Department of Agriculture, Stock & Fisheries, Taliligap, Rabaul

Part Three – Peter Stace & JW (Bill) Gornall

The Gateway for new rural development officers (didiman) to the PNG islands:

Personal Experiences in 1967

Parts One and Two of this article focused on the history of DASF Taliligap and how Bill and I were introduced to the realities of agriculture and culture, important elements in our work. Part Three is the final instalment of this series.

Coconut Production

Coconuts and copra production was the first cash crop in most coastal areas of Papua New Guinea. Copra, being the dried coconut flesh, was sought after by early European traders for the production of coconut oil, a product that was, and is still, used for soap, margarine, ice cream and cooking. In the 1800s the world demand for vegetable oils and coconut oil was high. As early as the mid-1870s, traders were buying coconuts from the Tolai for the production of copra.

Emma Forsayth of Samoa, née Coe, widely known as Queen Emma of New Guinea after about 1890 (Robson: 1979, p 7), took her first long look at eastern New Britain about 1878. The Godeffroy men, German traders with a schooner in the area, showed the natives how to dry coconut kernels and make copra (Robson: 1979, pp 96–7). In New Guinea in 1882, Emma’s brother-in-law, RHR Parkinson (who married her sister Phoebe Coe), joined her. Together they planned Ralum (near Kokopo on the Gazelle Peninsula) as the centre of a wide area of inter-related plantations. By 1885 their coconut plantations extended for miles around Ralum (Robson: 1979, pp 164-5).

The German administration of New Guinea was established in 1885, and one of its objectives was the production of copra sourced from indigenous farmer-grown coconuts, and later from commercial plantations that were established on the Gazelle Peninsula and other areas of coastal New Guinea. Copra plantations have been cultivated since the late 19th century, originally by German colonialists. Following World War I, these plantations continued under Australian interests, managed by companies such as Burns Philp, WR Carpenter & Co. and Steamships Trading Co., to name a few, as well as individuals.

When we RDOs were learning on the job, marketing of copra was well established through the Copra Marketing Board (CMB) and privately owned trade stores. The CMB bought copra by the bag, whilst trade stores were set up to purchase small quantities from growers. Traders would re-pack these small quantities of copra into bigger lots and onsell to the CMB at a profit. We were introduced to CMB staff and shown the big copra shed piled high with bagged copra waiting to be shipped overseas. The process of marketing large or small volumes of copra was well established by the mid-1960s (Jackman: 1988).

Domestic Use of Coconuts

Domestic consumption of coconuts is a major use of coconuts in PNG, and coconut milk is a principal ingredient in many Melanesian culinary recipes. Coconut milk is made from coconut flesh when it is grated and squeezed to extract the juice. This coconut juice or milk is used to boil vegetables, taro, sweet potatoes, fish and pork. It is also used in the famous mumu, where meat, taro and other vegetables, and coconut milk, are wrapped and tied in banana leaves and cooked in a hot pit. The mumu bundles are put into a pit and covered with hot stones, soil and wet bags, and left for hours. When the bundles are removed from the pit, the resultant meal is a gourmet dish, PNG-style. A mumu meal offers a lifetime of powerful memories, thanks to the flavours of coconut.

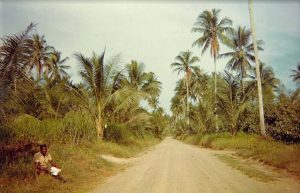

One of the first aspects of coconut production we learnt was that coconut palms should be planted 27 feet apart. This method was the basis for coconut plantations and new village plantings. And yet, as we travelled around the Gazelle Peninsula, the first village we came to showed coconut palms growing like a planted forest. Individual palms of all ages were planted really close together.

An explanation was provided by agricultural assistant, Kepas, Taliligap’s residential Tolai cultural staff member, who said:

With the matrilineal inheritance of the Tolai, there may be two or more people with legitimate rights to grow a garden on a piece of land. In a short-term food garden, each person may plant their garden at different times with no problems. However, coconuts are a long-term crop, and each legitimate person plants their own coconuts, resulting in lots of palms on a piece of land.

Then the next generation may come along, and the younger person who also has some traditional rights, plants their own palms. The result is a forest of palms with limited production, but everyone is happy (maybe).

Kepas showed us how cultural values were more important than the best economic model for agriculture.

Livestock Production

Livestock production on the Gazelle Peninsula was mainly free-range pigs and poultry, where animals were allowed to scavenge around the villages. They were fed food scraps and used coconut scrapings to keep the animals close to their owners. When found, chook eggs were collected, and fowls and pigs were slaughtered as required.

Road-scape of rural Gazelle Peninsula showing coconuts of various ages and planting densities (Photo by Bill Gornall 1967)

Sometimes, day-old chickens were ordered from hatcheries in Australia or Port Moresby and paid for through the DASF office. These chicks were fed scraps and commercial feed and raised to a slaughter weight. When the birds were ready, they were sold through the market or prepared for a special cultural event or singsing. Animal protein (except fish) was essentially kept for special occasions and represented a small but very important element of agricultural activities.

Pidgin English (Neo-Melanesian—Tok Pisin) was a widely used language amongst many of PNG’s people, especially in New Guinea but also in some parts of Papua. It followed then that for field officers in particular, to converse with people in a country where its inhabitants spoke some 800 different languages, the widely used Pidgin English should be learned. So our introduction to Tok Pisin was at a course in Taliligap run by Geoff Gaskill. Our future field postings provided the majority of our education in this endeavour.

All too soon, following our short orientation at Taliligap, we were posted to various locations in the New Guinea Islands to learn our profession ‘on the job’. Bill was posted to Talasea, West New Britain in July 1967 and in November to Kandrian, WNB. Peter was posted to Kavieng in New Ireland in July the same year and in January 1968 to Hoskins, WNB, the start of the Oil Palm scheme.

The first address that parents and friends of many new didiman would address their letters to was: DASF, Taliligap, Rabaul, East New Britain, Territory of Papua New Guinea. Taliligap remains a powerful recollection of Papua New Guinea for expatriate men and women who went to PNG as agriculturists.

References

Jackman, HH, 1988, Copra marketing and price stabilization in Papua New Guinea: a history to 1975, National Centre for Development Studies, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU Press, Canberra. Available online through Open Research Repository at ANU.

Robson, RW, 1979, Queen Emma: the Samoan-American girl who founded an empire in 19th century New Guinea, Pacific Publications, Sydney.