Medical Incidents

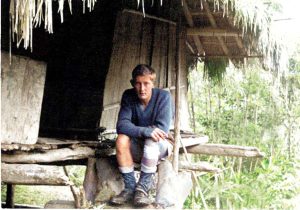

Peter Worsley

I spent about 18 months as Officer In Charge at Kalalo Patrol Post on the north coast of the Morobe District, 2,500 feet above sea level. My nearest airstrip was at Wasu on the coast, and getting there involved driving four and a half miles down a very steep, rough track in a Land Rover with chains on the wheels, as the track was very slippery. The only other Europeans at the post were a teacher, Bob Blanche, and his wife, Gloria, a trained nurse.

During my period there, I had a few medical experiences which are worth mentioning. One occurred in 1964 while I was on patrol in the Urawa and Yupna census divisions west of my post. At one village, I was shown a man who had been in a fight and had an arrow in his right thigh. The shaft of the arrow had broken off but the barbed point was very deep inside, in fact lying alongside his thigh bone. It had occurred a couple of days before and was obviously turning septic. None of their bush medicines were doing any good and the arrowhead needed to come out or the wound would rapidly kill him. I always took a first aid kit with me on patrol but it was very limited. I certainly had no anaesthetics.

The wounded man wanted something done and I knew that it would be too late for him if he had to go to Kalalo and get a plane from there to the hospital in Lae. It would have taken at least five days to walk to Kalalo, certainly much longer if he had to be carried on a stretcher. This was highly probable as he was already having great difficulty walking. As usual, I was completely out of touch with anyone while on patrol as we did not carry radios, so getting advice from a doctor was out of the question. I decided to have a go at getting the arrowhead out. This required an operation.

I had a sharp scalpel, a pair of tweezers, a needle and cotton (for sewing on buttons and repairing tears in clothing), some sulpha powder (my only antibiotic), some methylated spirits (used for lighting my lamp) to wash and disinfect the wound and some rum as a sort of anaesthetic! I first poured a large mug of rum and gave it to the patient, telling him to drink it as quickly as possible. I had already explained to him that this was the only ‘anaesthetic’ I could give him. I then washed the wound with the methylated spirits and commenced cutting down through the muscle of his thigh towards the thigh bone and the arrowhead. I was scared that I might cut an artery and that he would bleed to death, so every cut was only a millimetre deep. Eventually, after literally cutting down to his thigh bone, I managed to get hold of the piece of arrow and pull it out. Numerous splinters of wood and bone (the arrowhead was partly bone) also had to be cleaned out. I washed the wound in methylated spirits, packed it with sulpha powder, sewed a couple of stitches to keep it more or less closed and put a bandage on it.

I then detailed some men to take him to Kalalo as quickly as possible so that Gloria Blanche could check him and get a plane to get him to hospital. Throughout the operation, the patient just sat there watching what was going on, never once complaining or giving any indication that it hurt. I am proud to say he made a complete recovery. It was sometime later that I started to wonder what would have happened to me if the patient had died during the operation. I might have been in considerable trouble then! The incident of my operation on the man’s leg brought out the fact that the people generally showed little reaction to pain. Naturally, they felt the pain but because most other people in the village offered little sympathy they did not show much reaction. This was combined with the men’s idea of toughness and the ‘macho’ image of strength and fortitude.

A typical example is of the man who came to my house at Kalalo one Sunday full of apologies for disturbing me on my day off. He was cutting firewood down at Wasu and had cut right through his ankle and his foot was only held on by a bit of skin and flesh on the outside. He had strapped the foot up to the bottom of his leg with some vines and walked up to an altitude of 2,500 feet along four and a half miles of very rough road to me for help. I hastily radioed for a plane and he was taken to Lae. He survived but I think he lost his foot. Sewing severed limbs back on wasn’t as common or as possible in those days, particularly in little remote towns like Lae in New Guinea. •