Department of Agriculture, Stock & Fisheries, Taliligap, Rabaul

Part Two: Peter Stace & JW (Bill) Gornall

The Gateway for New Rural Development Officers (didiman) to the PNG islands: Personal Experiences in 1967

Part One of this article focussed on the history of DASF Taliligap and how Peter and Bill were introduced to the realities of agriculture and culture, important elements in our work. Part Two covers our continued learning experience of cocoa, the Rabaul market and livestock production, all of which were part of our orientation as didiman in the PNG Islands.

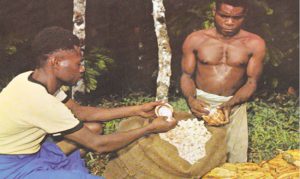

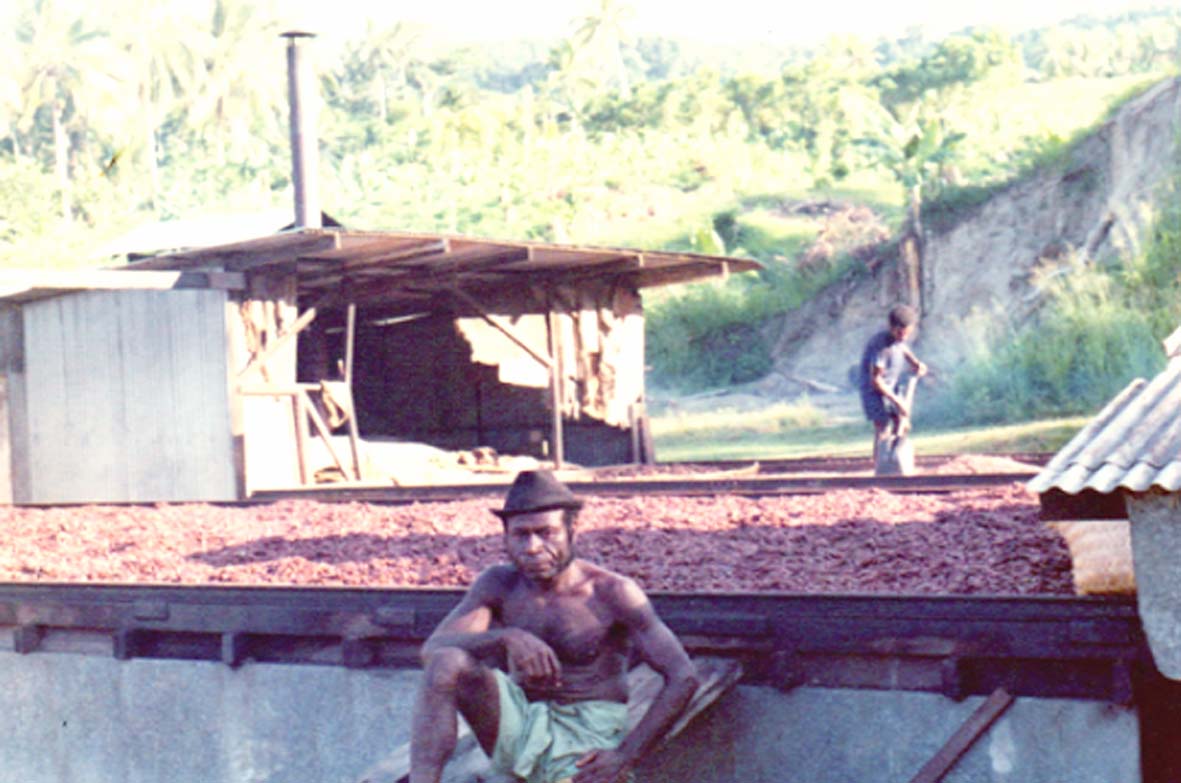

Cocoa Production

Cocoa was an important cash crop since it was introduced by the German administration prior to WWI; however, cocoa dieback, a disease that affects the growing branches of the cocoa tree, had recently become a serious problem. Cocoa trees were dying, seriously reducing production, and the disease was spreading at an alarming rate across the Gazelle Peninsula. Bill recorded in his Field Officers Journal:

…At Gela Gela, staff including agricultural assistant Wilson and some farmer trainees, counted 278 cocoa trees in a village plantation of 1000 trees that had been infected with die back [sic] disease within a fortnight…

Plant pathologists at LAES Keravat were identifying the causative agent, a fungus that was attacking the growing shoots and branches of the cocoa tree. For years to come, dieback in cocoa trees affected this lucrative cash crop. Suggestions of pruning affected branches and burning the prunings, along with fungicide spraying and planting of alternative crops such as pepper and other spices, were being presented, with little success. Dieback was devastating cocoa production on the Gazelle Peninsula. It was the sound research at LAES Keravat that came up with a possible solution for genetic resistance to dieback; but that came much later.

RDOs, or didiman, at DASF Taliligap learned much about cocoa tree dieback as well as cocoa management techniques and cocoa bean fermentation and drying.

The Tolai Cocoa Project

The Tolai Cocoa Project (TCP) on the Gazelle Peninsula was developed to centralise and standardise the fermenting, drying and marketing of large volumes of village-grown cocoa. The TCP had been active since the early to mid-1950s and by 1967 had grown to cover a large proportion of cocoa production on the Gazelle Peninsula. The TCP was implemented in collaboration with, but not part, of Gazelle Peninsula’s Local Government system.

The TCP offered many benefits, such as fermentation, drying and marketing of the cocoa beans to maximise the best quality and present a more consistent product. Because cocoa sale lots were significant, market leverage saw cocoa buyers paying top prices, leading to a promising future for village cocoa producers. (For further reading on the history of the Tolai Cocoa Project see Epstein: 1968).

On one occasion Peter accompanied Don Shepherd from DASF in Rabaul on a wet-bean cocoa-buying excursion. They travelled with staff from the TCP by truck with a bag of money, driving out to villages where wet cocoa beans were stacked in bags and baskets on the side of the road. Each bag or basket was weighed and cash was handed to the owner. The wet cocoa beans were then put on the back of the truck and later taken to a central fermentary and drying location for processing. It was a great and interesting experience.

On this excursion, men would occasionally emerge from the bush, throw rocks at the truck, shouting abuse and then disappear. The DASF visitors were told not to worry: ‘em raskol tasol. Yu no inap long wori’—‘these men are just rogues, don’t worry.’ Don Shepherd was not at all concerned, continuing to hand out money for wet cocoa beans. As a newcomer, Peter thought it was great as large quantities of money were being handed out to the village cocoa growers. What’s wrong with that?

Bill had a similar experience when he was seconded to Taliligap from Kandrian in West New Britain to support the TCP. In his Field Operating Journal of August 1970, Bill recorded that he:

… visited villages to seek out leaders for meetings to explain the concept of the Tolai Cocoa Project. Subsequently, we held many meetings. Attendances ranged in number between 15 and 200 people. Some meetings were quiet but others rowdy. At one meeting not far from Taliligap, stones rained down on the meeting roof …

Peter returned to Taliligap as Officer in Charge in 1974-75 and the following is included to give a broader perspective.

It turned out that both the local government councils and the TCP were developments initiated with good intent by the Australian administration. They were great ideas and similar concepts worked well in Australia, but not necessarily on the Gazelle Peninsula. ‘Some’ in the Tolai community held a difference of opinion to the Australian administration. Political values based on Tolai cultural norms, the authority of the village ‘Big Men’, and the Tolai matrilineal land inheritance system, were being challenged. There were, however, many Tolai cocoa growers who were very loyal and supported the TCP.

Kepas, an agricultural assistant and a local Tolai, who worked at Taliligap, said: ‘kaunsil na kakao project (TCP) em tupela em i brukim tabu (pronounced tambu) belong ples.’—‘Both the council and the Tolai Cocoa Project are breaking the traditional rules and values of Tolai culture.’ At the time Peter did not understand what Kepas meant. Subsequently he realised that both the TCP and local government councils were not completely in line with traditional political systems. These indigenous systems were based on the ‘Big Man’ system. Because of this discord there was a degree of mistrust among some in the Tolai community, especially with the TCP.

Due to unease and a growing concern about the Australian administration, the Mataungan Association was formed by politically aware locals to support the traditional values of some of the Tolai communities, with regards to local councils and the TCP. This is a very complex topic, however, and won’t be dealt with in this article.

In summary, as young didiman recruits at DASF Taliligap in 1967, Peter and Bill were introduced to indigenous political and cultural values but they came to realise that Australian administration policies were not always well-aligned. ‘What! We Australians were getting it wrong? Ugggh, that was a big learning experience.’ Irrespective of any mistakes made by the Australian administration, the TCP was highly instrumental in developing a dynamic and valuable cocoa industry on the Gazelle Peninsula.

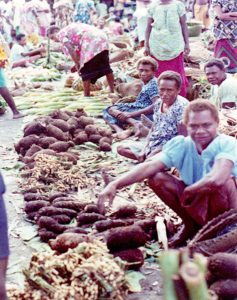

Rabaul Market

Whilst at Taliligap, Peter and Bill were advised to observe and utilise the local markets for a number of reasons. Markets are a good indication of what foodstuffs are available and as new RDOs they could pick up on social issues. Markets are also a great place for gossip and finding out what was happening around the place. Local markets are a great source of fresh fruit and vegetables—eat local and see what the farmers are doing.

Rabaul’s Saturday morning market, on the corner of Malaguna Road and Mango Avenue, was an experience Peter and Bill were told not to miss, as it was a perfect example of markets—PNG style. In 1967, the Rabaul Market was full of dynamic and active vendors and buyers. There were two main areas at the Rabaul Market, the first being where indigenous food was sold. There was great variety, including vegetables such as taro, sweet potato, tapioca, yam, aibika, pitpit and kumu (edible leaves) and fruit such as mango, banana, pineapple and pawpaw. Nuts sold were, of course, coconuts but others too, galip nuts and peanuts being much sought after. Handmade baskets and clothing and large quantities of betelnut or buai (from the palm Areca catechu) were also sold. Many Papua New Guineans really enjoy their buai, giving them a feeling of well-being. The red stain of buai spit was splattered all over the place and its smell wafted in the tropical breeze. Newcomers often found buai chewing disgusting but soon realised it was just a part of PNG life.

The market was an outlet for many vendors, each selling their own produce or product. Some moved only a small volume of produce whilst others offered goods or food in larger quantities.

In 1967, produce was gathered into small bundles and valued at 10¢ a bundle. The price would not change irrespective of how quickly or slowly the item/s sold. There was no bargaining and the price asked for was paid. By 1967, Australian currency was legal tender, as well as the highly treasured shell money or Tabu (pronounced Tambu: a different meaning to tabu meaning kastom, or tradition).

Tabu shell money was highly valued, and accepted as a medium of exchange to buy anything. At the time, an equivalent 10¢ in Tabu was about 10–12 small shells on a string of cane.

The common use of Tabu was an example of how important traditional cultural values were, and remain so for the Tolai. It reflected the values didiman needed to appreciate in their work, irrespective of posting. Tabu is still greatly valued by the Tolai (Sieber: nd).

The other market area focussed on produce sought after by the Chinese and Europeans. Crops such as tomatoes, lettuce and other leafy vegetables, pumpkins, lemons, limes, pineapples and pawpaw were all available. This area tended to be a little more orderly but still attracted the lively market atmosphere and the unmistakeable smell of buai permeated throughout.

Other traded items included handcrafts, especially woven baskets, bilums and carvings, clothing such as colourful laplaps and blouses, and ornamentals, including necklaces, bangles and other trinkets.

The Rabaul Market offered significant training opportunities for RDO recruits. Peter and Bill learnt to appreciate Melanesian foods and food crops important for subsistence gardening in village life (Epstein: 1968). •