight will become PNG’s first Governor General, makes a short speech pointing out the flag is not being torn but lowered with respect.

A soldier presents the folded flag onto the arms of Sir John Guise, who turns to the Australian Governor General standing behind him. In silence he steps forward and presents the flag to Sir John Kerr. He steps back to attention and, in the manner of the former police sergeant-major he was in his early years, snaps a professional, final salute to the Governor-General and the flag of Australia.

It is a moving moment for everyone, be they Papua New Guinean or Australian.

The grandstand is silent. Looking around me, I’m surprised to see many of the PNG women spectators are tearful. Are those tears rolling down cheeks, tears of sadness at the passing of an era, perhaps tinged with a sense of uncertainty and anxiety about what lies ahead? To me, that’s what it looks and feels like. But I can’t know that for sure. Tomorrow, at newly-named Independence Hill, there will be a flag-raising ceremony for PNG’s own new bird-of-paradise flag. If there are tears tomorrow, I expect they will be tears of pride, hope and joy.

At midnight tonight, Papuans, the inhabitants of the Australian Territory of Papua, will no longer be Australian citizens. New Guineans living in the United Nations Trusteeship of New Guinea, will no longer be UN Protected Persons. Both populations will become citizens of Papua New Guinea.

Tonight, official dinners are being hosted by senior PNG parliamentarians, at hotels and restaurants across the city, to welcome international delegations who are here to welcome and celebrate the arrival of a new member of the family of nations.

The previous week, Chief Minister Michael Somare, known to those around him as ‘the Chief’, made a last-minute decision to hold a private dinner the same evening. I became aware of this when presented with an invitation for my wife and me to attend, at a government house on Touaguba Hill. Guests will have a good view over Fairfax Harbour where a fireworks display is planned for a minute after midnight, the moment after Sir John Guise, as Governor General, will broadcast the Declaration of Independence on radio.

Our family lives on the banks of Laloki River, some 25 km from the city. We had already promised to take our three young children (ages eight, six and two) to town to see the fireworks. That evening, we drive them into town with us before going to dinner. We leave them all with PNG friends in a suburb about a six-minute drive from Touaguba Hill. The plan is to collect them later and bring them up to the venue before midnight.

As the guests assemble, everyone seems to have been impressed by the afternoon ceremony—the packed grounds and stadium, the spectacle of brilliantly dressed dancing groups, the stirring poignant wails of the army bagpipe band, and the drama of the big flag fluttering down, topped by Sir John Guise’s last emotional salute.

Guests are looking forward to dinner, the fireworks, and being with Michael Somare, who is about to become PNG’s first Prime Minister.

Between 25 and 30 people are gathered for the evening. Looking around, it is hard to miss Gough Whitlam, and his wife, Margaret, although the Fijian Prime Minister, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, here with his wife, Ro Lady Lala Mara, is equally tall and impressive. They tower over the Somares and the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Chief Minister, Solomon Mamaloni.

Moving in from the garden, we take our seats for dinner. At the centre of the top table, the Somares are flanked by the Whitlams on one side, and the Fijians on the other. The only other politician I see in the room is Minister for Health, Dr Rueben Taureka, accompanied by his Fijian wife, Akanisi.

During dinner, word is passed round that Prince Charles will join us later for coffee, and stay on till midnight. After the main course, Somare stands to speak.

He welcomes everyone and says some may wonder about the variety of people gathered here tonight. He asserts that all of us are here because each in his or her own way has made a special contribution to bringing about the event that we will celebrate at midnight. He wants us to share the occasion together.

To Ratu Mara, Somare speaks of how he had watched with great interest, and had drawn inspiration from, how he had achieved Fijian Independence in 1970. He is honoured to have him and his wife present tonight.

Turning to Gough Whitlam directly, he especially wants to thank him. He recalls talking with him about Independence, about this night, one evening as they walked along Wewak beach in his home town. That was 1970, five years ago, when both of them were in Opposition.

Somare reminds Whitlam that since 1972, when they both formed their respective governments, they have worked together to achieve an enormous number of necessary legal, political, financial and administrative tasks in Canberra, Port Moresby, and the United Nations, to enable Independence to become a reality. This includes widespread consultation across PNG to prepare a home-grown Constitution.

Somare observes that while they had some difficulties and the occasional disagreement along the way, both were determined to reach the same goal. And so, it is truly an enormous honour to be able share this night together with Gough and Margaret Whitlam.

After warm applause, Whitlam stands to speak. He thanks Somare for his kind words. He praises the manner in which PNG undertook a highly consultative process in developing its Constitution. ‘In fact’, he says, ‘I am envious that you will have only one parliamentary chamber, and 5-year parliamentary terms.’

Whitlam emphasises Australia and PNG will always be close neighbours, sharing a common border and the waters of the Torres Strait. History and geography dictate there will always be a close relationship between us.

He asserts that, while tonight is undoubtedly a night of freedom for PNG, it is in some ways also a night of freedom for Australia. In his view, Australia cannot be truly free as a nation while it retains authority over lands and people not directly represented in the Australian Parliament.

‘Today the Australian Flag was lowered with dignity and affection, in a splendid yet moving ceremony. Now … tonight … it is such … a great honour …’

At this point, Whitlam’s words slow and falter, his voice changes, more hesitant, more choked. Everyone is looking at him, the room totally quiet. His words stop flowing but not the tears in his eyes. He seems quite overcome.

Gough recovers and regains composure. He tells the Chief what an extraordinary and wonderful honour it is to be with him tonight—to be able to share this historic occasion of the birth of a new nation of which he is about to become the first Prime Minister.

Afterwards, while chatting over coffee, I ask Margaret Whitlam, ‘Does your husband get worked up like that very often?’

‘No, not at all,’ she replies. ‘I was very surprised. I’ve never ever seen him like that before.’

Soon after, Prince Charles arrives. It strikes me as incongruous that he’s wearing riding boots with silver spurs on the back, as if he has just dismounted from a horse, but he seems at ease mingling with the guests. I notice Dr Taureka’s two teenage daughters have also joined us since dinner and seem fascinated to be in the company of a real prince.

Shortly after 11.00 pm it’s time to collect our children to be back by 12 midnight. Outside, we explain to the security police what we are doing and walk to our car parked nearby.

But the street outside has changed. I have failed to take into account how many people are flocking into the city. Cars are already parked all along the street and people are milling around looking for vantage points. As I drive down the hill and towards the nearby suburb, there is a continuous stream of headlights coming in the opposite direction.

At our friend’s house, the children are quickly on board and we soon join the slow traffic crawling into town. When we finally reach Touaguba Hill, the nearest space to park is hundreds of metres from the house and it is already five minutes to midnight! Hope is fading fast that we can get there in time. As usual, it’s a hot and humid night.

With my son piggy-backing, and the two girls holding hands, we set off uphill as briskly as we can. It’s soon obvious we will not make it. We are still more than 100 yards from the house when the first fireworks explode into the air. We slow down.

Lamari Valley 1963: Mark Lynch as a kiap at Wonenara Patrol Post, at the time one of the last 3 Restricted Areas in PNG. The Wonenara jurisdiction covered the southern side of the Lamari River. Villagers are watching and wondering what Mark is doing talking to something, as he makes a radio call back to the patrol post. (Theses photos have been digitally colourised.)

As we enter the house, the children are still hot and flustered from rushing up the hill. Inside, the mood is buoyant. Most people have a glass in hand. I’m guessing they have already been raised in a toast to Independence.

Michael Somare comes over. ‘Where have you been, Mark?’

‘Collecting the children. We had to park a long way away,’ I reply.

He looks down. ‘You kids are looking very hot.’ Two-year-old Damien looks up, ‘I want a drink.’

Somare responds, ‘Would you like a cold drink of lemonade?’ They all nod, ‘Yes, please.’

I thought he would signal a waiter but, before I can protest, he has gone. Two minutes later he’s back with drinks for the three of them.

So, who cares if we missed the actual moment of Independence? Of all that has happened this eventful day, for my wife and me, this simple act of kindness from the man who now leads the new nation of Papua New Guinea, will always be the most memorable.

Mark Lynch OL, ISO

Former Secretary to the NEC, 1975

Independence Day in Angoram

Angoram was one of the sites selected by Film Australia to be featured in a film to mark this important occasion in the life of the new nation. I worked as a teacher, inspector and educational administrator in PNG from 1963 to 1986.

Angoram was one of the sites selected by Film Australia to be featured in a film to mark this important occasion in the life of the new nation. I worked as a teacher, inspector and educational administrator in PNG from 1963 to 1986.

In our last year at Angoram—1975—Papua New Guinea celebrated its independence from Australia. In preparation, one of the junior kiaps, Dick Blackburn, went into Wewak and attended a workshop on the safe handling of fireworks, and at its end, was issued with a box of them to bring back. They were formidable, heavy-looking objects that had to be put out each day for a spell in the hot sun to be kept as dry as possible for the big night.

At sunset on 15 September, Independence Eve, John Blyth, the Assistant District Commissioner (ADC), had organised a simple but impressive ceremony around the flagpole outside the Sub-District Office. A solitary bugle played and the police lined up and saluted as the Australian flag was solemnly lowered for the very last time. A made-to-order breeze sprang up, and for a while, it did what flags are supposed to do—flutter and flap. No observer could miss the holes in the cloth that were made very obvious against the fading pink of the sunset.

After dark, the fireworks were let off out in the park/common in front of our house. We took our four-year-old, Sophy, out to see the spectacle. I had warned her of what to expect and Helen, my wife, Sophy, and I sat on a bank sufficiently far away from the launching place, my protective arm about my daughter. Despite her preparation, Sophy flinched in alarm beside me like a nervous little faun as each of the fireworks went off with a gut-wrenching thud. She enjoyed the new experience despite this.

Another flag ceremony was organised for the morning of Independence Day itself. The ADC, John Blyth, gave a speech to the large assembly. Then the new PNG flag, tied up in a bundle, was slowly hoisted on a temporary bamboo flagpole. When it reached the top, the halyard was given a sharp pull to break out the flag. However, all that happened was that the tip of the bamboo pole bent earthwards. Embarrassingly, the flag remained furled. Those aware of the deep symbolism of the occasion held their collective breath. To the relief of the breath-holders the flag soon displayed itself after a few more tugs, and a choir of schoolkids sang the National Song—‘This is our flag, etc …’—to welcome the striking new icon of the world’s newest state. A sing-sing followed by participating groups from up and down the Sepik.

The Muriks’ contribution was memorable. They performed a very balletic dance representing the flight of the sea hawk. Later, there were games—softball, soccer, canoe races, etc. A pig daubed with grease was released and squealed with alarm as it ran wildly about through the legs of the crowd, energetically eluding capture. Only when most of the grease had been rubbed off could someone maintain a grip on it and claim it as their prize.

We were told to expect a visit from the Prince of Wales on the day following. However, there was a late change of plans and instead of Prince Charles, our new Prime Minister, Sir Michael Somare, brought along Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara for the VIP visit. Sir Kamisese was the Prime Minister of Fiji and stood at two metres in height. I remember he gave a witty address, congratulating the PNG PM on PNG’s Independence, commenting that although quite tall, his country was small compared to the shorter Mr Somare’s country.

PAUL DENNETT

Prayers, Planes & a Prince

When in 1975 Gough Whitlam asked Michael Somare to provide a date for PNG Independence, Somare set the date and gave me the job of organising the events. We had two and a half months to do it, but getting people to join me in seeing the job done was difficult. It had to be a PNG show, yet there was no expertise amongst the indigenous people or government for it, and government departments were reluctant to release their more senior staff.

Also there were some early concerns over micro nationalistic movements that had sprung up, cults and also emotional talk from university students.

But when I had a general picture in my mind of the ceremonies that were required, the people to invite, the security, transport, accommodation, etc., I gathered a few staunch souls together and started on the detail. We raised funds from businesses, organised fireworks for each district and provided cash to make other district activities possible, paid for the West Indies Cricket Team to play in Port Moresby and Lae, had an Independence Medal made and issued all sorts of literature and badges.

During the six days of celebrations between 14 and 19 September there were exhibits, church services, sporting events, bands, pageants, formal addresses, dinners and ceremonies.

The two outstanding ceremonies in Port Moresby were the Flag Lowering Ceremony at sunset on 15 September and the Flag Raising Ceremony the next day. I selected the Sir Hubert Murray Stadium for the first—and that marvellous sunset, together with Sir John Guise’s words, ‘We are lowering this flag, not tearing it down’, made it a memorable occasion.

The Flag Raising Ceremony was conducted on Independence Hill, where there had been an anti-aircraft gun during the war.

At one minute past midnight on 16 Sept-ember, the Proclamation of Independence was announced by the Governor-General in a radio broadcast, followed by the National Anthem and a 101-gun salute provided by the RAN. At 9.30 am the Flag Raising Ceremony commenced.

Prince Charles inspected the Royal Guard before taking his place on the VIP dais. Cultural groups then handed the PNG flag to the Governor-General who then handed it to the Commander of the PNG Defence Force, asking him to raise it on behalf of the people of PNG. Two chaplains blessed the flag and it was raised at 10 am.

This was followed by a fly-past of RAAF and PNGDF aircraft. Prince Charles unveiled a plaque and then joined Sir John Guise and Sir John Kerr in planting trees to commemorate the occasion. The individual officers in charge of each official occasion all did very well and Government Departments—especially Public Works, the Government Printer, Department of Information—all rose to the great occasion.

David Marsh

PNG’s last District Commissioner

The Story of the Flag

The story of the crest and flag commenced during the life of the first House of Assembly when the Select Committee on Constitutional Development under the Chairmanship of the late Dr John Guise called upon the people and schools throughout PNG for submissions about their country’s flag. Hundreds of entries were submitted which, due to time restraints, were handed over to the Second Select Committee of Constitutional Development under the Chairmanship of the late Paulus Arek.

Armed with this information, the Committee in October 1970 had its executive staff analyse these designs to find the most suitable colours and symbols for a crest and flag. They found the popular colours were gold, green and blue and the symbols, birds, drums, spears and stars.

This information was passed to Hal Holman, an artist with the Department of Information and Extension Services, for him to design a crest and flag using these colours and symbols.

The committee ran with his designs – a tricolour flag in green, gold and blue with the Southern Cross and a white bird of paradise superimposed.

The committee divided into two groups to tour the country in January and February 1971. The people universally accepted the crest although there was some parochial discussion about the design of the spear and drum.

However, the people were quite outspoken when shown the proposed design for the flag. Mostly they regarded the design as a mechanically contrived outcome designed by the Select Committee and not produced by a real person. It lacked warmth and charisma. Our group visited Yule Island on 12 February 1971 where, at a meeting, a schoolgirl, Susan Karike, a pupil of the Catholic Mission School, gave me a revamped design of the proposed flag drawn on a page taken from an exercise book. It had instant appeal and I immediately thought, ‘This is the flag’.

Susan replaced the tricolour by making the lower segment of the flag black with the stars of the Southern Cross in white. The top segment was red with the stylised bird of paradise in gold. Susan described the colours as those most commonly used by the people in their traditional ceremonies.

The Committee next met in Port Moresby in March to consider the findings from its fact-finding tour and finalise its report. Both groups found that the proposed flag was not acceptable to the people as the flag for a future independent PNG, and decided to recommend one of the alternatives submitted during its tour.

The choice was narrowed down to two designs. Susan’s design I had already presented to the meeting. The other, somewhat larger, from a New Ireland group, was submitted by Mr Wally Lussick. The Committee adjourned that evening without having come to a decision. I felt a little despondent, as I needed more than a page from an exercise book to do full justice to Susan’s design. That evening Ross Johnson took the initiative and had his wife, Pat, put Susan’s design onto a piece of cloth slightly larger than a tea towel—see the photo of Ross and Pat with the first flag at the PNGAA Networking Meeting in May on page 12. When this was shown to the Committee next day a consensus was soon reached. Ross and Pat’s flag gave support to my presentation and the committee accepted Susan’s design.

The report was presented to and adopted by the House on 4 March 1971. It said this about the crest and flag:

The crest suggested by your Committee is acceptable to the majority of the people. Many groups particularly in the New Guinea Islands region, submitted that some object representing their particular area be represented on the crest, but it would not be practicable to include a representation from all areas on the crest. As there was widespread support for the crest as it stands, your Committee recommends that it be adopted.

The Committee has chosen a flag design submitted by a young Papuan girl named Susan Karike. In her submission to the Committee Susan described the colours of the flag as being the colours most commonly used by our people in their traditional ceremonies. The Committee recommends that this flag be adopted as the flag for Niugini.

I visited PNG in August 2003 and noted the respect shown to their flag. This reinforced that the decision we made was the correct one.

GEOFF LITTLER

Put PNG First: PNG atoa guna, putim PNG igo pas

It is with great anticipation and optimism we stand here to celebrate the 30th Independence Anniversary of Papua New Guinea in 2005. Our country has been described as the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of our South Pacific neighbours.

Papua New Guinea attained its Independence in 1975, from Australia under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. I was privileged to be just completing my university studies with many others in the likes of Mr Frank Kramer. Our pioneer politicians and public servants include our current Prime Minister, the Rt Hon. Sir Michael Somare, former

A Simbu boy rehearses for independence day celebrations in Port Moresby in 2005Prime Minister Sir Rabbie Namaliu and current Foreign Minister and former Prime Ministers, the Hon. Pius Wingti, Sir Julius Chan, and Sir Mekere Morauta. Independence was achieved with mixed feelings. Some critics say it was too early but be that as it may, it happened and it happened without any bloodshed as our first Governor General, Sir John Guise at the eve of Independence with the lowering of the Australian flag, and in handing the Australian Flag to the Australian Governor General Sir John Kerr, said: ‘We are lowering the flag and not tearing it down.’

Our 30th Independence motto challenges us to be patriotic in our outlook and calls for renewal and commitment and a beacon of hope; solidarity in our commitment for unity, and purpose for our nation, Papua New Guinea. We must now strive to excel in the things that bring positive outcomes and ensure we work towards protecting what we have already achieved and built over the last 30 years and continue to build on them. The vibrant parliamentary democracy and the government institutions, our diverse languages, cultural heritage, our unique environmental fauna and the virgin forest which we must treasure for future generations and not destroy for quick capital gains. We must not take these for granted but continue to nurture, protect and improve on them.

We have and will continue to have many challenges of nationhood as we have learned from the Bougainville experience. We must learn that ‘life is precious’ and that we can resolve differences between ourselves without resorting to violence. Today we celebrate ‘LIFE’; the life of Papua New Guineans and friends of PNG for the 30 years we have been together. Life, as you and I know, has many challenges, and PNG has had many such challenges, for example, the natural disasters of the tsunami, the frost and El-Nino; the Bougainville experience; the Sandline Crisis; economic short comings; the AIDS-HIV epidemic and others, but we will overcome such with equal determination and continue to strive to find solutions for the common good of our people.

What have we to look forward to in the next 20 to 30 years? By far the most significant will be the PNG Gas Project with the PNG to Queensland Gas Pipeline; the stability in our Parliamentary Democracy; the challenge to tackle AIDS-HIV, and improvement in both education and health, and the quality of life for our people.

We need to think and do things smartly and cultivate a hunger and thirst for excellence and Innovative thinking outside the box. As a Nation we must be ready to take proactive measures to embrace what is happening around us in regard to globalisation and to capitalise on opportunities presented to us for those of us living and working in Australia and vice versa.

We need to establish a mutually sustainable partnership between Australia and PNG at the community, corporate, political and bureaucratic levels. We must grab with both hands the opportunities presented by the Gas Pipeline Project and take a holistic approach on all fronts.

Queensland, the closest neighbour to PNG, provides great opportunity which my office is promoting with the State Development and Innovation Department, the QLD/PNG Chamber of Commerce, the QLD/PNG Business Corporation Group (BCG). We look forward to strengthening this relationship with further opportunities for PNG and Australia through the accessing of Labour Market Employment Opportunities in the horticultural sector and youth training.

Today we celebrate these and say ‘thank you’ to our mentor, friend and neighbour, Australia, for being a true friend during the Second World War when we stood side by side at the Kokoda Track Campaign and for the assistance over the last 30 years in the provision of aid and other assistance. Also, we acknowledge other donor countries who have and continue to assist us today.

Finally let me thank the PNGAA and its members for your great contribution to our country during your days in PNG and no doubt you will continue to maintain this link through your Association. I have read from your magazine, Una Voce, the many adventures and tasks that many of you accomplished whilst in PNG.

What can you do as friends and brothers and sisters of our people in PNG? Currently we are negotiating the seasonal labour opportunity for fruit picking and other employment opportunities in Australia. You have your networks, both through the Association and individually, to your representatives in the Parliament. Please, I urge you to support us in this, as this will make a tremendous difference for families if we are allowed to have these job opportunities. As you and I have learned from the media, the aid to PNG does not reach the families, whilst job opportunities will have immediate effect on family disposable income. I look forward to your support and hope we can once again stand side by side as we did at the ‘Kokoda Track Campaign’ when we needed each other. Thank you and God Bless You All.

PAUL NERAU LLBPNG

Consul General of Brisbane (2004–12)

PNG Flag Jump 2015

Governor-General Sir Paulias Matane meeting the teams at a sport to raise awareness against HIV/AIDS in Papua New Guinea, 2005

Soon after returning home in 1995 from completing Year 12 at High School in Brisbane, my daughter Melanie accepted a position as the first Supervisor of the Gold Club of the Lamana Hotel in Port Moresby.

After deciding to move to Australia, Melanie remained friends with the General Manager of the Lamana Hotel, Yiannis Nicolaou, and he told Melanie that the Minister for Sports had asked him to organise the 40th Anniversary celebrations the following year.

Yiannis proposed the idea of the ‘flag jump’ into the Sir John Guise Stadium as a spectacular highlight to the opening ceremonies and sought Melanie’s assistance.

Upon returning to Cairns, she contacted an associate who assisted in securing one of Australia’s top ‘skydivers’—Cameron ‘Coops’ Cooper, a veteran of 16 years of jumping. Coops had won a number of state and national awards. He was one of a handful of expert parachutists in Australia who could manage the proposed jump with a large flag. Melanie also contacted former Chief Instructor Glenn Bolton, one of only two accredited flag makers in Australia.

With specifications worked out he commenced creating the 14.4 m x 10.8 m (155.5 sq.m, or 1675 sq.ft) PNG flag weighing 20 kilograms.

Two smoke-bearers were also recruited for the event—Jeremy Roberts and Karl Eitrich. Meanwhile, in Moresby Yiannis was liaising with the Defence Force to make available one of their few aircraft for the jump. He secured the services of a PNGDF Arava transport aircraft.

As usual, during September along the Papuan coast, the south-east trade winds were generally blowing a gale most afternoons. The Ground Crew Assistant, Pepe Scoffel, had his work cut out assessing the winds to ensure compliance with safety standards. These required that winds not exceed 25 knots for a jump with such a large, cumbersome banner. Several practise/rehearsal jumps were aborted due to the strong winds before one was finally achieved. A further complication was that the official programme had the jump scheduled for late afternoon. This put the timing close to official ‘last-light’, before which both the aircraft and the parachutists had to be back on the ground.

As the aircraft circled in position from where the jump would commence, winds were still above 25 knots and gusting above 30 knots. Dusk was rapidly approaching with Coops and his team anxious not to disappoint the crowds that had made them feel so welcome and appreciative of their first exposure to PNG. The pilot announced one more circuit before the last-light equation forced his return to Jacksons and cautioned that winds were still above the limit but less than 30 knots. The trio jumped!

Chris Warrillow

Going Finish—My Favourite Treasure from PNG

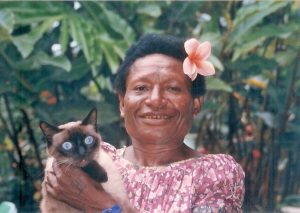

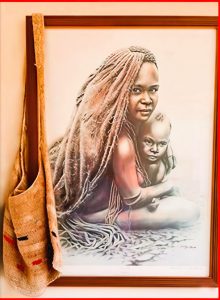

This Highland style bilum (above) was made in secret for me by my haus meri, Agnes, when she knew I would be ‘going pinis’. One of her main jobs had been to look after my beloved Siamese cats, Possum and Pixie. I was often away from Lae with my work, as was my husband.

This Highland style bilum (above) was made in secret for me by my haus meri, Agnes, when she knew I would be ‘going pinis’. One of her main jobs had been to look after my beloved Siamese cats, Possum and Pixie. I was often away from Lae with my work, as was my husband.

Over many weeks Agnes had combed out the loose fur from the cat brushes.

She cleverly wove the fur into the highland-style bilum. She was so proud to be able to tell me ‘gras bilong Possum’ and ‘gras bilong Pixie’.

It is far more than just a bilum, it is a token of love and loyalty from my humble haus meri. She didn’t have children herself and knew that, to me, my cats were the children I did not have. I would love to know if she still alive and around Lae.

It makes me very nostalgic for a time and place which only those who have lived there would ever understand. I have it casually draped over a framed, numbered print from an original painting by Steven Kawaie.

The hauntingly beautiful, framed print of the young Highland mother whose shy eyes really look at me, together with her baby, remind me of the loyalty and hard working women of PNG. He has captured the pure innocence and beauty of this young mother.

I pass these treasures several times a day and drift back in thoughts to the country and people with whom I was privileged to live for 26 years.

BEV MELROSE

Return to Papua New Guinea 49 Years On

Late in 2024, our elder daughter, Belinda, who was born at Port Moresby General Hospital in 1974, hinted that she would like to visit the place where she was born and asked if we would be interested in taking her and showing her around. Our other two children, Russell, who was born in Southport and spent his first few months in Port Moresby, and our daughter, Sarah, who was born in Dubbo, where we settled after ‘going finish’ in 1976, both joined the discussion.

I went to TP&NG in 1967 as a cartographer with the Department of Forests, working in various roles, mostly associated with forest assessment surveys and the mapping work involved.

My wife, Diane, had spent most of her life in PNG, except for attending boarding school in Sydney. Her father, Eric Flower, was in PNG with ANGAU during the war and, like many others, stayed on as a kiap. When he retired in 1975, he was the Co-ordinator of Capital Works in Treasury. Her mother, Jean, was in the WAAF and, at one time, was the personal secretary to Air Vice Marshal Cobby in Townsville.

Diane was a stenographer-secretary in various positions in Port Moresby and took down Sir Donald Cleland’s memoir in shorthand, then typed the draft. She was active in the CWA, the Victoria League and other voluntary organisations and, as the wife of a kiap on outstations, carried out all the usual unpaid tasks. Diane was a salary clerk in Forestry, where we met, and we married in 1968.

Plans were put into motion, and in June 2025, the five of us flew to Port Moresby, spent three nights there, and then went on to Rabaul for four nights before returning to Brisbane. Rabaul was important to see because Diane spent two years in Kokopo and two years in Rabaul between the ages of four and ten.

On the flight from Rabaul to Moresby we shared the plane with an NRL team from Minj who had flown in to play the local Gurias. They lost! When checking in at Tokua airport, the female staffer stood before the waiting queue and recited a prayer before issuing boarding passes. Where else in the world??

We stayed at the Airways Hotel in Port Moresby and the Rapopo Resort in Kokopo, both of which we highly recommend. In Moresby, we hired a minibus with a driver from Corps Security. It came with a security person, which was reassuring but ultimately unnecessary. They learnt much from our history. Security is a huge industry, even with government offices being fenced and under guard.

We visited all the well-known places, Bomana, Parliament House, the Nature Park, the museum, all of which are beautifully presented, plus some markets and Owers’ Corner. The displays in the museum are extraordinary, and Parliament House is quite spectacular. Visiting the United Church in Boroko, where we got married, brought back some memories.

At Parliament House, we were greeted at the top of the steps by a suited gentleman with a briefcase and an assistant who instructed the guide we were talking to ‘to show them through’, even though it was after hours. As it turned out, he was the Minister for Defence!

Our family was stunned at both Bomana and Bitapaka. At Bomana, it was moving to see the graves of two airmen whose remains were found recently on New Britain, 80 years later, and interred only weeks earlier.

At our old workplace, the staff were very welcoming and keen to talk about our time there.

While visiting the site of our old townhouse in Korobosea (it has been demolished), we spoke to the families living in the units behind. They were perplexed as to why these five white people were wandering around their neighbourhood, but when we explained that we had once lived there, they were very pleased to greet and talk.

The most outgoing of them was an artist named Clement Koys (Google him) who is the President of the PNG Art Society and has exhibited in Brisbane and Melbourne. He presented us with a beautiful portrait and said, ‘Thank you for coming back.’ Such generosity!

His father, Dennis, said the same as we left, noting that we had lived there in the good times. This sentiment was echoed several times during our travels. To our kids, the meeting with these people, their excitement and welcome, was a highlight of their PNG experience.

Port Moresby is a dynamic city, but poverty is still very evident, and a lot of rubbish is strewn around. We were pleased to have a driver as we would easily lose our way.

In Rabaul, we climbed Tavuvur, visited Bitapaka, explored tunnels, the underground hospital, museums, Yamamoto’s bunker, snorkelled, swam with dolphins and cruised the harbour. Nuigini Dive and Tour organised the lot very efficiently.

Diane’s old house on Namanula Hill is gone, but we enjoyed the beautiful views of the harbour, once known as the ‘Jewel of the Pacific’. Our driver found our stories so interesting that on day two, he brought his wife along for the day.

At all locations, the staff were attentive, well trained, courteous and eager to please. The people we met were friendly, curious and polite, just as we remembered. I doubt that we will return, as age creeps up, but I am sure our children will one day—to dive, to walk the track, and just to show thefamily. The experience was an eye-opener for them, and we are so pleased that we took the opportunity when we had it.

Our fond memories of life in PNG have been rekindled, and the way we were treated by those gentle people has reinforced our admiration for their beautiful country. We felt safe at all times.

We would be pleased to discuss our arrangements with anyone contemplating a visit.

Bob & Di McKeowen

bobanddimckeowen@bigpond.com