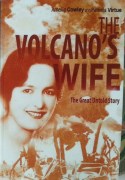

The Volcano’s Wife: The Great Untold Story by Amalia Cowley and Pamela Virtue

Inspiring Publishers, Calwell, ACT, Australia, 2015, ISBN 9781925152951, 208 pages, Paperback, Photographs, maps, index. Category: Memoir/Biography. Available from the PNGAA for $25.00 plus postage.

This absorbing and heart-felt story will appeal to anyone with a soul and a love for Papua New Guinea and its people. It has some harrowing parts—as you might expect from a book about the great human tragedy of the disaster at Mount Lamington volcano on Sunday 21 January 1951—including stories of the survivors who were left with life-long grieving if not psychological trauma. But, make no mistake, the human spirit shines through and your own spirits will lift in reading The Volcano’s Wife through to its conclusion.

This absorbing and heart-felt story will appeal to anyone with a soul and a love for Papua New Guinea and its people. It has some harrowing parts—as you might expect from a book about the great human tragedy of the disaster at Mount Lamington volcano on Sunday 21 January 1951—including stories of the survivors who were left with life-long grieving if not psychological trauma. But, make no mistake, the human spirit shines through and your own spirits will lift in reading The Volcano’s Wife through to its conclusion.

Pamela Virtue, one of the authors, was just 12 years old when a catastrophic and unexpected ‘lateral blast’ from near the top of Lamington volcano swept northwards down over her family’s home at Higaturu, the Australian Administration’s headquarters in the Northern District (now Oro Province) of Papua. The ‘blast’ killed both her father, Cecil Cowley, the Australian District Commissioner at Higaturu, and her 16-year-old brother, Erl. They were just two of the thousands of people who perished in what some people (but not the authors of this book) have called ‘Australia’s greatest natural disaster’: a debateable moniker if ever there was one, given that the great majority of the victims were Melanesian Papuans, and Australia at the time was a governing colonial power of the then Territory of Papua and New Guinea, later to become the Independent State of Papua New Guinea.

Pamela and her mother, Amalia Cowley, survived because on the Saturday night before the eruption they left Higaturu to stay with friends, the Stevens, just outside the area that would be totally devastated by the volcanic blast the following morning. And mother and daughter only just survived the eruption too, as testified by this description on pages 95-96:

The burst from the earth seemed to be coming at a terrific rate, rising higher and higher as it hurtled toward us. The thick black cloud of superheated ash had reached the store where Pam had just been and had engulfed it and the small village. Everyone in it had perished … We all ran for ‘Steve’s’ (Mr Stevens) truck to try to escape the thick ash rolling towards us, but the truck slewed off the road into a ditch … We got down and sat by the truck. We could do nothing but wait to die…

Then, amazingly, the advancing hot ash cloud stopped and, almost miraculously, seemed to reverse its direction of flow! Amalia, Pamela and the other terrified, trapped people were saved from death by a whisker. Mrs Stevens later said ‘It seemed as though the hand of God had turned the might of the satanic forces away from us’. The geophysics of such laterally moving volcanic clouds or flows, however, is now fairly well known. These apparently relentless, hot, ground-hugging clouds eventually lose their energy and forward momentum and can then ‘collapse’ and stop quite suddenly. Next, the buoyant hot volcanic gases and the heated expanded air in the remains of the collapsed flow rise quickly into the air and draw in the ash from below, sucking back what was previously the advancing front of the flow.

The words quoted above were written by Amalia Cowley. Pamela extracted them from her mothers’ unpublished papers. This is just some of Amalia’s material that Pamela has skillfully interwoven into her own well-paced narrative of events between 1900 (when Amalia’s Italian family first came to Australia) and the present. Pamela’s deep respect and love for her mother are enduring themes of the narrative. She always refers to Amalia as Mother whereas Cecil, who was equally loved, is just called Dad!Pamela’s mother, who died in 1998, is indeed given first place in the Cowley and Virtue order of authorship on the front cover of The Volcano’s Wife.

The intensity of the disaster trauma experienced by Pamela in 1951 meant that 52 years were to pass before she could brace herself to return, with her husband Gerry in support, to the killer mountain south of present-day Popondetta, and thus face the childhood memories and nightmares that had haunted her well into adult life. But the experience of returning in 2003, and again in 2004, and accepting the warmth and understanding of the elderly Papuan survivors—who had their own life-long traumas to deal with and still remembered her as the daughter of the well-respected District Commissioner—was cathartic. Ceremonies and shared weeping started the healing of what the reader will soon recognise had been a troubled soul.

The local Papuans gave Pamela the name of Ruja during her visit in 2003. ‘Mount Lamington’ is the European name for the volcano, but the mountain in local Orokaivan culture is associated with the male-ancestor figure or spirit known as Sumbiripa who lives at its summit together with his wife, Ruja. The reader may therefore conclude that Pamela Virtue is the ‘volcano’s wife’ in this book. But there remains some ambiguity about this when you see the design of the front cover. The title of the book, The Volcano’s Wife, overlaps with a wonderful portrait of Amalia as a young woman, giving the strong visual impression that she, rather than her daughter Pamela, could be identified as Ruja. The shared experience of the 1951 disaster and the loss of Cecil and Erl make the closeness of mother and daughter seem indivisible in this book, so the ambiguity is totally understandable and acceptable.

This, then, is an outline of a book that any serious reader of Una Voce cannot afford to miss. Other people, such as Marjorie Kleckham and ex-kiap Des Martin, have given their own valuable accounts of the Lamington tragedy in Una Voce. Pamela Virtue and Amalia Cowley’s book adds marvellously to this still growing body of literature dealing with memories of the Lamington disaster and its aftermath. Read it and, like me, restore your faith in the power of human recovery.

Pamela describes how she swam in the sea before leaving Oro Province at the end of her 2004 visit:

I walked out into the water, complete with hat. Its warmth wrapped itself around me like a mother her child, and I felt cleansed. No more pain. No more fear of the earth. No more terror, no more distress. (page 205).

Wally Johnson, Volcanologist

WHEN COMPLETING THE FORM, PLEASE BE SURE TO HIT “SUBMIT” SO THAT THE DETAILS ARE REGISTERED.