Karo Araua: Maxwell Hayes

The story of Karo Araua, Armed Constabulary (Papua), who was hanged for murder

told by Maxwell R Hayes, Royal PNG Constabulary 1959-1974.

In 1884, the Crown Colony of Queensland annexed a portion of the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and named it British New Guinea. In 1888 it formally became a British possession and was named Papua in 1906 when it became an Australian external territory.

As administrative control was gradually extended along the navigable coastline, there was little penetration into the inland regions. It was obvious that there would have to be a mail service. With the creation of the British New Guinea Armed Constabulary (BNGAC) in 1890, a facility existed to service coastal and interior government stations, plantations, trading stores and missions. BNGAC led by white Assistant Resident Magistrates (ARM) participated in many exploratory patrols into the unexplored interior always encountering hostile native head-hunters, treacherous attacks, cannibal rituals and large primitive groups who had never seen white men or native police before.

With the extension of government influence, inland trading posts and missions were established. In the late 1890s, gold miners had established a track leading to the Yodda-Kokoda gold fields which produced a lucrative source of gold. The earliest inland government station was established at Kokoda, some 96 km inland from Port Moresby, around the turn of the century staffed by an ARM and armed native police.

In December 1904, a regular weekly overland police mail-runner service commenced to Kokoda government station. Travelling in pairs, the armed native police carrying the mail in a strong leather satchel proceeded bare-footed foot from Port Moresby at sea level in arduous tropical conditions with rain falling on most days through the lowest point at about 3,750m in the Owen Stanley ranges down to Kokoda station situated at about 950m on a plateau. High altitudes in the tropics can be near freezing at night.

Outside Port Moresby the track, later to be known as the Kokoda track, was not one continuous pathway but a series of ill-defined lesser tortuous paths often of single-file width. They were largely for contact with various villages along the route and had existed since time immemorial mainly for inter village trading, internecine warring and headhunting raids.

There were rudimentary rest huts spaced a day’s walk apart. The journey to Kokoda usually took five to six days, with the return trip taking a little less. Some time later the mail run was extended from Kokoda and continued down to the north coast government station of Buna, a distance of some 160km from Port Moresby, a very arduous journey of some nine to ten days in total. There they would be relieved and another team would make the return journey. Over the years several policemen making this journey were murdered when carrying the mail and punitive government patrols retaliated.

Enter a tall Police Motu (the lingua franca of Papua) and village language speaking Papuan from the Gulf region named Karo Araua, born about 1902/03. Government officials in the course of patrols in this area noted that Karo, as he grew older, was rebellious and resented authority, particularly from his parents and traditional tribal elders. None the less at some stage around the early 1920s he was appointed as an unarmed Village Constable (a prominent village native having limited authority in matters of law and order). This seemed to appeal to Karo and around 1926 he used tribal influence to be appointed to the Armed Constabulary (variously known as the Papuan Armed Constabulary and Armed Native Constabulary). He signed an indenture for three years and performed patrol duties in the Central District and in 1928 was appointed to the prestigious position of carrying and escorting the overland mail from Port Moresby to Buna.

Enter a tall Police Motu (the lingua franca of Papua) and village language speaking Papuan from the Gulf region named Karo Araua, born about 1902/03. Government officials in the course of patrols in this area noted that Karo, as he grew older, was rebellious and resented authority, particularly from his parents and traditional tribal elders. None the less at some stage around the early 1920s he was appointed as an unarmed Village Constable (a prominent village native having limited authority in matters of law and order). This seemed to appeal to Karo and around 1926 he used tribal influence to be appointed to the Armed Constabulary (variously known as the Papuan Armed Constabulary and Armed Native Constabulary). He signed an indenture for three years and performed patrol duties in the Central District and in 1928 was appointed to the prestigious position of carrying and escorting the overland mail from Port Moresby to Buna.

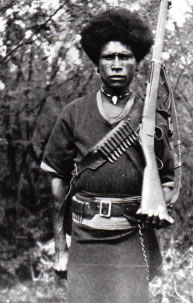

On 5 September 1929, Constable Karo in company with Constable Bili set out from Port Moresby. Their equipment consisted of a Martini-Enfield rifle, bayonet in scabbard, a cartridge belt, ammunition, a long brass chain (which served as a primitive handcuff until 1964), spare uniform, a carrying bag with biscuits, rice, tins of meat, coconut meal and sticks of native tobacco for trading for fresh meat and fruit obtained along the track. They would space a day’s travel to camp overnight at a government rest hut, if possible.

At one such rest hut an argument ensued between Karo and the older Bili. He accused Bili of not carrying his fair share of the heavy leather mail satchel. Bili refused; Karo shot him in the back and rolled his body off the track. He then proceeded alone to Kokoda. On arrival he informed the ARM of what had occurred, a search was made for the body, Karo was arrested and returned to Port Moresby in handcuffs. Here the murder was investigated by the European Constable, Tom Gough1 who had arrived only a few months earlier. Believing that he had a just

reason, Karo made full admissions of the murder and was confined in the Badili (also known as Koki) native prison. He was committed for trial and appeared in the Central Court in November. He was charged with wilful murder under the provisions of Section 302 of the Queensland Criminal Code 18992. Owing to leniency shown to natives due to tribal customs by the administering Australian Government, the charge was reduced to manslaughter under Section 303. He was sentenced to 5 years in hard labour and after serving about four years and nine months he was returned to his Gulf village.

In September 1935, Karo and some fellow villagers were questioned on suspicion of breaking into a trade store east of Port Moresby and taken to the coastal government station of Rigo. Here he was charged with some minor offences and fined in late October. On 12 November the safe in the office at the government station was stolen. No other government safe had ever been stolen in the history of this territory; such a crime was unthinkable. The safe was later found, broken open in a creek bed

with a large sum of money in notes and coin missing. Suspicion centered on Karo and other villagers.

When news of this crime reached Port Moresby, Sergeant Bagita3, the constabulary’s ablest investigator was sent to Rigo. He spoke several of the local Papuan languages as well as Police Motu. Meanwhile in the capital, Port Moresby Constable Gough was making extensive and widespread enquiries for local natives in possession of large sums of money. A co-conspirator eventually led Bagita to where some of the money had been hidden, confessed to the crime and named Karo as the principal offender. On 21 January 1936, Karo was brought before a magistrate and sent back by government trawler to Port Moresby where he again faced Constable Gough.

After committal, Karo faced the Central Court charged under Sections 398 (stealing) and 421 (burglary) of the QCC and was sentenced to 10 years with hard labour at Koki prison. Proving himself to be a recalcitrant while on a town working party in February he escaped. He was arrested a few days later by Bagita, subjected to strict discipline, and transferred to the most distant prison on the island of Samarai.

Feigning blindness (self-inflicted by rubbing a native plant into his eyes), he was returned to Koki prison for treatment. Here, as he was apparently blinded, he did no hard labour but embarked on schemes to make money by gambling, sleight of hand and sorcery.

As with most prisons, there is a hierarchy of prisoners and Karo quickly established his position at the top. He had the virtual run of the whole prison and, being generally believed to have magical powers, had considerable influence over junior warders extending to the senior warder, Sergeant Ume Hau. Ume was an inveterate gambler though gambling was strictly prohibited by Papuan law. Amongst the prison staff and the prisoners, due to tribal loyalties and languages, there was almost always some distant shadowy relationship by way of trading or marriage involved. There also existed an obligation to accommodate other villagers, and debts had to be repaid.

Around May 1938, fellow prisoners were well aware that there was considerable tension between senior warder Ume and prisoner Karo. Cell keys were lost and Karo’s confinement at night a matter of carelessness. Not being a Motuan language speaker, European Gaoler George Gough4 was almost certainly unaware of the undercurrent existing between Ume and Karo and of their close relationship. He would have known little of the widespread belief in the powers of sorcery (puri puri) or of the fear under which many Papuans lived.

The last time Sergeant Warder Ume was seen alive was after the evening meal on Monday 6 June. At the Tuesday morning prisoner inspection line-up Ume was absent. Believing that Ume may have absented himself from duty and together with his wife Boio and their adopted daughter Igua, aged about twelve years, left the prison for family, gambling or trading reasons, Gaoler Gough had a search made of the native prison area and environs without success. Constable Gough extended the search to Ume’s village and beyond also without success.

The search continued until late on the afternoon of Wednesday 8 June, when the humid tropical climate revealed the decomposing presence under the rarely used European section of the prison of three bodies all with their throats cut. Suspicion quickly centered on Karo and after extensive questioning of other Papuan prisoners who implicated Karo and the finding of blood stained clothing and knives by Constable Gough and Sergeant Bagita, Karo and a co-conspirator named Goave Oae were arrested.

Other prisoners had implicated Goave (who was serving life for a 1931 murder) in handing Karo a knife during the evening of the Monday night murders. Karo made an admission of guilt to Bagita and both offenders were charged with wilful murder. They were committed for trial in July and sent for trial before a Judge alone, as was the law for Papuans.

After the trial, which concluded in the Central Court on 18 July, Karo was found guilty of wilful murder and sentenced to death. The lesser conspirator, Goave, was acquitted and returned to prison to continue his life sentence. Neither was charged with the murder of Ume’s wife and child.

Since Karo’s earlier murder when a police mailman and his earlier imprisonment on a lesser charge, there had been a change of Australian government and Karo’s fate was sealed. The death penalty was confirmed by the Papuan Executive Council and five days later, on 8 August, Karo, also suspected of several other village murders, was executed outside the Koki prison behind a high hessian structure of the enclosed gallows before a large crowd of Europeans and Papuans, an armed guard of the Constabulary, the brothers Gough, a Catholic priest, a medical officer, Sergeant Bagita and the acting Sheriff to whom the duty as executioner fell.

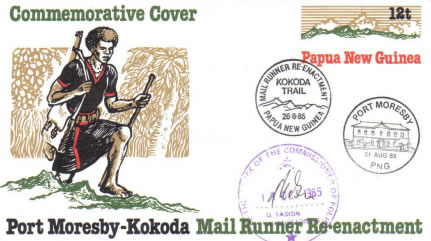

From the early years, police were extensively involved in the carriage of mails throughout the then separate territories of Papua and New Guinea until early 1942. Police runners carried mail from Port Moresby to Kokoda, with the exception of the war years, until October 1949 when Qantas commenced weekly air services. Post-war extensive routes were traversed elsewhere in most parts of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea and continued in Bougainville until at least 1956. These ‘police runner’ catcheted covers are now very scarce philatelic items.

Mail re-enactment cover depicting a police mail runner

Photo: Hayes Collection

On 26 August 1985, the centenary of postal services in Papua was commemorated by the re-enactment of a police mail run from Kokoda. At the top of the Kokoda track, a specially issued pre-stamped commemorative cover was cancelled on that date. Covers were conveyed on foot back to Port Moresby by a party of seven Papuan New Guineans under the command of Sergeant Peter Baiagau of the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary. After the five day trek the covers were again cancelled at the Port Moresby post office on 31 August.

Karo’s execution was only the second in Papua since 1916 and was the last in Papua before the acts of World War 2 were dealt with in later war crimes trials. On 15 January 1934, former Sergeant Stephen Mamademi Gorumbaru of the Armed Constabulary, with fifteen years’ service and serving at police headquarters, was convicted of the rape of a European female child. He was hanged at Badili prison, Port Moresby on Monday 29 January.

Compiled from personal conversations with Sgt Major Bagita, recollections from other long serving native police, notes from Rita O’Neil (daughter of TP Gough), assistance from Rick Giddings, a former long serving district officer and magistrate, and from Karo, the life and fate of a Papuan, Amirah Inglis, ANU, 1982, to whom I extend my thanks.

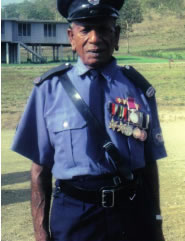

Bagita wearing the pre-war 4 stripes with

coat of arms Port Moresby 1960. Photo: MR Hayes

Bagita, wearing his newly presented BEM on his

retirement parade at Bomana Police College, 1966

(Hayes collection)

This photo was published in People in 1950 and wrongly entitled ‘Karo and co-accused Goave on their way to execution’. This is incorrect. Karo was hanged and Goave continued to serve his life sentence. The correct title would be ‘Karo and Goave on their way to trial in Port Moresby Central Court.’ The detail is obviously of Karo. Photo from Rita Gough (Tom Gough’s daughter).

NOTES

1. Thomas Patrick Gough, born 15 June 1893 Rosevale, Qld. Served in the Queensland Police between 12 March 1914 and 15 September 1920. Appointed to Papua 4 May 1929 and served until 14 February 1942 (suspension of civil administration in Papua WW2). He was the second European Constable appointed in Papua. He was reappointed post-war on 8 October 1945 to RPC&NGPF, and retired as Superintendent on 26 November 1951.

2. The Queensland Criminal Code 1899, (as amended) remained the principal statute law of Papua until 1942, and subsequently post-war for both jointly administered Territories of Papua and New Guinea until 1975.

3. Bagita Aromau, BEM, QPLS&GC Medal, of Ferguson Island, born about 1900, joined the Armed Constabulary in 1916, and retired at a full dress parade at Bomana Police College at the rank of Sergeant (First Class) [though he was always entitled the more prestigious title of Sergeant Major] in 1966. He served continuously with three years’ war service in the Royal Papuan Constabulary for fifty years. He died in Port Moresby in October 1973. He remains the longest serving native or European police officer of Papua New Guinea. There will never be an equal in Bagita who proudly wore five stars beneath his war medals, one for each ten years of loyal and distinguished service. I am proud to have known and served with him.

4. George Andrew Gough, born 9 April 1907, Rosevale. Originally came to Papua as an agricultural worker on a coffee plantation leading to becoming the manager of the prison gardens and the appointment of European Gaoler on 8 October 1936, He served until 14 February 1942 and was reappointed to RPC&NGPF 2 January 1946. He retired as Superintendent, Corrective Institutions on 30 June 1962.