Exploring New Guinea in the 1930s

S Warren Carey AO

In September 1934, any thought of going to New Guinea had never entered my mind. I was well settled in my geological field work in the Werris Creek region and was planning on applying to go to Cambridge University in England to complete my education with a doctorate.

Meanwhile, geologist and geographer, GAV Stanley with surveyor, HD Eve, had returned to Sydney from two years geological survey in New Guinea on behalf of Oil Search Ltd. The company planned to increase its activity by adding three more geologists and another surveyor. Stanley approached me, for although I had not specially trained in petroleum geology, I had first-class experience in structural and stratigraphic mapping, which was what the company really needed.

I agreed to go with him to the Oil Search Ltd office, and I spent a couple of hours with him and with Eve, looking at their maps and discussing in detail their field methods and their relations with the native population.

Field work alone in mountainous country and wilderness had always stimulated me and I had found enjoyment and contentment camping in the bush. It was the country work off the beaten track which had attracted me to geology in the first place. I was a field geologist at heart, not a laboratory scientist. Cambridge meant three years of lab-work. New Guinea meant jungle geology and adventure of the highest degree.

The salary was 250 pounds per year, but all field costs were met by the company. However, it was agreed to grant me an extra 300 pounds a year as honorarium because of my M.Sc. qualifications in structural geology, but in no circumstances was I to inform the others.

Two weeks later our party sailed on SS Montoro on her three-weeks’ cruise via Brisbane, Townsville, Cairns, Port Moresby, Samarai, Rabaul, Kavieng, Madang and finally to Boram Copra Plantation, where we were landed by lighters.

The party consisted of JN Montgomery (a former Anglo-Persian Oil Company geologist), GAV Stanley, AKM Edwards (geologist), HAJ Fryer (surveyor), and me.

Most of the party sailed from Boram to Matapau on an island schooner, but Stanley and I surveyed the 50-mile coast from Boram to Matapau—the place where oil had been found decades before, seeping out from faults in epidiorite, so it was a logical place for our base.

The Mandated Territory

In 1919, Australia was granted the mandate to administer the former German New Guinea colony, which included the northeast sector of the New Guinea mainland, and the offshore islands of the Admiralty Group, New Britain, New Ireland, and the northern Solomon Islands, but several years were needed to set up the administration and establish effective control over those areas previously controlled by the Germans.

When I started in the Sepik district in 1934, government officers patrolled the coastal zone and foothills, but administrative control had not extended over the Torricelli and Prince Alexander Mountains, where I started mapping. We were therefore granted special permits to enter and operate in ‘uncontrolled’ areas.

To go to a place a hundred kilometres away, I walked. Leaving base camp, I would not expect to see another white man for several weeks, only neo-lithic natives, many of whom had not seen a white man before. There would be no replenishment of supplies of any kind. The only fresh meat was what I shot. I kept a working yeast bottle to leaven my bread. No base maps—I knew where I was because I had surveyed it, and tomorrow’s work would be in uncharted country.

If something went wrong with my instruments, clothes, boots, rifle, canoes—if I couldn’t fix it, it wasn’t fixed. If I, or one of my natives got sick, or wounded, or broke a bone—if I couldn’t fix it, it wasn’t fixed. The nearest medical help was weeks away!

Mail from home or company headquarters, or newspapers reached Matapau base once in six weeks, already two months old, and a couple of weeks later would filter through to me. There was no radio communication, or news broadcasts (we had no broadcast receivers), and air support was not even contemplated.

Each of us would leave base on an exploration circuit lasting four to ten weeks, during which our only contact with each other or with base would be occasionally by a native messenger travelling a day or two to the other party. There were no other Europeans in the region.

My field party would consist typically of about 30 native labourers, signed on to work for two years—boss-boy, personal servant, a survey team of seven (one to carry the plane table, one to carry the telescopic alidade and umbrella—essential to keep rain off the plane table), two survey staff men, two cutters, and my bearer (carrying my rifle, hand instruments, hammer, and notebook), and about 21 carriers, three of whom would have shotguns to hunt for a wild pig or cassowary while the others set up camp. Each labourer carried an 18-inch bush knife, and two an axe.

Equipment consisted of an 18×18 ft canvas fly; my bed-roll; my canvas bath (3×3 ft and 10 inches deep), and one patrol-box containing my clothes, toilet needs, books, alarm clock, torch, mending kit, drafting instruments. Another patrol-box contained my table utensils and tablecloth; another contained food mostly canned, and another contained kitchen utensils, with another containing Tilley lamp, methylated spirits, kerosene, Salter spring balance, bullets for my rifle, revolver and shot-guns, cod-liver oil for weekly issue to labourers, black-twist tobacco likewise.

There was also a medical chest, a map cylinder containing used field sheets and spare field sheets, a folding table, a folding chair, a camp oven and about three 50 lb bags of rice and about three 50 lb bags of blue peas—as labourers’ rations when food is not obtainable from local natives, one box of trade items—salt, beads, etc. There was also a box of canned bully beef, in case I had difficulty in shooting enough game for the meat ration of the labourers.

During one of my explorations, shortly before midday on 20 September 1935, I was surveying down the Sibi River in the Wapi country south of the Torricelli Mountains when the most violent earthquake, at 6.3 magnitude, in New Guinea recorded history struck. The shallow focus was not far below us. My terrified survey labourers were thrown down, rose, to be thrown again, and again. Trees were falling all about. Ridges were splitting and roaring down like avalanches. The survey station I had just left was buried tens of metres deep as the cliffs above erupted over it. A second earthquake followed about half an hour later, severe, but less intense than the first. After-shocks continued all that day and during the night, but it was a couple of months before the country settled down.

Many natives perished, some buried under landslides, others killed by falling timber, and at least one group were drowned in the flood of a collapsed dam. Villages are mostly on ridgetops, many of which split, with grabens taking houses down, some with people in them. One village slid down into a series of terraces, and villagers strung corpses from coconut palms to purify and scare the devils who had caused the ’quake.

Returning a few weeks after the ’quake, we discovered that the entire length of the Torricelli Range was denuded of its topsoil and timber.

The Papuan Delta

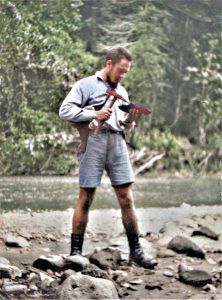

The team at Era Base Camp—Sam Carey (left), Norm Pratt, Bruce Hides, Wilson, JC Pratt, J McKinnon and JN Montgomery (seated)

In 1937 I had left the Mandated Territory after some two years there, and was working in the Papuan Delta. When we arrived at the Era Base Camp—where the team members included Norman Pratt, Bruce Hides, JC Pratt, J McKinnon and the Field Manager, JN Montgomery—Pratt and Wilson were sent up the Era River to set up camp at Woodward’s Junction, where the Era divides into the Mena River to the northeast and the Upper Era to the west.

For the first six miles we travelled by motor canoe until a bar of brown coal crosses the river. From there the river crosses the strike of the Miocene sandstones and shales in a series of rapids for two miles to Woodward’s Junction. So, we left the motor canoes just below the coal seam, and established a depot there, and dragged the paddle canoes around each sandstone bar rapid in turn, to get to Woodward’s Junction where we established camp. I was with them for a couple of weeks to help them get started, before returning to Era Base to prepare my own expedition up the Upper Era.

But then the guba struck!

A guba is a line-squall or tornado which is common in the Gulf of Papua and Port Moresby. It can be very destructive along its path which may be 100 metres or less wide. Wind velocities become very high, 150 km per hour and more, so that it snaps off and flattens a swathe of quite large trees. Such a guba cut through the Era Base Camp about 8 pm that night, brought down several trees which flattened our mess hut and kitchen and part of the long native labour house.

Later, the base camp was moved to the Purari River just below the Bevan Rapids as this was the limit of navigation to small craft. Porterage and dragging of canoes was required above this site.

I continued working for Oil Search Ltd until 1938, working on the Aure, Erave and Itave Rivers (above Hathor Gorge) and made a trek up the Vailala River, crossing the divide to the Tauri River and down to Kerema. Subsequently, I was senior geologist with the Australian Petroleum Company (APC) until the intervention of war in 1942. •

About the Author

Samuel Warren Carey AO (1911–2002), Professor of Geology at the University of Tasmania from 1946 until his retirement in 1976, was internationally acknowledged as a controversial extrovert in global tectonics, who vigorously expounded and defended his belief in earth expansion.

This article and photographs (now colourised) were supplied by his son, Harley Carey, from the many notes his father wrote on his experiences.