A Project to Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Independence

Tim Griffiths

For some years Tim has been involved in a PNG heritage project. His goal is to celebrate the anniversary of independence with an installation in regional centres of interpretive panels displaying historic photographs depicting village life 100 years ago. A successful prototype panel was installed at Lake Murray, Western Province, in 2017. To tell the story behind that installation we must go back 103 years …

Following Frank Hurley’s 1922 Expedition to Lake Murray

When world famous photographer Frank Hurley and Australian Museum scientist Alan McCulloch sailed their ketch Eureka into Port Moresby’s Fairfax Harbour in December 1922, they had every reason to feel pleased with themselves. They had penetrated the interior of Papua by journeying up the Fly and Strickland Rivers into Lake Murray. They succeeded in achieving ‘first contact’ with headhunting tribes in the upper reaches of Lake Murray.

The expedition had assembled an extensive collection of artefacts, including intricately decorated and stuffed human heads, and Hurley had obtained hundreds of glass plate negatives. His photographs captured the diversity of the peoples in the Gulf and Western Province. Hurley photographed ravis (men’s houses), some over 400 feet long and 70 feet high, which no longer exist except in his photographs. Hurley even made the first aircraft journey in the country when he flew from Port Moresby to join up with the Eureka at Daru. His flying boat, Seagull, was typical of aircraft at the time, constructed of timber, canvas and wire, with an open-air cockpit, travelling at an average speed of about 95 kilometres an hour.

Imagine Hurley’s surprise when the Government welcoming party at the main wharf came on board and seized the entire artefact collection, despite Hurley and McCulloch holding collection permits. The administration announced an official inquiry into allegations of improper collecting methods, intimidation and use of force. Witness statements were obtained. Hurley denied the allegations and denounced the Lieutenant Governor Sir Hubert Murray in the Sun Newspaper in Australia for preventing the collection being seen by the public.

Whilst the artefacts were intended for the Australian Museum in Sydney, Hurley was first and foremost a commercial man. Some of the artefacts were wanted as props for the release of his film, Pearls and Savages.

Ultimately, most of the artefacts were released to the Australian Museum where they became a key part of its Pacific culture display. Sir Hubert Murray was unforgiving and refused Hurley permission to re-enter Papua to make two feature films. Hurley went instead to Merauke in Dutch New Guinea.

Ninety-five years later, in November 2017, anthropologist, Dr Jim Specht, Tim and Jenny Griffiths, film maker Alex George and ABC journalist Catherine Graue set out from Port Moresby to retrace the route taken by Hurley and McCulloch.

They took with them an interpretive panel made of stainless steel and aluminium on which several of Hurley’s Lake Murray photographs were enlarged and printed in high resolution. Most people in Lake Murray had never seen Frank Hurley’s photographs of their ancestors. The panel also contained a short story written in English and Tok Ples, telling of the historic meeting in 1922 between Hurley and the people of the lake. Once assembled, the panel stood three metres high and three metres wide.

Even today, Lake Murray, in the remote Western Province of Papua New Guinea, remains isolated. There are no connecting roads or regular airline passenger services. Consort Shipping runs cargo vessels up the Fly River to service Ok Tedi Mine and generously offered the group passage on its vessel Kiwai Chief.

Setting out from Port Moresby at the end of October 2017, the Kiwai Chief enjoyed a calm crossing of the Gulf of Papua and spectacular red sky sunsets. Approaching the Fly River delta, they found the water had turned brown with sediment. Uprooted sago and nipa palm trees (Nypa fruticans) drifted out into the current, an issue that would have created navigation hazards for the Eureka, but not the Kiwai Chief. The delta itself is 100 kilometres wide, braided with channels and islands. The Fly River starts over 1,000 kilometres to the north in the central highlands and powerfully snakes its way across flat savannah and floodplain. Whole islands of grass and trees come floating down the river.

Expedition crew: Jenny Griffiths third from the right, Tim Griffiths on Jenny’s left. Dr Jim Specht in foreground

On the fourth day, the Kiwai Chief reached Everill Junction where the Fly and Strickland Rivers converge. From there, Ok Tedi Development Foundation provided the expedition with a fast-moving ‘banana boat’ to travel up the Strickland and into the very pretty Herbert River. The Herbert, fed by Lake Murray, disappears into tall reeds and giant lotus lilies masking the entrance to Lake Murray. The lake is a huge body of water studded with low-lying islands. After the wet season, it grows to about 2,000 square kilometres, a paradise for birdwatchers and fishermen.

Hurley’s 1922 diary describes how the inhabitants fled their villages as soon as they saw Eureka steaming across the lake.

After two frustrating weeks, Hurley ‘collected’ artefacts but was unable to make contact with the ‘headhunters’ he desperately wanted to film. About to give up, Hurley and his crew pursued a

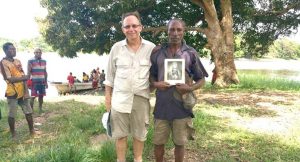

David, an Usakof man with Tim Griffiths, holds Frank Hurley’s 1922 photograph of his ancestor, Musje. Hurley incorrectly named this man Homoji—photo taken in 2016

distant boat that was spied disappearing into a dense thicket of tall reeds. Nearby, they were attracted to an abandoned log canoe full of artefacts and booty.

In his diary, Hurley congratulated himself on his good fortune. He called out the only Tok Ples word he knows, ‘sambio!!’. The word meant peace. The canoe they had pursued was paddled out from the reeds. The tribesmen on board replied, ‘sambio’, but Hurley had fallen into a dangerous trap. The canoe was a ruse. Suddenly, hundreds of warriors emerged from the tall reeds, their canoes quickly surrounding the Eureka. It was a moment of high drama; both sides were armed. McCulloch skilfully defused the situation, and soon an exchange and trading of goods was underway with the people of the lake. Hurley got his photographs of the warriors, and he kept his head.

Hurley’s diary records meeting the chief of these tribesmen, a man called Homoji from a village called Dukoif. No such village exists.

On a previous trip to Lake Murray, Tim had visited the island of Usakof which he surmised was the location of Hurley’s encounter.

The villagers of Usakof were familiar with the story of Hurley. One of the villagers produced a stained photograph of his great-grandfather, Musje. The subject of this photograph looks proud and self assured. The front half of his head is shaved while the back has long ‘Rastafarian’ style locks with straw extensions. It was in fact Hurley’s photograph taken of the chief whom Hurley misdescribed as ‘Homoji’.

After three days of talks with villagers at Usakof and nearby Boboa, the interpretive panel was assembled, erected and formally unveiled at Lake Murray Station on 6 November 2017. Several hundred villagers attended these meetings.

The 2017 expedition team should not have been surprised by the first two questions from the elders. ‘Does the Australian Museum still have the artefacts taken by Hurley?’ and ‘Can we get them back?’

The repatriation of artefacts is a complex issue. It usually involves a return to a well-resourced Museum. It was the next question from the Lake Murray elders, however, which was completely unexpected. ‘Musje was a great chief but he disappeared after Hurley came. Did Frank Hurley kill Musje or take him away on his boat?’

There was no satisfactory answer to the question. Musje was photographed on board the Eureka but there is no suggestion in the diaries that he remained on board. It is a puzzling gap in the oral history. However, oral history varies depending on who is doing the telling, and each Lake Murray clan has a different version of events. More than one clan claims ancestral connection to Musje.

The interpretive panel was welcomed by the people of Lake Murray as educational for the younger generation. It also provides a lasting opportunity for cultural tourism. The Australian Museum holds photographs which Hurley took throughout Papua, including in the Gulf, Oro, Milne Bay and Central Provinces as well as Hanuabada. With support from the Museum and the PNG National Cultural Commission Tim has applied for Commonwealth funding to do similar installations in each of these areas. If you would like to be a project sponsor or assist with the installations, please contact Tim directly. Email tgriffiths217@gmail.com •

Editor’s Note: Photos courtesy of Tim Griffiths, a Sydney lawyer and author, who lived and worked in PNG for several years. He is the author of Endurance, a novel based on the life of Frank Hurley, published by Allen & Unwin in 2015. He will shortly hear if his project to celebrate the 50th anniversary is to receive Commonwealth Grant funding.